The big mistake

Friday, October 29, 2021

Columbus was 41 when he was granted the funding to find a route to the orient, though he had spent about ten years touting his theory to every monarch and financial backer in Europe. He was experienced in sailing and navigation and was a member of a small group of sailors who had explored the oceans. He was born in 1451 in Genoa, and initially spoke a dialect of Ligurian as his first language, though he never used it in any of his later documents or letters. His father was Domenico Colombo, a wool weaver, who worked both in Genoa and Savona and his mother was Susanna Fontanarossa. He had three brothers: Bartolomeo, Giovanni and Giacomo, as well as a sister named Bianchinetta.

In 1470, the Columbus family moved to Savona, on the coast to the west of Genoa, where his father took over a tavern. The same year, Christopher, aged 17, sailed on a Genoese ship hired in the service of René of Anjou to support his attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples. Three years later, he began his training as business agent for the important Centurione, Di Negro and Spinola families of Genoa, and in May 1476 young Columbus took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry valuable cargo to northern Europe. He probably docked in Bristol, England, and Galway, Ireland. He boasted in his diaries much later that he visited Iceland in 1477, but what is known for sure is that he arrived in Lisbon that same year to join his brother Bartolomeo who worked in a cartography office.

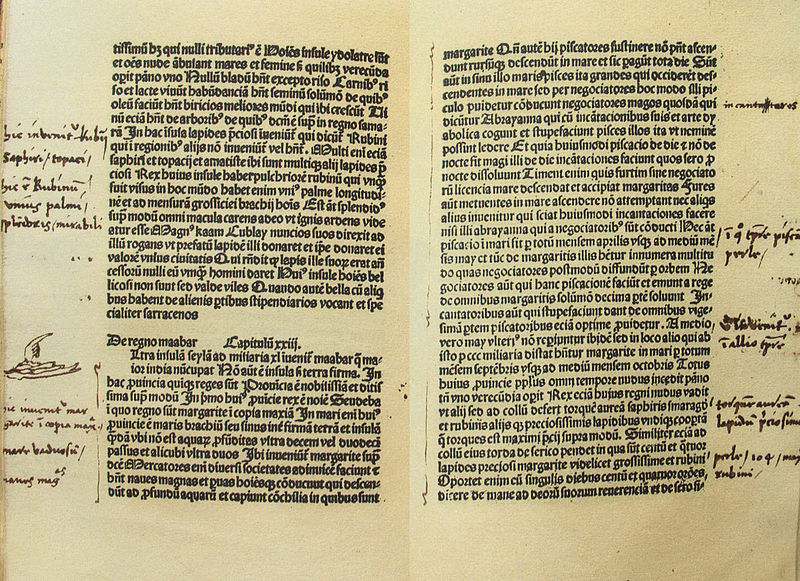

It was in Lisbon that he set up home and married Filipa Moniz Perestrelo, daughter of the governor of Porto Santo. Two years later, his first son, Diego Columbus, was born. Christopher was not an academic, yet he learned to read and write in Latin, Portuguese, and Castilian. His reading covered books about astronomy, geography and history and included an impressive list of authors: most of the scientific writings and maps of Claudius Ptolemy, Pliny’s Natural History, Cardinal Pierre d'Ailly’s Imago Mundi, Pope Pius II’s Historia Rerum Ubique Gestarum, The travels of Marco Polo, and The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. We know this because his books were preserved and handed down and we can read the copious notes that Columbus wrote in the margins.

Columbus' notes in the book by Marco Polo.

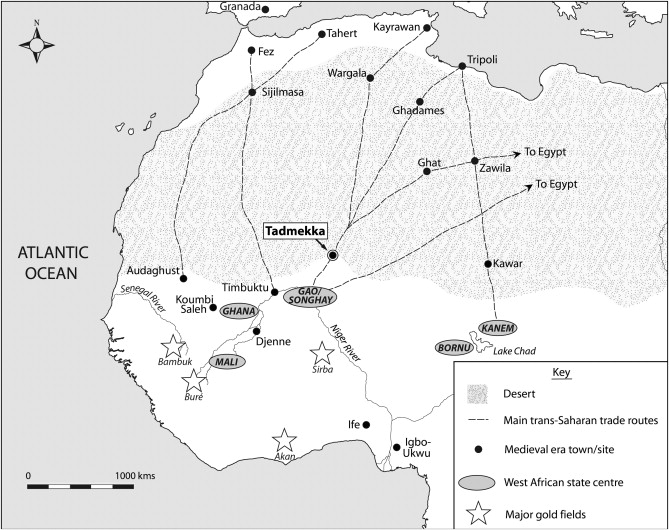

This was a difficult time for traders like Columbus. The Mongol Turks had allowed the free passage of trade goods overland via the Silk Road for centuries, but when the Ottoman Turks captured Constantinople in 1453, the land route to Asia was closed to Christian traders, and Portuguese navigators tried to find a sea route to Asia.

Toscanelli Toscanelli

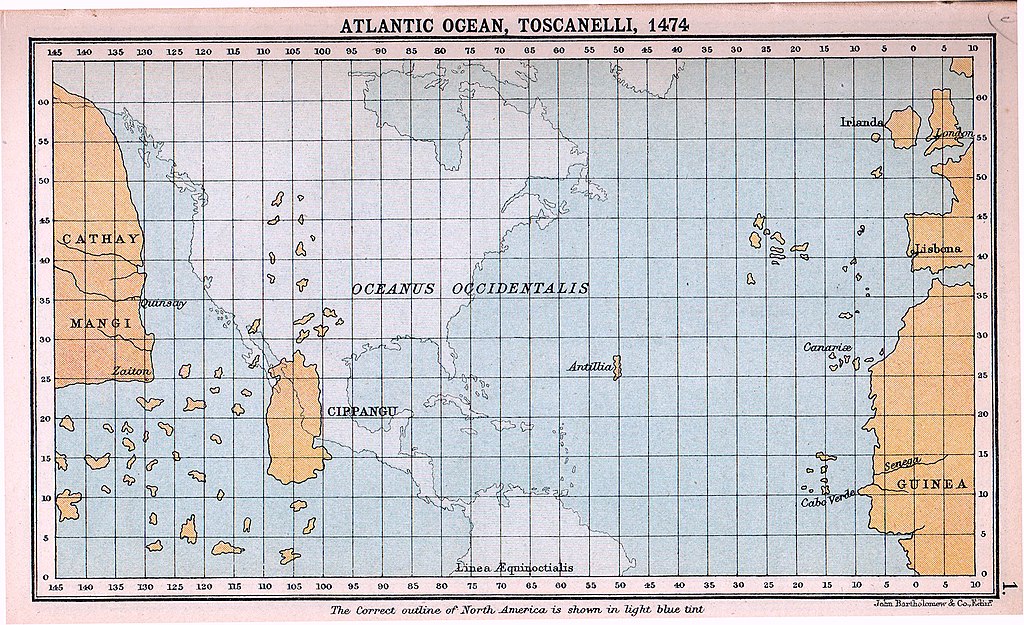

As early as 1470 the Florentine astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli suggested to King Afonso V of Portugal that sailing west across the Atlantic would be a quicker way to reach the Spice Islands, Cathay (Cina), and Cipangu (Japan) than the route around Africa, but King Afonso rejected his idea.

Columbus and his brother learned of this and made some enquiries which led to Toscanelli sending the Columbus brothers a map in 1481 showing that a westward route to Asia was possible. In the meantime, however, the king encouraged mariners to find another route to Asia by going south, rounding the Cape of Good Hope and passing into the Indian Ocean. In 1488, this is exactly what another navigator, Bartolomeu Dias, did. This took the wind out of the Columbus boys’ sails.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Columbus was employed as a trader, and he was obliged to spend months away at sea. Much of Portugal’s trade was with Africa, and he traded along the Guinea Coast from the trading station of Elmina. Sometime before 1484 he called at Porto Santo in the Madeira Islands where he learned that his wife had died, and that he must return home to take care of his son. With his wife’s estate settled, Columbus and his son left for Córdoba, a centre for many of the Genoese traders and the city where Isabel and Ferdinand has set up their campaign headquarters for the war against the Caliphate of Granada. It was here that he met a 20-year old orphan named Beatriz Enríquez de Arana and took her as his mistress in 1487. The next year, Beatriz gave birth to a son by Columbus, whom they called Fernando, after the King of Aragon.

When King Afonso of Portugal turned down Columbus’ offer to find a new route to Asia across the Atlantic Ocean he had consulted some of the best cartographers and sailors of the time, who in turn had studied maps made by the best thinkers and most learned men of antiquity.

Around 250 BC Eratosthenes had calculated the diameter of the earth with his famous experiment measuring the shadow of a pole of a given length in two different places. He obtained a figure of 252,000 stadia, or 24,662 miles. (actual 24,902 miles.) Five hundred years later, Ptolemy, the author of the Almagest star chart, and giant amongst the philosopher/scientists of antiquity, had drawn a map of the known world. He estimated that the entire Eurasian continent from Portugal to the Chinese coast spanned 180 degrees of longitude. This map had been part of a three volume encyclopaedia on geography which had been translated from Greek into Arabic sometime in the ninth century. The books disappeared in time, but the map was copied by Byzantine monks and published in 1295. The map had been widely reproduced in 1486 and was available to European mariners, whose voyages were filling in the blank spaces around the edges. The most important aspect about the chart was that, as with star charts, he had drawn in meridians which were the first attempt at using latitude and longitude. (Ptolemy was the chief librarian at the library of Alexandria and had access to written information going back centuries.)

Ptolomy's Mapa del Mundo: photo: Francesco di Antonio del Chierico.

If Eratosthene’s circumference for the earth is divided by 360, this will give the length of one degree of longitude at the equator. According to Ptolemy, the whole Eurasian continent spanned 180 degrees, that left another 180 degrees of empty ocean unaccounted for. This means that the distance from Portugal to China going west was 12,331 miles (half of the circumference). This would have been the combined equatorial spans of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans added together. These were the figures supplied by King Afonso’s advisors. No ship of that time was capable of a voyage of that distance without making landfall to replenish essential supplies.

However, Columbus started his calculations with a mistake of the first magnitude. Over the centuries, the circumference of the earth and Ptolemy’s map had been translated from Greek stadia into Arabic miles. Columbus assumed that they were using Roman miles, which are 20% shorter that the Arabic miles. This meant that Columbus’ world was 20% smaller than it really is. His second error was using Marinus of Tyre’s estimate that the longitudinal span of Eurasia was 225 degrees, which would have the effect of reducing the Pacific/Atlanic Ocean by 2,520 miles, and he followed this error up by taking Marco Polo’s estimate that Japan lay 1,500 miles from the coast of China reducing the distance from Portugal to Japan to 9,500 miles. If he sailed from the Canaries, he would reduce that distance by a further 500 miles. Columbus was also influenced by Toscanelli’s claim that there were inhabited islands even farther to the east than Japan, including the mythical Antillia.

Toscanelli's map of the Atlantic Ocean.

The final figure of 9,000 miles is daunting enough, but Columbus had presented his estimate of the distance from the Canaries to Japan as 5,300 miles when he was asking for funding. This is why nobody took him seriously. We know now that the real distance from Africa to Japan is more like 14,000 miles, and it is clear that Columbus and his crews would have disappeared without trace.

The only thing that saved them was something that nobody in the world suspected; just over 3,500 miles west of the Canaries was a huge hourglass shaped continent that stretched almost from pole to pole.

Leif Ericson stepping ashore in America painted by Hans Dahl.

Actually, there were some people who knew that there was a landmass not too far out in the Atlantic. Five-hundred years earlier, the Vikings had extensively sailed in the North Atlantic. The only two known mentions of the new lands are found in the work of Adam of Bremen c. 1075 and in the Book of Icelanders compiled c. 1122 by Ari the Wise. Leif Ericson was a Norse explorer from Iceland, and according to the sagas of Icelanders, he established a Norse settlement at a place called Vinland, which is usually interpreted as being coastal North America. There is still speculation that the settlement made by Leif and his crew corresponds to the remains of a Norse settlement found in Newfoundland, Canada, called L'Anse aux Meadows and which was occupied around the year 1000. The Saga of Erik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders, both thought to have been written around 1200, contain different accounts of the voyages to Vinland.

One story that is neither proven nor denied is that whilst Columbus was returning for his visit to Iceland in 1477 his ship stopped at Galway, and while they were there, he saw a man and a woman who had been found in an open boat in the Atlantic and picked up. Columbus wrote in his notes that they were of a “most unusual appearance.” Columbus must have added this to already stretched-to-the-limit theory about a westerly passage to the orient.

Columbus had travelled to Iceland, where the sagas and history of Lief Ericson were known. Had he learned of his travels and discoveries, he might have tried a more northerly route where there were plenty of stopping off places and sheltered harbours along the way. It might have helped him with his next big problem; finding a crew and captains who were willing to go with him on a suicidal voyage.

2

Like

Published at 10:15 AM Comments (0)

2

Like

Published at 10:15 AM Comments (0)

A new beginning, but the same old greed.

Friday, October 15, 2021

The beginning of Spain as a country and not an affiliation of kingdoms occurred on on19 October 1469 when Isabel married Ferdinand at the Palacio de los Vivero in Valladolid. The wedding united Castile, León and Aragon to form the basis for one state, which became the nascent country called after its ancient name of Hispania, later changed to España. The united kingdoms still continued to govern themselves as separate entities, but the seeds had been sown for something greater. However, the stability of Hispania was far from secure.

In May 1475, King Alfonso of Portugal and his army crossed into Spain and advanced to Plasencia. Here he married Juana, the only other contender for the Crown of Castile besides Isabel, and started a war to claim the Castilian crown. The war raged back and forth for almost a year until 1 March 1476, when the Battle of Toro took place, a battle in which both sides claimed victory, but neither won.

The armies fought each other to a standstill, but the outcome was indecisive and King Alfonso was forced to retreat and regroup his forces. Ferdinand showed his genius by sending messengers out to all the cities of Castile and the kingdoms nearby, that he had crushed the Portuguese in a great military victory. Overnight, support for Juana collapsed.

To avoid further bloodshed and a war they could not afford, Isabel and Fernando granted King Alfonso of Portugal the exclusive right of navigation and commerce in all of the Atlantic Ocean south of the Canary Islands, which meant that Hispania was practically blocked out of the Atlantic and deprived of the gold of Guinea. Since the time of the Phoenicians, roughly a third of the gold coinage in use around the Mediterranean had been minted from the gold produced by these mines.

The treaty of Alcáçovas, as it came to be known, created unrest among Andalucia’s nobles, who feared that they had bought peace at too high a price and had restricted their expansion into the Atlantic. The Kingdom of Portugal authorized a series of voyages down the coast of Africa encouraged by Pope Alexander VI in a 4 May 1493 papal decree, Inter caetera, which supported the treaty on the proviso that both Spain and Portugal promised to convert any indigenous people that they found to Christianity. This contract turned out to be just between Spain, Portugal and the pope, because the rest of Europe ignored it completely. However, the deeply pious Isabel saw the expansion of Spain’s sovereignty inextricably paired with the evangelization of non-Christian peoples.

Law and order had broken down within Castile and Aragon, and Isabel and Ferdinand created a militia whose sole purpose was to police their kingdoms and eliminate the robber bands that plagued traders. She gradually gained more control of the economy, and stability returned, but a cancer was growing in the form of hatred and intolerance for those who were not Christians. Posters began to appear depicting Jews as necromancers with dark and evil rituals. In 1478, while Ferdinand and Isabella were still consolidating their kingdom, they made formal application to the Pope for a tribunal of the Inquisition in Castile, to investigate these and other suspicions.

Isabel and Fernando had run up huge debts fighting for the crown. The Church did not lend money, it just collected it, and the only people who had been untouched by the costly Christian wars were the non-Christians who lived within their lands. They were not obliged to fund armies or fight, but they had profited well from the costly wars. They were predominantly Jews and Moors, who had served as doctors, builders, metalworkers, joiners and accountants. Here was a source of badly needed money for the crown. Most tempting of all for a bankrupt country, and the cause of much jealousy and hatred, was the Islamic Caliphate of Granada with its rich farmlands. Isabel set herself on a quest to rid Hispania of the Moors forever.

She embarked upon a ten-year-long war of sieges, defending Christian held castles and towns, and mounting skirmishes and ambushes in mountain defiles. It was a war that required the skills of a military engineer and a guerrilla fighter in equal measure. Every spring she mounted a new offensive against the Caliphate and gained more ground. Fernández de Gonzalo Córdoba became one of Isabel’s leading generals during the final years of the reconquest. Gonzalo had fought for Isabella against Portugal under Alonso de Cárdenas, the grand master of the Order of Santiago, and in the final battle that secured Isabel’s crown in 1479 he gained the praise of Cárdenas. Gonzalo Córdoba had other talents that placed him at the forefront of the Reconquista. He spoke the language of the Berbers fluently and was a one-time friend of Boabdil, the Caliph of Granada. At the end of the campaign, it was he who was chosen to lead the surrender negotiations. Gonzalo Córdoba would go on to be an innovative leader of the newly reformed Spanish army.

Gonzalo Córdoba Gonzalo Córdoba

Caliph Boabdil was overshadowed by his mother, Ayxa, who was a tyrant. She constantly intervened during the surrender negotiations, but she won him the right not to have to hand over the keys to the city to the Christians. The Moors were allowed to leave on their own accord and their caravan wound up to the mountain pass where they begin to descend towards the Mediterranean Sea. According to legend, it was here that Boabdil stopped to have one last look at his lost lands. Today it is marked by a small sign which says, Puerto del Suspiro del Moro. “The Pass of the Moor’s Sigh.” According to Washington Irving, the American writer, this is where Boabdil wept, and his callous mother berated him with the words “You do well to weep like a woman over what you could not defend as a man.” Irving did not invent the story; all the names and legends were there when he rode through in the 1820’s. The road up to the pass from Granada was called La Cuesta de Las Lagrimas, The slope of Tears.

Painting of Boabdil leaving Granada by Alfred Dehodencq

Isabel and Ferdinand watched the Moors leave before entering the city and raising their flag. During the surrender negotiations the year before, Isabel and Ferdinand had agreed to guarantee the Moors religious freedom under the Treaty of Granada. Nevertheless, Ferdinand burned over ten thousand Arabic manuscripts in a religious purge of the city.

During the previous year, when the king and queen were negotiating the surrender, a man who had been courting favour with them for the last five years had been invited to share in their triumph. Christopher Columbus had petitioned King John II of Portugal seven years earlier to fund a voyage to the west across the Atlantic to reach China. His terms were a little unreasonable; if successful, he would be awarded the title of “Admiral of the Ocean,” appointed governor of all the lands he discovered, and paid ten per-cent of their revenue. The King refused. He had made the same plea to King Henry VII of England and received the same answer. He tried Genoa and Venice to no avail, and now he was making the same offer to Isabel and Ferdinand. Advisors to the King and Queen decided that his ideas were too far-fetched and his guess at the distances involved fell woefully short. However, to stop him taking his ideas elsewhere, they gave him an allowance of 1200 Maravedís, and a letter granting him free lodgings and food wherever he went.

Christopher Columbus Christopher Columbus

In the spring before Granada fell, he was summoned to a final meeting with the King and Queen in Santa Fe, where Isabel and Ferdinand had their camp, and after a terse exchange, they refused the money he wanted. Columbus went away dejected, but he had made friends in court, and one of them was Luis de Santángel, a converso who was royal treasurer. Santángel convinced Isabel that other navigators and nations, especially the Portuguese, were discovering new lands which, for a small investment, could bring huge rewards. Isabel would have to fund the initial start-up and hope that other financers would share some of the costs. Castile and Isabel were so poor after the costly war against the Grenadans that she offered all her jewellery as collateral. In the legal double-talk of the time the promise of Isabella to pay was, in fact, a promise that she would later create an obligation for her subjects to pay; her jewels were never at risk.

Columbus had not gone four miles before he was called back to see the queen. He was to receive 10% of all portable valuables that he acquired from the voyage and would be granted the title of admiral. The real funding for the enterprise eventually came from a syndicate of seven noble Genovese bankers resident in Seville, with added funds supplied by Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de Medici. (Lorenzo was a fellow-student of Amerigo Vespucci who would become a friend and later an employee. Vespucci would send most of his famous letters on the New World to Lorenzo.) Because all the backers lived in Seville, all the accounting and recording of the voyage was kept in Seville, and the gold that eventually flowed back to Spain from the Americas was stored in the Torre del Oro in the docks.

Isabel was flushed with pride at her victory over the Moors, and the Church applauded her, but her finances were stretched after ten years of war. Columbus was a fool and would probably get himself and all his crew killed on his insane voyage. She did not give him a second thought, and instead looked to the assets that she had in Spain. She was already in negotiations with the king of England to marry her youngest daughter, Catherine, to the next-in-line for the English throne, Arthur. The trade deals were by far the largest part of the arranged marriage that poor 3-year-old Catherine was now bound into. However, there was a source of much needed revenue that was on her doorstep and easy to collect.

The anti-Semitic fervour had reached a peak now, and the Jews in Hispania were the lowest social group. The Mudéjar were treated better and had more rights than the Jewish population, but the Jews had more money; and money was what Isabel needed most. Just ten weeks after the fall of Granada, Isabel issued the Alhambra decree. It seems to have been all Isabel’s idea, and the theory is that her confessor had changed from the tolerant Hernado de Talavara, to the fanatical Francisco Jiménez de Cisternos.

The whole of the Christian world was balanced upon a pivot called Queen Isabel, and her decisions now were to point Hispania on the road to becoming a world superpower.

3

Like

Published at 12:33 PM Comments (0)

3

Like

Published at 12:33 PM Comments (0)

The rebels with a just cause

Friday, October 1, 2021

After the Dos de Mayo uprising whatever was left of the Spanish army scattered and hid in towns that were loyal to the crown. Slowly, and in secrecy, they contacted their comrades and sought refuge in the north of Spain, where the French presence was sparse. As with the Islamic invasion, the Picos de Europa provided a sanctuary for the dispossessed. Portugal was occupied by the French, but their friends, the British, had not forgotten them. The Portuguese royal family in exile in Brazil designated British generals to lead their loyal troops against Bonaparte’s troops, and a British force landed in Portugal under the command of 39 years-old General Arthur Wellesley.

In the first battle of what was to become known as the Peninsular War, Wellesley defeated a French division at the battle of Rolica on 17 August 1808. Four days later, he defeated a larger French force led by Major general Jean Andoche Junot at a town called Vimeiro near Lisbon. The French lost 2,000 men and 13 cannon, and the battle marked the beginning of the end for the French occupation of Portugal.

As with all his campaigns, Napoleon had planned meticulously for any event that could spoil them. Knowing that he was going to take over Spain after he had been invited in by Godoy, he forced the Spanish king to donate troops to fight in Europe with the Imperial French army. His idea was to dilute the Spanish army so that they would not be a problem when he seized control in Spain.

In March 1807, the Spanish Division of the North, comprised of 14 battalions of foot-soldiers and five regiments of cavalry, marched through France to assist in the Franco-Danish invasion of Sweden. They were commanded by Pedro Caro, 3rd Marquis of la Romana and were incorporated in a multinational force of Danish Germans and Italians led by Marshal Guillaume Brune. La Romana and his troops took part in the Siege of Stralsund in August 1807, but in the spring of 1808 they were led into Denmark to be part of a 30,000 strong army defending the coast.

This is exactly where Bonaparte wanted them when he installed his brother on the Spanish throne. The Spanish troops were watched very carefully by their French and Danish overlords, but when news of the Dos de Mayo uprising reached them, La Romana let it be known that he was going to fight the French. The Spanish troops had been deliberately spread out so that they could not easily assemble as a fighting unit.

But la Romana had already been approached in secret by the British, who offered to transport him and all the Spanish troops under his command back to Spain. With British help, La Romana embarked 9,000 of his troops onto captured Danish ships and sailed into the North Sea, where they were met by the Royal Navy. A few weeks later, they landed at Santander and were incorporated in the war against the French. Only one cavalry regiment and two infantry regiments failed to escape. The Spanish army was re-grouping, and they were happy to ally themselves with the Portuguese and British to force the French off their soil.

The Spanish armed forces were still no match for Napoleon’s Grand Armée, but the hope given by the re-capture of Portugal by British and Portuguese was enough to spur on Spanish civilians to fight the French. There is no better example of the ferocity of the Spanish spirit than the story of Juan Martin Díez, who was known by his nickname, or mote, as El Empecinado (From the verb to be persistent, empecinarse). He was born the son a farmer in Castrillo de Duero, Valladolid in1775, and the family house is still there today.

Díez was a rebel as a teenager, and his appetite for warfare led him to fight in the Rosellón campaign of the War of the Pyrenees, where he was baptised in the art of war. He must have calmed down after seeing the brutality of war, because in 1796 he married a girl in the town of Fuentecén, Burgos, and he and his young wife farmed the land peacefully for 12 years. But then French troops began to occupy the city and, according to the legend, one of the French troops raped one of the local girls. The rebel in Díez resurfaced, and he slipped out one night, found the rapist alone, and killed him. After the Dos de Mayo uprising Díez could not continue his life as a farmer, and the rebel had found his cause.

Díez organised local men into a makeshift army, even recruiting members of his own family. He lived on the main supply route for French troops defending the Portuguese border, and he began a series of attacks on the frequent wagon trains that passed through Burgos. As his reputation spread, more resistance fighters joined his ragged army, and the disruption to French supplies became a major problem for the French. They could not hope to win a stand-up fight with trained soldiers, but Díez’s hit-and-run tactics meant that French troops who could be defending against the ever-stronger British forces had to be diverted to protect their convoys. With the Spanish army’s ranks bolstered by new recruits, it began to make bolder stands against the French, but in the early stages of the war for independence, they were no match for the elite and battle hardened French troops led by experienced and clever generals.

Díez and his followers took part in some of these conventional battles, but each time they fought, the Spanish were routed. After the Spanish lost two battles in the area of Valladolid, the Cabezón de Pisuerga bridge and the Medina de Rioseco, Díez became convinced that fighting the French on their own terms was a serious mistake.

Díez began to train his army of guerrillas into small well-armed groups which could quickly move overland and strike anywhere. He was met with immediate success. After a number of lightning surgical strikes, notably Aranda de Duero, Sepúlveda and Pedraza, he and his groups disappeared into the countryside carrying away vital arms, ammunition and the gold coin needed to pay the French troops. They disrupted the French lines of communication which robbed the French of vital intelligence. Díez and his irregular army became the scourge of the Duero valley.

Juan Martin Díez Juan Martin Díez

He was promoted to the rank of cavalry captain in the Spanish army in1809, and he expanded his attacks to cities along the edge of the Sierras de Ávila. The French occupied areas of Gredos, Ávila, Salamanca, and the provinces of Cuenca and Guadalajara came under constant harassment from Díez’s marauders. His raids often gave the Spanish army more information on French strengths and dispositions than the French commanders had. For the French, he became the most hated and feared leader in the Spanish army, but to the Spanish people, he was a hero. This was the real threat that Díez posed to Napoleon, who was trying to hold down several occupied countries. When they saw how Spain was resisting and defeating French forces they were quick to copy Spanish tactics.

Bonaparte ordered one of his generals, Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo, to “pursue exclusively” Díez and his guerrillas. After several failed attempts to capture the guerrilla leader, Hugo arrested Díez's mother and other members of his family. Díez ordered the public execution of 100 French prisoners of war and promised more unless his family were released. Hugo, fearing loss of morale in his own forces by this action, backed down and released his family. Meanwhile, whilst Díez and the other Spanish resistance groups across Spain were creating havoc, General Wellesley was taking on the French in conventional battles and gaining ground. By 1813, Spanish guerrillas were tying down over 75% of the French occupying army, making Wellesley’s task that much easier.

The highest point of Díez’s career came at the defence of Alcalá de Henares, the old seat of the Catholic kings of Castille near to Madrid. On May 22, 1813 on the Zulema Bridge over the Rio Henares, Díez and his army defeated a French force twice their size. Of course, the rest of the story goes to the British forces led by Wellesley, who drove back and pursued Bonaparte’s army out of Spain and into France, finally defeating him at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

When Fernando VII returned to power as king of Spain in 1813 he approved the construction of a commemorative pyramid to Díez in Alcalá, but Fernando turned out to be a weak and fickle king. He hated the liberal constitution that the 1812 Cadiz Cortes Generales (General Courts, or Pepa) represented and repealed all its laws and ideals, reinstating himself as absolute monarch. From 1814 until his death in 1833, he suppressed the liberal press by throwing the writers and editors into prison. However, a popular liberal led revolt in 1820 forced Fernando to re-adopt the Pepa’s constitution. With the defeat of Napoleon, many of the kingdoms in Europe were seeing their royal families fighting to re-establish themselves, and the liberal ideals that the Spanish had approved in Cádiz represented a threat to them.

Fernando lobbied the other monarchs of Europe to support him, and he joined the Holy Alliance formed by Russia, Prussia, Austria and France. In France, the ultra-royalists pressured Louis XVIII to intervene in Spain to restore absolutism, and Ferdinand was complicit in the ultimate betrayal of the Spanish people by allowing the French to invade Spain once more. The liberal governing of Spain had lasted just three years, but in 1823 a French army once more crossed the Pyrenees.

By now Díez had returned to a quiet life, but upon hearing that the French were returning, he fled to Portugal. The king promptly ordered the destruction of the pyramid in Díez’s honour for the victory at Alcalá, deriding it as a symbol of a “liberal”. Díez asked the king for permission to return his homeland without the threat of imprisonment, and the king agreed.

As soon as he returned he was arrested and transported to Nava de Roa, Burgos, where the mayor displayed him in an iron cage. Leopoldo O'Donnell, one of the remaining liberal leaders heard of his imprisonment and pleaded to have his case heard in a tribunal, which would probably have granted his release, but the magistrate had already ordered his execution. Díez was hanged as a criminal on August 20, 1825 in the central plaza of the village, and the legend goes that he managed to snatch the sword of the official who accompanied him to the gallows in a last defiant gesture.

The people of Alcalá raised another monument to El Empecinado in 1879 and this monument survives to this day.

The monument to Díez in Alcalá

As you have probably guessed by now I am and avid reader of history. Up until recently I wrote reviews for the Historical Novel Society, and one of the books that I reviewed was a translation of Trafalgar and the Battle of Salamanca written by Benito Perez Galdós. These two stories are a part of the Episodios Nacionales, a series comprising 46 historical novels depicting the War of Independence. Galdós was born in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, in 1843, and he died in Madrid in 1920 aged 76. His father fought in the War of Indepenence and Benito first learned about the war from his father. His attention to detail and accuracy in his novels is illustrated by his research for the battle of Trafalgar, the first of his Episodios Nacionales novels published in 1873. He went to stay at Santander to write the novel, but he had only a history book for reference. One of his friends told him that there was an 83 year-old survivor of the battle living nearby, and Galdós went to talk to the old man every day. He had served on the Spanish flagship, Santisima Trinidad, as a cabin boy, and the wealth of information that the old man gave him enabled him to re-create him as Gabriel Araceli, the main character in several of his novels.

Cover painting by Joaquín Sorolla. Cover painting by Joaquín Sorolla.

0

Like

Published at 9:55 AM Comments (2)

0

Like

Published at 9:55 AM Comments (2)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|