Joseph Harry Anderson was born on August 11, 1906. His family were devout Seventh-day Adventists and his father, Joseph, named all of his son’s Joseph, so each son went by his middle name, and this is the name that Harry used throughout his life. Harry had a sister and two brothers and all of them were outstanding students, with Harry excelling in mathematics.

His aim was to study maths at university, but in the interval between college and university Harry worked as a stock boy in large stationary store. When the store sign painter could not meet his deadlines Harry offered to stand in. His manager found Harry to be more than satisfactory, and he let him use a fourth floor room as a studio and he became the store’s permanent sign painter.

He enrolled at the University of Illinois in 1925, but when he came to register for his sophomore year he had to choose another subject. The maths course was hard work and Harry wanted something easy that would not overtax him. He chose a course in still life painting. After his first year in the art classes, his teacher, who was an alumnus of the Syracuse School of Art, asked him if he had considered art as a profession rather than mathematics. In the autumn of 1927, he began attending classes at Syracuse as a full-fledged art student with friend and fellow artist Tom Lovell.

The two attended classes together and shared a studio in the attic of Anderson’s dormitory. As well as working on course subjects, they earned extra money freelancing with Harry working on lettering jobs and Tom painting pulp covers. They both graduated with honours in 1931and moved to New York City to set up a studio in some old stables in McDougall’s Alley just off Washington Square. They had arrived in the illustration world in the middle of the depression and work was very hard to find. Harry served behind the counter for a sweets store in the evenings, and by day toured the agencies with his portfolio of artwork. Finally, after months of small jobs producing book jackets, he got his first commission from one of the big magazines, Collier’s.

With Collier’s under his belt was more confident about approaching the big publishers and agencies and began to earn enough to support himself with art alone. He quit the sweet store and paid off his debts, but he was tired of the rat-race in New York and began to save for his fare to return to Chicago where he knew the biggest prize was.

The Stevens-Gross Art Agency was the most successful art service agency in the Midwest, if not the entire country. They had a studio room where all their artists worked together and had models and photographers working along with the artists. Reps toured the country and brought in orders from advertisers and the top magazines in America. For providing this service, Stevens-Gross took 50% of sales, but Harry thrived on it.

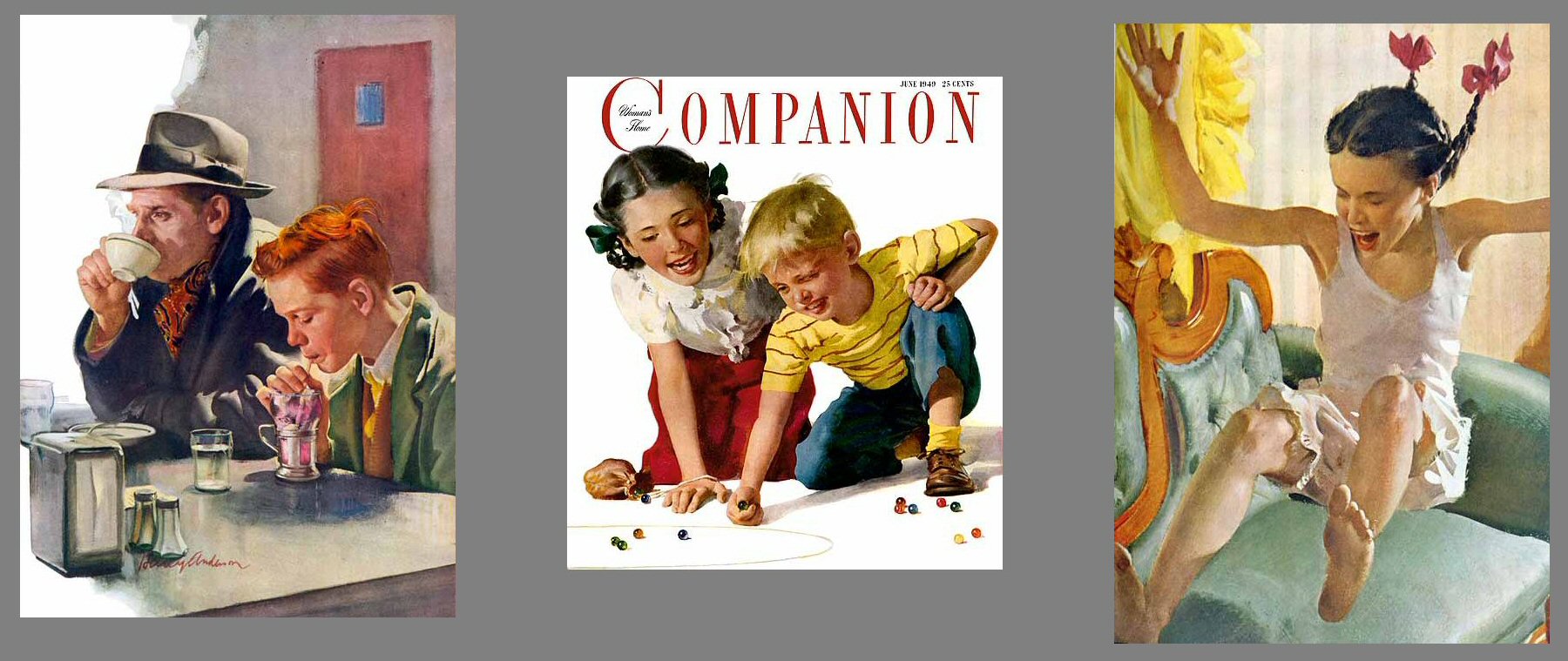

His first big assignment was a series of illustrations for a Cream of Wheat advertising campaign, produced in 1937. Big commissions began to come to him: American Airlines, Ovaltine and Ford all asked for Harry to paint their advertisements. By 1940 he was working for Collier’s, Redbook, The Saturday Evening Post, Woman’s Home Companion, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Cosmopolitan.

Cosmopolitan, Woman’s Home Companion, Cosmopolitan.

Esso, Coca Cola, Colliers.

It was whilst he was working for Stevens-Gross that he met a young woman called Ruth Huebel who was working as a model in the studio room. They dated for a while during 1940 and finally married. It is Ruth who modelled as the mother comforting her young daughter in the Collier’s painting above. Harry had kept his faith throughout the years and he and Ruth joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Harry was now very well established in his own right and could leave Stevens-Gross and work for the Haddon Sundblom studio. Shortly after this move he had a crisis of faith. He felt that, due to his religious beliefs, he could no longer continue to paint for some of the publishers or companies that he had been working for in the past. The decision would have a big impact on his income.

By 1944 Harry and Ruth had two boys and a daughter to look after, and were struggling financially. Because of his strong beliefs and his fame as an artist, Harry was approached by The Review and Herald Publishing Association to produce religious illustrations for them. Harry agreed, and his first commission for the church was to paint Jesus talking with children. He broke with the long traditions of the publishers to show Jesus in a modern setting rather than a biblical one. He painted Jesus in a garden with a young girl dressed in modern clothes sat on his knee. There are other modern children around him and the girl on his knee is asking about the crucifixion marks on his hand. Harry called the picture What happened to your hand? The painting caused a furore within the church, and the editor was urged not to print it because it was blasphemous. He was on the verge of returning Harry’s work when the editor’s daughter saw the picture and said that she wished she could sit on Jesus’ knee and hold his hand. That made up the editor’s mind. He printed the picture, and instead of the predicted disapproval, it was met with great acclaim. Harry continued with his modern theme and produced around 300 religious illustrations for the Review and Herald Publishing Association over the next 35 years. Eventually, this huge body of work comprised half of the total artistic output of Harry’s life. He continued to paint commercial art, but he split his time between that and work for the church. Throughout the rest of his career he charged only the minimum wage for his religious artwork.

In 1946, the Andersons moved to Washington. D.C. to be closer to The Review and Herald offices. He continued working for several of his old customers and in 1949 he painted covers for a whole year’s editions of Woman’s Home Companion. The theme for each cover was “brother and sister” and Harry’s own son was model for some of them, but Harry was beginning to feel a little isolated and missed the interaction with other illustrators that he had enjoyed over the years. Finally, in I951, the Andersons moved closer to the New York City area. During this period, Anderson began to receive awards from several of the associations that he had worked for, and he was featured in a 1956 issue of American Artist in recognition for his contribution to art.

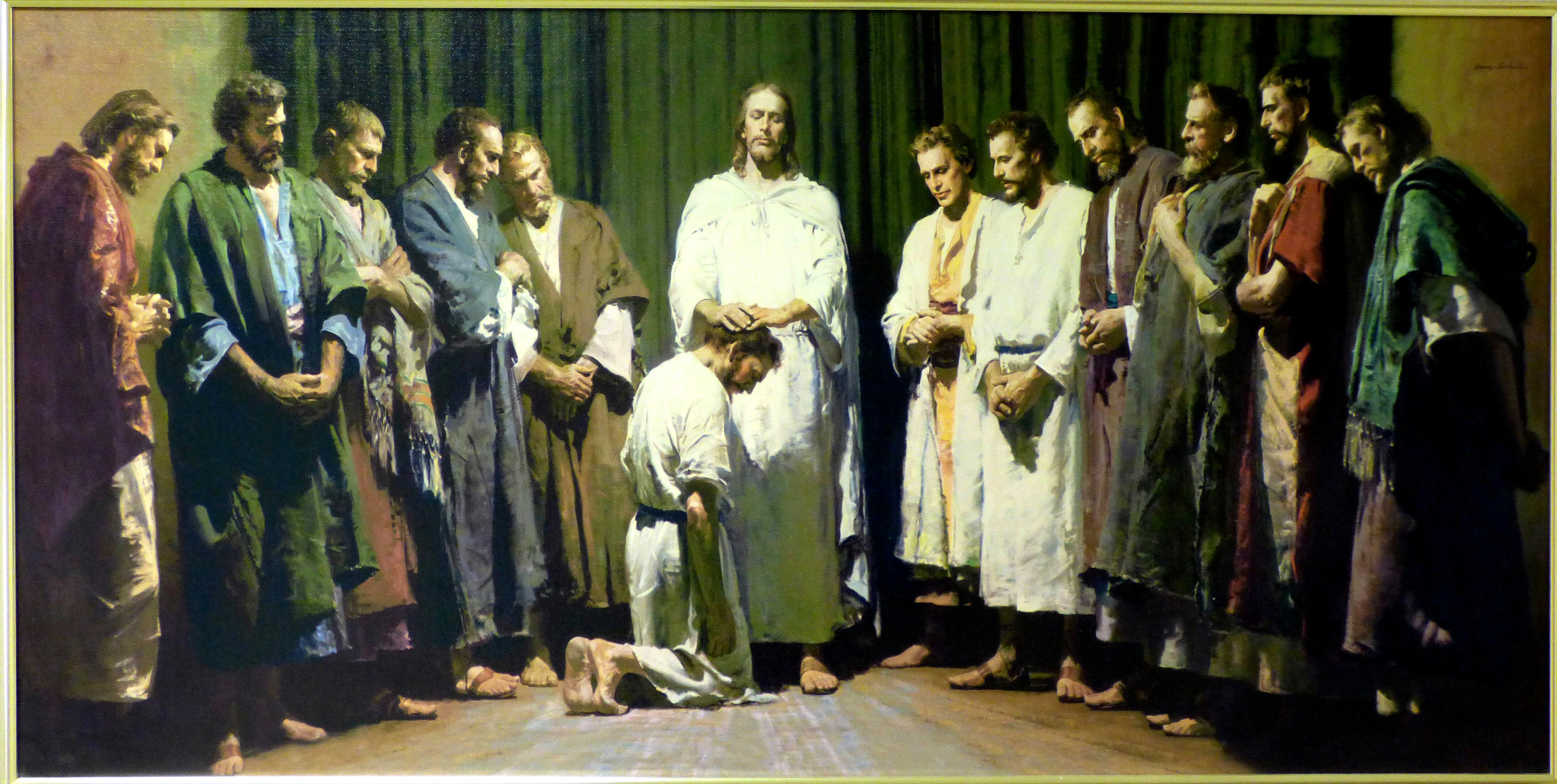

In the mid 60’s he was asked to paint a number of paintings for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. For the church’s pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair he painted a large mural in oils of Jesus ordaining his apostles. Re-prints of this painting can be found hanging in nearly every Latter-day Saints Church meetinghouse and temple in the world, following this, he did nearly two dozen more paintings for the LDS Church and his paintings are also still widely used by the church for many of its printed and online materials.

I have seen a large print of The Apostles close up, and I can verify the detail and accuracy of skin colours and the textures of the clothes. This is, to my mind, his crowning masterpiece. Harry continued painting at this level for several more years, and because of his fame, his work was exhibited in the most prestigious and visible venues. But technology was overtaking him. From the 70’s onwards, photography had become the preferred medium for advertising. Harry carried on painting for Esso (later Exxon), Humble Oil, John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company and Redbook. He also continued his devotion and professional relationship with the Seventh Day Adventist Church and the Review and Herald. By now, Harry was in his eighties and painted just for enjoyment.

In recognition for the 70 years of his professional life, he received the Grumbacher Purchase Prize from the American Watercolour Society, the Clara Obrig Prize from the National Academy of Design, and numerous awards from the Art Directors Club. Additionally, he was elected to the Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1994. Harry died in 1996, aged 90.

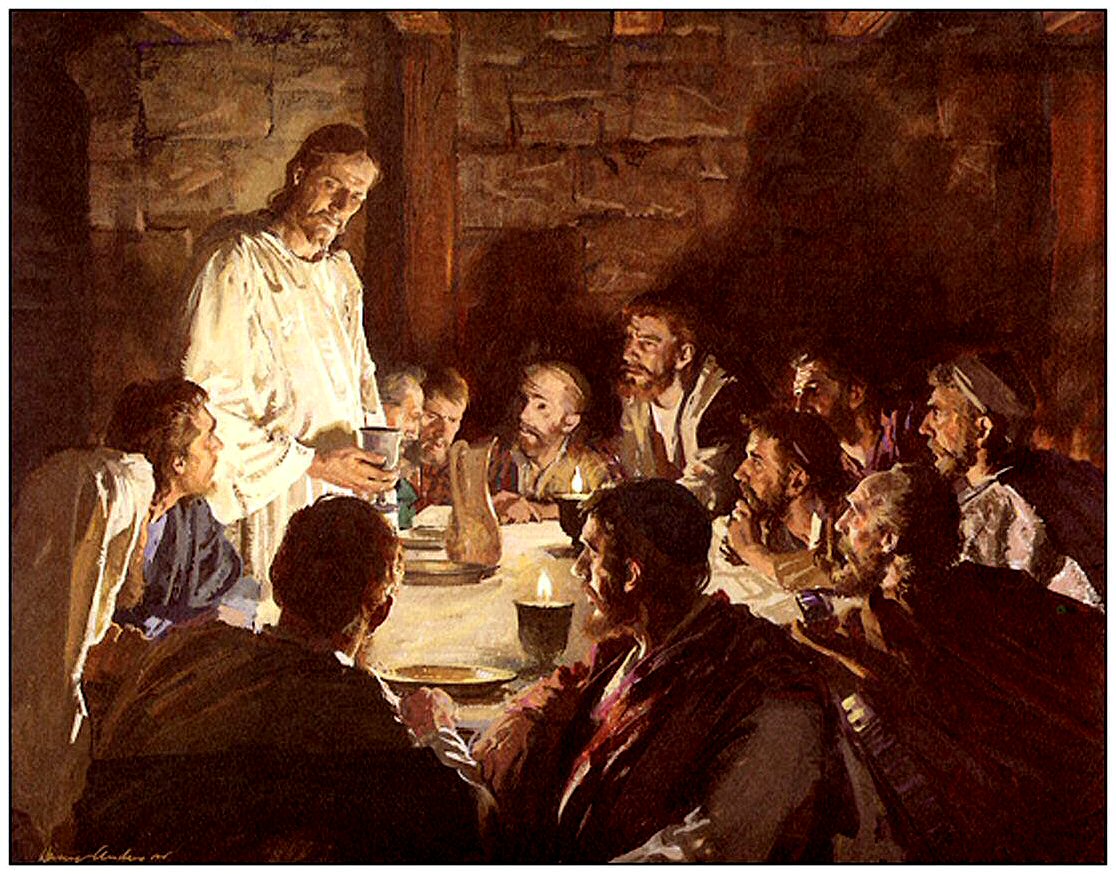

But where’s the Last Supper? Well, this is Harry’s Last Supper, and it’s the most believable last supper of them all. There is no huge table as Da Vinci painted, or the great feast with half a dozen servants as Tintoretto painted, and nobody bought a place at this table. Harry was meticulous about detail, and he painted what he thought that meeting so long ago in one of the poorer houses of Jerusalem would have looked like. The dress of the disciples is that of men who have wandered from town to town following Jesus as he preached. They all eat frugally, and now Jesus tells them that he will be betrayed in the morning and must die soon. The photograph here is poor, but the painting is up to Harry’s high standards and is beautifully done.

We’re nearly at the end of the last suppers. I have missed out half a dozen worthy of mention. In fact, there are hundreds more Last Suppers, but they would have become tedious.

There is only one more Last Supper left, and I know that you will enjoy it.