Jacques Joseph Tissot was born in Nantes in October 1836, France to a fervent Catholic family. His father, Marcel Théodore Tissot, was a successful drapery merchant and his mother, Marie Durand, was a designer of hats. Marie instilled in her son a pious devotion to her Catholic faith. Jacques spent his youth in Nantes, and many of his later paintings contained river scenes and the shipping that he would have seen working up and down the River Loire. His father was adamant that Jacques would follow him in the family business, but by the time he was 17 the boy knew that he wanted to be a painter. His mother supported him in his choice of career, and Jacques decided that he would change his forename to the more anglicised James.

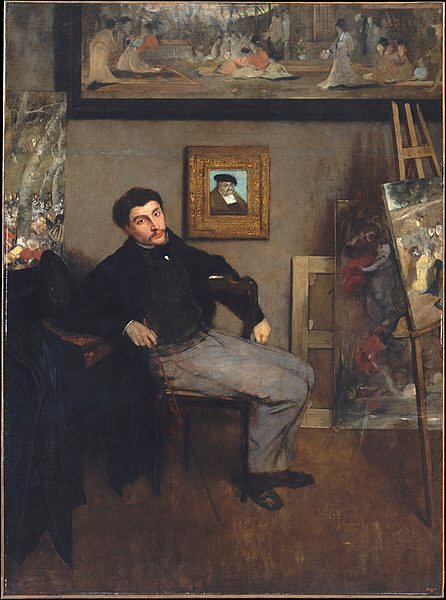

In 1856 or 1857, Tissot travelled to Paris to enrol at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts to study in the studios of Hippolyte Flandrin and Louis Lamothe whilst lodging with a friend of his mother, painter Elie Delaunay. Around this time James began meeting other influential artists of the day, the American James McNeill Whistler, and French painter Edgar Degas who was studying in the same school along with Édouard Manet. His first exhibition was in the Paris Salon in 1859 during which he displayed five paintings. Success for James came a year later when the French government paid 5,000 francs for The Meeting of Faust and Marguerite, which he again exhibited the following year along with other paintings. Fellow artists, Claude Monet and Alfred Stevens were exploring Japanese art, and James also dabbled with the theme for a while before returning to his more familiar subjects. It was during this period that his friend, Degas, painted James’ portrait working in his studio.

Degas' portrait of James now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

He became an international artist when he exhibited in the 1862 international exhibition in London at the gallery of Ernest Gambart and James sensed that if he changed his approach he would be more successful. He began to accept commissions for portraits and scenes depicting contemporary life and was rewarded with critical acclaim.

Un dejuner, 1836

Un dejuner, 1836

Things were going well for James until the States of the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia decided to invade France in 1870. The war lasted seven months, from July 1870 to 28 January 1871. The Germans defeated the French armies in northern France and surrounded Paris, which fell on 28 January 1871, and just two months into the war, the French formed a new government for national defence and fought on. James was living in Paris, and when the Germans took the city, the Parisians formed a revolutionary group called the Paris Commune, which seized power and held the Germans at bay for two months. Tissot joined the Garde Nationale and fought with them on the barricades, more to protect his own belongings from looters than fighting for an ideal. The commune was bloodily suppressed by the regular French army at the end of May 1871, and having seen enough of war Tissot packed his bags, gathered his belongings, and sailed for London.

He had enough money to buy a house in St John’s wood, and found that his good reputation had preceded him. He had already worked as a caricaturist for Thomas Gibson Bowles, the owner of the Vanity Fair and he resumed his work for the magazine using the pen-name Coïdé. He gained admission to the Arts Club of London and Invitations to exhibit at the Royal Academy soon followed. By 1874, one jealous critic wrote sarcastically that he had “a studio with a waiting room where, at all times, there is iced champagne at the disposal of visitors”. In 1874 his old friend Degas asked him to return to France and join a new movement of painters who called themselves the Impressionists. Tissot declined, though he never lost contact with his old friends, and travelled to Venice with Édouard Manet and regularly saw Whistler, who influenced his Thames river scenes.

His decision to remain in England brought James his greatest reward when in 1875 he met a young divorcee called Kathleen Newton. She moved into his house in St. John’s Wood in 1876 and gave birth to a boy, Cecil George Newton. She lived with James for the next six years before she died of consumption in 1882. In the years that followed, James always referred to his time with Kathleen as the happiest days of his life. Despite all the acclaim for his art and the money that he had earned, nothing could replace the love of Kathleen and the family that he had briefly found.

James' portrait of Kathleen

James' portrait of Kathleen

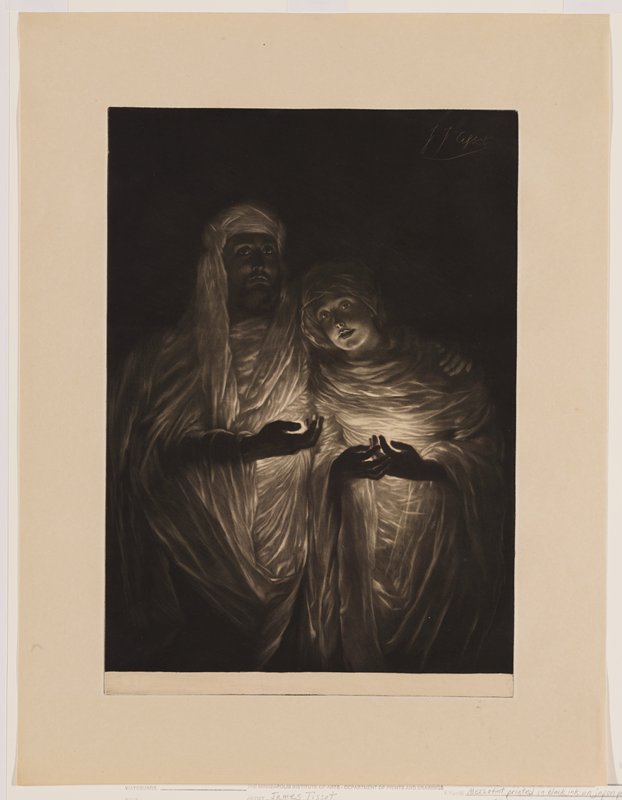

The loss of Kathleen led to a profound change to James’ life. There is a little known painting of his that had been assumed destroyed or lost for decades. It is now in Tissot’s collection of photographs and paintings in his studio in the rural Bouillon region of southern France. It’s called The Apparition. After her death he visited several spiritualists, but the dark painting shows the well-known spiritualist and medium, William Eglinton, accompanied by a woman. Both are shrouded in white and holding orbs of light. It is supposedly based on a vision Tissot had in a séance with Eglinton.

Shortly after Kathleen’s death Tissot returned to France, but he was not the same man who left a few years earlier. When all of France was buzzing with Impressionism, James changed to watercolours and he began painting biblical pictures. Some have argued that he took advantage of a growing movement of Catholic revival, but his conviction to his new theme was strong enough for him to visit the lands of the Bible. Between the years of 1886 and 1896 he travelled to the Middle East three times to make sketches of the people and towns. His watercolours, always well researched, moved towards realism and accuracy of detail. He produced a series of 365 gouache watercolours which he exhibited in France in 1894/5, London 1896 and New York in 1898/9. In 1900 the Brooklyn Museum bought the collection and published them in two versions; one in French and the other in English. After the first exhibition in France in 1895 Tissot was awarded the Légion d'honneur, France's most prestigious medal. James carried on painting subjects from the Old Testament and exhibited 80 of them in Paris in 1901.

Tissot's illustrations for sale on the internet, second hand at £3,760. Published by M. de Brunoff & Cie, Paris, 1904

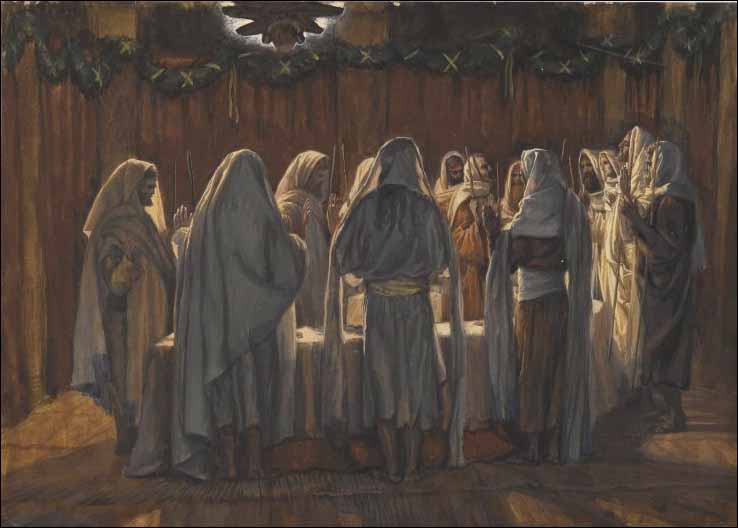

One of the gouache paintings that he painted was the Last Supper. If you remember the Agape Feast drawings in the catacombs of Rome, the people at the table were laying down on beds. This is what Tissot saw for himself on his visits and accurately drew in his pictures. The table is sparse, but the symbolic Holy Grail is placed in front of Jesus. He painted another picture whose theme is less familiar, but will show up again later on. It shows the disciples standing in a circle with Jesus on the right apparently blessing them. Both paintings convey an air of sadness and knowledge of the horrors to come.

That could be the end of the story, but there’s more.

Tissot’s depictions of the Holy Land had a historical value, and when film director William Wyler began a remake of the 1925 silent film Ben Hur in 1959 he began looking around for authentic biblical scenes. His researchers showed him Tissot’s drawings and he used many of them for his scenes, especially What our Lord Saw from the Cross.

When George Lucas was writing The Raiders of the Lost Ark in the 1970’s he had to ask what the Ark of the Covenant actually looked like. He was shown Tissot’s Moses and Joshua in the Tabernacle and The Ark Passes over the Jorden and when the time came for making props he ordered copies of Tissot’s ark to be made for filming.

Just to add a topical note. The Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion in northern Ethiopia is the reputed resting place of the real Ark of the Covenant. According to the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, it was taken there by the Queen of Sheba’s son Menelik and King Solomon of Israel after Jerusalem was sacked in 596/587 and Solomon’s temple destroyed. It has been guarded by monks who are forbidden to leave the church grounds until death. The war that is going on there is putting the ark in danger. Eritrean troops have been looting churches in the area and reports of mass shootings of civilians and photographs of damage to the church are emerging. I write theses blogs sometimes weeks in advance, so by the time you read this there may be more news.