The beginning of Spain as a country and not an affiliation of kingdoms occurred on on19 October 1469 when Isabel married Ferdinand at the Palacio de los Vivero in Valladolid. The wedding united Castile, León and Aragon to form the basis for one state, which became the nascent country called after its ancient name of Hispania, later changed to España. The united kingdoms still continued to govern themselves as separate entities, but the seeds had been sown for something greater. However, the stability of Hispania was far from secure.

In May 1475, King Alfonso of Portugal and his army crossed into Spain and advanced to Plasencia. Here he married Juana, the only other contender for the Crown of Castile besides Isabel, and started a war to claim the Castilian crown. The war raged back and forth for almost a year until 1 March 1476, when the Battle of Toro took place, a battle in which both sides claimed victory, but neither won.

The armies fought each other to a standstill, but the outcome was indecisive and King Alfonso was forced to retreat and regroup his forces. Ferdinand showed his genius by sending messengers out to all the cities of Castile and the kingdoms nearby, that he had crushed the Portuguese in a great military victory. Overnight, support for Juana collapsed.

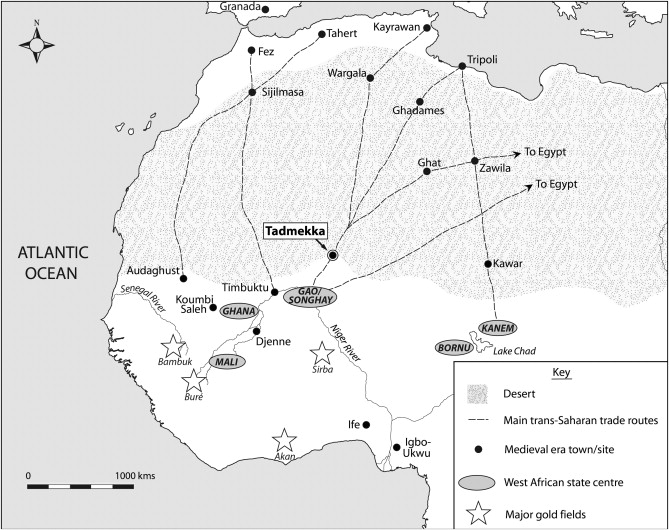

To avoid further bloodshed and a war they could not afford, Isabel and Fernando granted King Alfonso of Portugal the exclusive right of navigation and commerce in all of the Atlantic Ocean south of the Canary Islands, which meant that Hispania was practically blocked out of the Atlantic and deprived of the gold of Guinea. Since the time of the Phoenicians, roughly a third of the gold coinage in use around the Mediterranean had been minted from the gold produced by these mines.

The treaty of Alcáçovas, as it came to be known, created unrest among Andalucia’s nobles, who feared that they had bought peace at too high a price and had restricted their expansion into the Atlantic. The Kingdom of Portugal authorized a series of voyages down the coast of Africa encouraged by Pope Alexander VI in a 4 May 1493 papal decree, Inter caetera, which supported the treaty on the proviso that both Spain and Portugal promised to convert any indigenous people that they found to Christianity. This contract turned out to be just between Spain, Portugal and the pope, because the rest of Europe ignored it completely. However, the deeply pious Isabel saw the expansion of Spain’s sovereignty inextricably paired with the evangelization of non-Christian peoples.

Law and order had broken down within Castile and Aragon, and Isabel and Ferdinand created a militia whose sole purpose was to police their kingdoms and eliminate the robber bands that plagued traders. She gradually gained more control of the economy, and stability returned, but a cancer was growing in the form of hatred and intolerance for those who were not Christians. Posters began to appear depicting Jews as necromancers with dark and evil rituals. In 1478, while Ferdinand and Isabella were still consolidating their kingdom, they made formal application to the Pope for a tribunal of the Inquisition in Castile, to investigate these and other suspicions.

Isabel and Fernando had run up huge debts fighting for the crown. The Church did not lend money, it just collected it, and the only people who had been untouched by the costly Christian wars were the non-Christians who lived within their lands. They were not obliged to fund armies or fight, but they had profited well from the costly wars. They were predominantly Jews and Moors, who had served as doctors, builders, metalworkers, joiners and accountants. Here was a source of badly needed money for the crown. Most tempting of all for a bankrupt country, and the cause of much jealousy and hatred, was the Islamic Caliphate of Granada with its rich farmlands. Isabel set herself on a quest to rid Hispania of the Moors forever.

She embarked upon a ten-year-long war of sieges, defending Christian held castles and towns, and mounting skirmishes and ambushes in mountain defiles. It was a war that required the skills of a military engineer and a guerrilla fighter in equal measure. Every spring she mounted a new offensive against the Caliphate and gained more ground. Fernández de Gonzalo Córdoba became one of Isabel’s leading generals during the final years of the reconquest. Gonzalo had fought for Isabella against Portugal under Alonso de Cárdenas, the grand master of the Order of Santiago, and in the final battle that secured Isabel’s crown in 1479 he gained the praise of Cárdenas. Gonzalo Córdoba had other talents that placed him at the forefront of the Reconquista. He spoke the language of the Berbers fluently and was a one-time friend of Boabdil, the Caliph of Granada. At the end of the campaign, it was he who was chosen to lead the surrender negotiations. Gonzalo Córdoba would go on to be an innovative leader of the newly reformed Spanish army.

Gonzalo Córdoba

Gonzalo Córdoba

Caliph Boabdil was overshadowed by his mother, Ayxa, who was a tyrant. She constantly intervened during the surrender negotiations, but she won him the right not to have to hand over the keys to the city to the Christians. The Moors were allowed to leave on their own accord and their caravan wound up to the mountain pass where they begin to descend towards the Mediterranean Sea. According to legend, it was here that Boabdil stopped to have one last look at his lost lands. Today it is marked by a small sign which says, Puerto del Suspiro del Moro. “The Pass of the Moor’s Sigh.” According to Washington Irving, the American writer, this is where Boabdil wept, and his callous mother berated him with the words “You do well to weep like a woman over what you could not defend as a man.” Irving did not invent the story; all the names and legends were there when he rode through in the 1820’s. The road up to the pass from Granada was called La Cuesta de Las Lagrimas, The slope of Tears.

Painting of Boabdil leaving Granada by Alfred Dehodencq

Isabel and Ferdinand watched the Moors leave before entering the city and raising their flag. During the surrender negotiations the year before, Isabel and Ferdinand had agreed to guarantee the Moors religious freedom under the Treaty of Granada. Nevertheless, Ferdinand burned over ten thousand Arabic manuscripts in a religious purge of the city.

During the previous year, when the king and queen were negotiating the surrender, a man who had been courting favour with them for the last five years had been invited to share in their triumph. Christopher Columbus had petitioned King John II of Portugal seven years earlier to fund a voyage to the west across the Atlantic to reach China. His terms were a little unreasonable; if successful, he would be awarded the title of “Admiral of the Ocean,” appointed governor of all the lands he discovered, and paid ten per-cent of their revenue. The King refused. He had made the same plea to King Henry VII of England and received the same answer. He tried Genoa and Venice to no avail, and now he was making the same offer to Isabel and Ferdinand. Advisors to the King and Queen decided that his ideas were too far-fetched and his guess at the distances involved fell woefully short. However, to stop him taking his ideas elsewhere, they gave him an allowance of 1200 Maravedís, and a letter granting him free lodgings and food wherever he went.

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

In the spring before Granada fell, he was summoned to a final meeting with the King and Queen in Santa Fe, where Isabel and Ferdinand had their camp, and after a terse exchange, they refused the money he wanted. Columbus went away dejected, but he had made friends in court, and one of them was Luis de Santángel, a converso who was royal treasurer. Santángel convinced Isabel that other navigators and nations, especially the Portuguese, were discovering new lands which, for a small investment, could bring huge rewards. Isabel would have to fund the initial start-up and hope that other financers would share some of the costs. Castile and Isabel were so poor after the costly war against the Grenadans that she offered all her jewellery as collateral. In the legal double-talk of the time the promise of Isabella to pay was, in fact, a promise that she would later create an obligation for her subjects to pay; her jewels were never at risk.

Columbus had not gone four miles before he was called back to see the queen. He was to receive 10% of all portable valuables that he acquired from the voyage and would be granted the title of admiral. The real funding for the enterprise eventually came from a syndicate of seven noble Genovese bankers resident in Seville, with added funds supplied by Lorenzo di Pier Francesco de Medici. (Lorenzo was a fellow-student of Amerigo Vespucci who would become a friend and later an employee. Vespucci would send most of his famous letters on the New World to Lorenzo.) Because all the backers lived in Seville, all the accounting and recording of the voyage was kept in Seville, and the gold that eventually flowed back to Spain from the Americas was stored in the Torre del Oro in the docks.

Isabel was flushed with pride at her victory over the Moors, and the Church applauded her, but her finances were stretched after ten years of war. Columbus was a fool and would probably get himself and all his crew killed on his insane voyage. She did not give him a second thought, and instead looked to the assets that she had in Spain. She was already in negotiations with the king of England to marry her youngest daughter, Catherine, to the next-in-line for the English throne, Arthur. The trade deals were by far the largest part of the arranged marriage that poor 3-year-old Catherine was now bound into. However, there was a source of much needed revenue that was on her doorstep and easy to collect.

The anti-Semitic fervour had reached a peak now, and the Jews in Hispania were the lowest social group. The Mudéjar were treated better and had more rights than the Jewish population, but the Jews had more money; and money was what Isabel needed most. Just ten weeks after the fall of Granada, Isabel issued the Alhambra decree. It seems to have been all Isabel’s idea, and the theory is that her confessor had changed from the tolerant Hernado de Talavara, to the fanatical Francisco Jiménez de Cisternos.

The whole of the Christian world was balanced upon a pivot called Queen Isabel, and her decisions now were to point Hispania on the road to becoming a world superpower.