Begging for mercy

Friday, February 25, 2022

Whilst Columbus had been away discovering the South American mainland, the unrest had grown in Hispaniola, and the lobbying against the Columbus brothers in the court of Queen Isabel and King Ferdinand caused them to reconsider his status and the promises that they had made him when he was asking for funding. In October 1499, Columbus had sent a letter to the queen asking her to send him somebody to help him govern. Clearly, from the reports coming from the colony, something was going wrong. Isabel asked one of her closest advisors and friends, Francisco de Bobadilla, if he would go to Hispaniola to discover what was happening in her new colony. He arrived in Santo Domingo in August 1500 whilst two of the Columbus brothers were away.

Bobadilla was a member of the Order of Calatrava, a position high in the hierarchy of the nobility of España. Columbus and his brothers were not even Spanish, and were rank outsiders as far as nobility was concerned. Columbus may have been an excellent explorer, but the game had changed, and the big players were moving in. Bobadilla immediately began to investigate the accusations of brutality and corruption. Seven Spaniards had already been hung, with another five awaiting execution. Bobadilla’s instructions from the queen were to ascertain:

“Which persons were the ones who rose up against the admiral and our justice and for what cause and reason, and what damage they have done. Detain those whom you find guilty and confiscate their goods.”

He used force to stop the executions and confiscated Columbus’ possessions, including all the papers that he would need to prove his innocence. He suspended the much-abused tribute system and in October 1500 summoned the Admiral to face the charges made against him. Columbus was ordered to relinquish all control of the colonies, but was allowed to keep his personal wealth. Columbus’ son, Ferdinand, recorded that Bobadilla:

“Took testimony from their open enemies, the rebels, and even showing open favor,” and auctioned off some of his father's possessions “for one third of their value.”

The charges against Columbus were many and grievous. He was accused of preventing the priests from baptising the natives, (One of Isabel’s conditions for his funding was the conversion of the natives to Christianity.) Allegedly, he captured a tribe of 300 natives to be sold into slavery and told all the Christians who employed natives to give him half of them to sell as slaves. There were lists of accusations of brutality to Spanish settlers and overly severe punishments for minor crimes. The worst of the charges was that he had allowed 50 men to starve to death in La Isabela when he had imposed severe rationing of food whilst in actual fact there was an abundance of supplies. Columbus was put in chains at his own request, and he and his brothers were sent back to España to stand trial in the royal court.

In the eight years since Columbus’ first voyage, Isabel had changed the way España was run. After overturning the 700 year rule of the Moors and forcing them out of the country, she had given the Jews an ultimatum; convert to Christianity or leave. The alternative was torture and death. She established a rudimentary police force throughout her kingdoms which was more paramilitary than law enforcement. This was to curb the lawlessness that had replaced the structured society of the Moors as they were driven out of España. During the reconquest, the makings of a dedicated military service governed by the Church had begun to form. The Templars, Knights Hospitaller and the Order of Calatrava were distinct and powerful entities with their own hierarchy of command. Isabel and Ferdinand ruled their kingdoms, but the Catholic Church ruled them, and every other Christian country in Europe. Isabel’s confessor was Archbishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, and it was he who was given the job of replacing Columbus’ haphazard rule with something more controllable, or rather, controlled more by the church. Fonseca was instrumental in forming España’s colonial policy. It was he who established the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) in1503. As well as keeping track of which ships were trading with the Indies, and what their cargoes were, the Casa de Contratación controlled immigration. Prospective settlers were vetted to make sure that they were of old Christian heritage and had no Jewish or Muslim tornadizos in their family history. Finally, the church had control of the financial and judicial control of trade with the Indies.

As Columbus was being ferried across the Atlantic in chains, another explorer was setting off in the opposite direction at the head of a fleet of 13 ships. In 1488 when Columbus had been touting his insane idea all over Europe, he had been rebuffed by King John II of Portugal. Isabel had a bankrupt and fractured country after centuries of reconquest, but King John was less controlled by the church and only had a balance of payments problem. Since he came to power in 1481, John had been looking for ways to increase trade with the orient. He was eager to break into the highly profitable spice trade between Europe and Asia, which was conducted chiefly by land. At the time, this was virtually monopolized by the Republic of Venice, who operated overland routes via Levantine and Egyptian ports, through the Red Sea across to the spice markets of India. He set a new objective for his captains: to find a sea route to Asia by sailing around the African continent.

In October, 1486, King John commissioned Bartolomeu Dias to lead an expedition in search of a trade route around the southern tip of Africa. Dias was provided with two caravels of about 50 tons each and a square-rigged supply ship captained by his brother Diogo. He recruited some of the leading pilots of the day, including Pêro de Alenquer and João de Santiago. Sometime in February 1487 they rounded the tip of Africa and noted that they were sailing north in a new ocean. The crew and officers made it clear that they had achieved their objective and should now return home. On the return trip, they once again passed the southernmost point of Africa. Dias named it the Cape of Storms (Cabo das Tormentas), but the story is that King John II later renamed it the Cape of Good Hope (Cabo da Boa Esperança) because it symbolized the opening of a sea route from west to east. This was a significant event that went pretty much unrewarded. King John was preoccupied; he had lost a son in a war in Morocco, and his health was failing. A decade went by before Portugal mounted any more expeditions.

This was not the first time that Dias had sailed down the coast of Africa. His family had a maritime background, and one of his ancestors, Dinis Dias e Fernandes, explored the African coast in the 1440s and discovered the Cape Verde islands in 1444.

Dias had been part of an expedition, led by Diogo de Azambuja, to construct a fortress and trading post called São Jorge da Mina in the Gulf of Guinea. There is also evidence that he may have joined Diogo Cão's first expedition down the African coast to the Congo River in 1482. Diogo Cão had made two voyages to try to reach the southern end of the continent of Africa, but had failed both times. Knowing all this, King John had turned away Columbus with his ridiculous idea that he could sail west to China. He didn’t need this idiot. He already had the trade route to China that he wanted.

By the time that Columbus had returned from his third voyage in 1499, Portugal had a new king. Manuel I was the grandson of King Edward, the father of king of John II. He and his advisors were determined to follow the same ambitious plans of exploration the John had started. It was obvious now that Columbus had stumbled on a new continent that had hitherto been unknown. When the pope moved the line of the old Treaty of Tordesillas to its new position in 1494, King John was happy knowing that he had the whole of Africa to trade with and the possibility of a trade route with the orient via the Cape of Good Hope. But the new discoveries to the west of the line were becoming very alarming. It seemed that España was entitled to claim a huge undiscovered continent whilst Portugal was shut out.

King John had never been one for waiting for events to overrun him. As early as 1487, he had dispatched two spies, Pero da Covilhã and Afonso de Paiva, overland via Egypt and East Africa and India, to scout the details of the spice markets and trade routes. If he could get to India by sea, he knew where to establish his trading centres.

Vasco da Gama leaving Portugal. Biblioteca National de Portugal.

Whilst Columbus was in the Caribbean on his second voyage, King John equipped a fleet under the command of Vasco da Gama. They sailed in 1497 and rounded the Cape of Good Hope without problems to finally land at Calicut in India in May 1498. Portugal now had unopposed access to the source of the spices that had made the Republic of Venice the richest city-state in the Mediterranean. When the seasonal winds and currents in the southern hemisphere were charted and understood, convoys of trading ships were to make regular annual trips to India and back. In 1524 da Gama was appointed Governor of India, with the title of Viceroy, and was ultimately ennobled as Count of Vidigueira in 1519.

Vasco da Gama

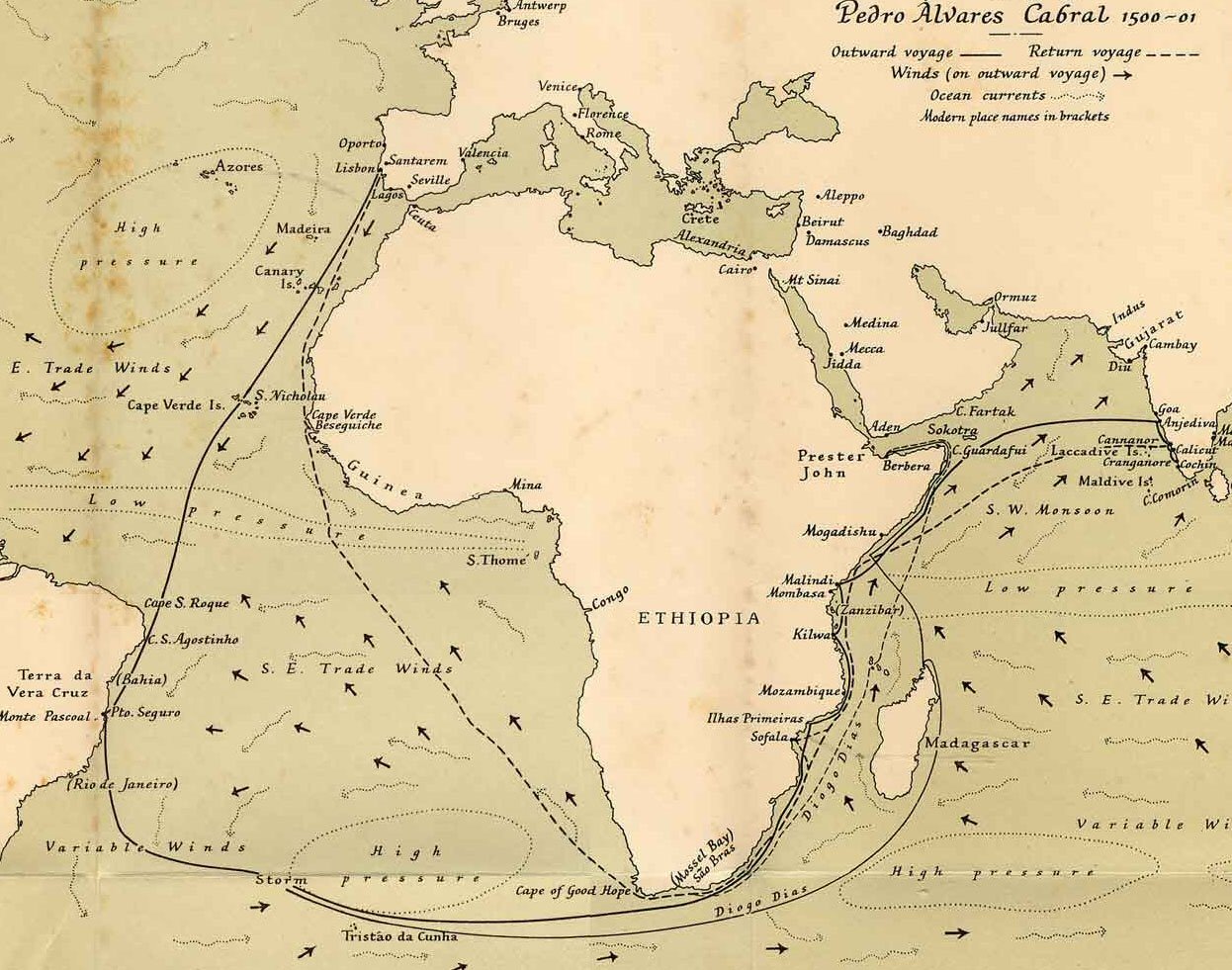

With this success under his belt, Manuel I turned his attention to the west again. Vasco da Gama had reported seeing signs of land to the west when his fleet sailed down the mid-Atlantic. He commissioned Pedro Álvares Cabral, a 32 year-old nobleman who was a military commander and navigator to lead an expedition and Bartolomeu Dias was asked advise on the type of ship that he would need for the new long-distance trade routes that were opening up. In 1500, the fleet of 13 ships sailed into the Atlantic, and whether on purpose or driven by storm, they landed on what turned out to be the coast of modern-day Brazil. Cabral was not that good a celestial navigator, and with the instruments of the day it was hard to tell where the Tordesillas line fell, which meant that nobody else could conclusively prove him wrong. As it turned out, he was well within the region that the pope had allowed Portugal to claim. Cabral did not hesitate; he promptly claimed this new continent for Portugal and sent one of his ships back to take the king the news. He re-provisioned his ships and continued with the rest of the fleet to round the Cape of Good Hope and sail to India.

Cabral and his ships became the first mariners to touch four continents in one voyage. They sailed from Europe to South America, then to Africa and India. His voyage was not without peril. Several ships were lost in a storm in the Sothern Atlantic, and when he reached Calicut in India, Arab traders had mounted an attack on Portuguese assets on the coast. Cabral attacked the Arab fleet and burned and looted their port in retaliation. The Portuguese trading empire would eventually stretch from the Americas to the Far East, and its navigators and captains would be envied and feared throughout the world.

1

Like

Published at 10:59 AM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 10:59 AM Comments (1)

From acclaim to accusation

Friday, February 11, 2022

After news of the first two voyages of Christopher Columbus had become widespread, every maritime nation throughout Europe scrambled for a slice of the action. They would chiefly be funded, sometimes with an unlimited budget, by King John II, and his successor Manuel I of Portugal, Henry VII of England and Isabel and Ferdinand of España. The widespread publication of his letters describing the islands that he had discovered galvanised maritime adventurers across Europe, and exploration was to become the game of the century.

When Columbus set sail on his second voyage in 1493, Juan de la Cosa accompanied him, but again, he is barely mentioned. (The log for the second voyage has never been found.) However, he appears in official records when he claims compensation for the loss of his ship, the Santa Maria. In a letter to de la Cosa, the king and queen give him praise and recompense for his ship.

“Salutations and thanks to you Juan de la Cosa … you have given us good service and we hope that you will help us from now on. In our service at our mandate you sailed as captain of a nao of yours … during which the lands and islands of the Indies were discovered, you lost your nao … In payment and satisfaction we hereby give you license and faculty to take from the city of Jerez de la Frontera, or from any other city or town or province of Andalusia, two hundred cahises of wheat to be loaded and carried from Andalusia to our province of Guipúzcoa, and to our county and the lordship of Vizcaya, and not elsewhere.”

This indicates that Juan de la Cosa was a trader as well as an explorer and cartographer. It also hints that he owned at least one other ship. In any case, the letter arrived too late; he had already set off with Columbus on his second voyage when it arrived, but even though he had been side-lined in the Columbus logs, he was fast becoming a significant player in the exploration of the New World.

When the third voyage sailed, it would be documented by Bartolomé de Las Casas, and its objective was to prove or disprove a claim made by King John II of Portugal, who had proposed that there was a much larger mainland to the south-west of the islands that Columbus had discovered. The king’s theory was based on reports that “canoes had been found which set out from the coast of West Africa (Cape Verde Islands) and sailed to the west with merchandise.” The travellers’ tales that had been dismissed as fables by previous mariners were now being examined more closely. Columbus left with six ships from Sanlúcar de Barrameda on 30 May 1498, but his search for a mainland had already been anticipated by another native of Genoa.

A replica of the Matthew in Bristol, England. Photo: Chris McKenna.

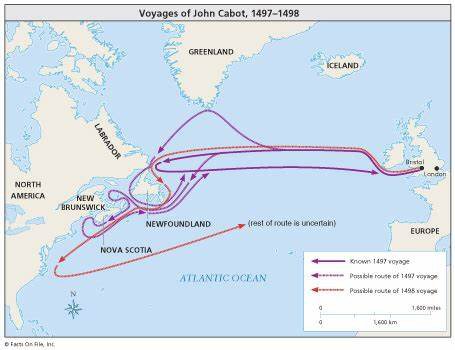

In May 1497 John Cabot had set off from Bristol with a crew of 18 in a boat named Matthew which was little larger than a fishing smack. Cabot had been born in Genoa, but had settled in England and had made several voyages out into the Atlantic searching for islands to use as staging posts to extend his exploration further west. When the news came of Columbus’ first voyage and discovery, he provisioned his ship and sailed due west from England. On June 24 he landed at what he thought was an island off north-east Asia, but was almost certainly Cape Bretton Island, at the entrance to the St. Lawrence Seaway, gateway to the great lakes of North America. On his return to England in August 1497 King Henry VII awarded him a pension of £20 and a prize of £10.

Whilst Cabot was away, a Portuguese navigator had sailed from Iceland to Greenland, which he supposed to be the extreme north-east of Asia. Cabot learned of this, and now infused with confidence after his success, decided to try this more northerly route. With the backing of the king, he set sail with two ships whose combined crews amounted to 300 sailors. They sailed in May 1498 (more or less the same time that Columbus sailed.)reaching Greenland in June and continued north until icebergs and a mutinous crew made Cabot turn south. He sailed offshore of Baffin Island, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia and New England on his way south. Cabot found no signs of an Asian civilisation, and watching his dwindling supplies, decided to return to England. He reported his finds to the king when he arrived in the autumn, but Cabot died shortly after his return. King Henry, however, realised the significance of the discovery, and later claimed the whole of North America as an English possession.

All of these mariners were sailing into the unknown. The birthplace of sailing, the Mediterranean Sea, can generate fierce storms, but they pale into insignificance in comparison to the North-Atlantic. Columbus had discovered dozens of islands in the Atlantic, but that was all they were; islands. Cabot had discovered a mainland, but he had no idea how big it was. For his third voyage, Columbus now had a mission to find out if there was a bigger landmass further south-west.

Three of Columbus’ six ships were taking much-needed supplies to La Isabela on Hispaniola, and they sailed directly there. The remainder of Columbus’ fleet sailed to Porto Santo first and then to Madeira, where he spent time comparing notes with the Portuguese captain João Gonçalves da Camara. Finally, they sailed to the Cape Verde islands via the Canaries and took on supplies before setting out across the Atlantic.

Despite seeking all the advice that he could gather on the southern Atlantic, his fleet ran straight into one of its perils. On the 13 July his ships became becalmed in the doldrums. They were not far from the equator, and the sun beat down on the hapless ships, making working on deck during the day impossible. More dangerous, the above water timbers dried out and shrank, loosening joints and leaving gaps in the planking. Barrels of provisions suffered the same fate, and the contents of ones that were open began to putrefy. The dehydration of the crew meant that the consumption of precious fresh water accelerated to critical levels. Mercifully, an easterly wind finally arrived to push them out of the inferno.

On July 31 they sighted the island of Trinidad and sailed to its most south-western point, where they met with natives in canoes who had come from the west. The fleet sailed west and on 1 August arrived at the delta of the Orinoco River. Columbus realised that the delta was sure proof of a huge river system further west; he had found the southern continent. They entered a tidal race now called the serpent’s mouth into the Gulf of Paria, a bay enclosed by Trinidad to the east and South America to the west, and on the following day they landed on the west coast of Trinidad where they met stiff resistance from the natives and were forced to return to their ships to escape the attack. This was not the end of his trials, because early in the morning of August 4, the fleet narrowly missed another disaster when a tsunami swept into the bay and almost capsized the flagship.

For seven years Columbus had been the acclaimed discoverer of the Indies. He had been at the centre of a social, political and maritime revolution. He had suffered betrayals and hostility from his crews and challenges to his authority. In all of his voyages of discovery he had led from the front, through storms at sea and political intrigues at home, he had carried the flag of España, and it was this flag that was planted at the northern end of the bay on the Paria Peninsula to claim South America for España.

But Columbus did not go ashore. During the previous month he had been suffering from insomnia. It may have been caused by the constant stress of command and the ever present danger. His eyes had become bloodshot and he had difficulty seeing. The other captains planted the flag, erected a cross and read the speeches. Sometime later he went ashore in his official capacity to claim the find, but his health was now uncertain. At least the natives here were friendlier and gave him food, and he topped up his barrels with fresh water.

They returned to Hispaniola to find that there was a full scale rebellion going on amongst the Spanish settlers who had been promised rich farmlands and gold. Some of them had taken passages on returning supply ships and were now lobbying the king and queen, claiming that they had been misled and that Columbus was guilty of gross mismanagement. He hung some of his crew for disobedience and faced criticism from the church, which was disappointed that none of the natives had been converted to Christianity. In fact, Columbus was making quite a lot of money shipping them back to Spain and selling them as slaves. Finally cornered, Columbus had to agree to humiliating terms and he was removed as governor. He was arrested and put in manacles for transportation back to España where he would face the charges against him. When they ordered his crew to fasten the iron bands around his wrists they refused. None of the other captains or their crews would shackle him, and it was left to his ship’s cook who very reluctantly put him in chains. Even then, it was only because of Columbus’ insistence that the cook did what nobody else was prepared to do.

The exploitation of the natives continued unabated, and so did the exploration of the oceans. The next three years saw an explosion of voyages as the seagoing countries of Europe mounted expedition after expedition and the map makers struggled to keep track of the discoveries. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel of España had the lion’s share of the discoveries, but England and Portugal were about to claim some of the new lands and the huge profits that they would bring.

1

Like

Published at 10:13 AM Comments (1)

1

Like

Published at 10:13 AM Comments (1)

Spam post or Abuse? Please let us know

|

|