Last week’s post told of the invasion of Iberia by Musa bin Nusayr, the governor of the Arab province of Ifriqiya. At first, the newly conquered lands were administrated from Ifriqiya as a province of the Umayyad Empire, its governors appointed by the emir of Kairouan rather than the emir in Damascus. The conquerors renamed Iberia al-Andalus, and settlers began to flood in to occupy the relatively fertile land and establish a regional capitol in Córdoba.

Those Visigoth Dukes who recognised the authority of their new masters were allowed to keep their lands, creating areas around Murcia, Galicia and the Ebro valley where little changed. Those who could not live with the Muslims formed a refuge in the inaccessible Cantabrian highlands, where they re-grouped and defended their Kingdom of Asturias.

Having consolidated their gains in al-Andalus, the governors of the province sent Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi to make raids into the lands beyond the eastern Pyrenees, but he was driven back by Duke Odo the Great of Aquitaine. Undeterred, he crossed the mountains further west and attacked again, this time defeating the duke. He pushed further east into the old Roman province of Septimania, capturing Arles and Avignon and probing north following the river Rhone before he was stopped by a stronger Bergundian force led by Charles Martel at the Battle of Poitiers in 732. A coalition of Lombardians and Bergundian armies drove Al Ghafiqi back to the Pyrenees before finally expelling them from Gaul by 739.

The Mulsim invasion forces had been drawn from African Berbers with some Arabs of Ifriqiya and the Levant, but relations between the different cultures was strained in the years following the invasion. The Berbers had borne the brunt of the fighting to capture Iberia and vastly outnumbered the Arabs from the Levant, who now flooded in and took key posts in the administration, forcing the Berbers into a secondary, subservient role. Some of the new Arab governors began to mistreat their Berber counterparts, and before long, the Arabs had a Berber revolt on their hands. The Berbers had railed against their Arab overlords before in 729 and had even managed to carve out their own rebel state in Cerdanya, but the big revolt started in the Maghreb in 740.

To put down the uprising, the Umayyad Caliph, Hisham, sent a large Syrian army to Morocco. At the Battle of Bagdoura, the Syrians were soundly defeated by the Berbers. The news of their brothers’ success travelled to northern Iberia, where the mistreated Berbers also mutinied and deposed their Arab commanders. They formed a rebel army and marched against the Arab administrative centres of Toledo, Cordoba, and al-Jazeera. (Algeciras)

In response, the caliph in Damascus rallied his armies and sent 10,000 troops across the straits to help the governors of al-Andalus regain control. They crushed the uprising after a series of ferocious battles culminating in the Battle of Aqua Portora in August 742. However, the prejudice between the haughty Syrian commanders of the occupation, and the original Arab al-Andalus governors erupted in another uprising, which was put down in 743 by the Syrians led by the new governor of al-Andalus, Abū l-Khaṭṭār al-Husām.

Caliph Hisham’s army was drawn from far-flung parts of his caliphate and were organised into junds under their regional commanders, so al-Ḥusām assigned each of the junds a region to administer. The Egypt jund was split and given Tudmir (Murcia) in the east and Beja (Alentejo) in the west. The Jordan jund, Rayyu, (Málaga and Archidona). The Damascus jund was established in Elvira (Granada). The Filastin jund, Medina-Sidonia and Jerez. The Emesa (Hims) jund, Seville and Niebla and the Qinnasrin jund, Jaén. Instead of solving the problem of controlling of the new lands, it made things worse. The Regional commanders began a reign of autonomous feudal anarchy, severely destabilizing the authority of the governor of al-Andalus.

During this time of instability, the Berber garrisons holding the northern borders had deserted their posts to aid their brothers’ rebellion against the Syrians. The Christians in Asturias under their king, Alfonso I, swarmed out of the highlands and took control of the empty lands, quickly adding the provinces of Galicia and León to his kingdom. He evacuated the River Duero valley, bringing the people north within his kingdom and leaving a wide empty buffer zone between Asturias and the lands ruled by the Arabs.

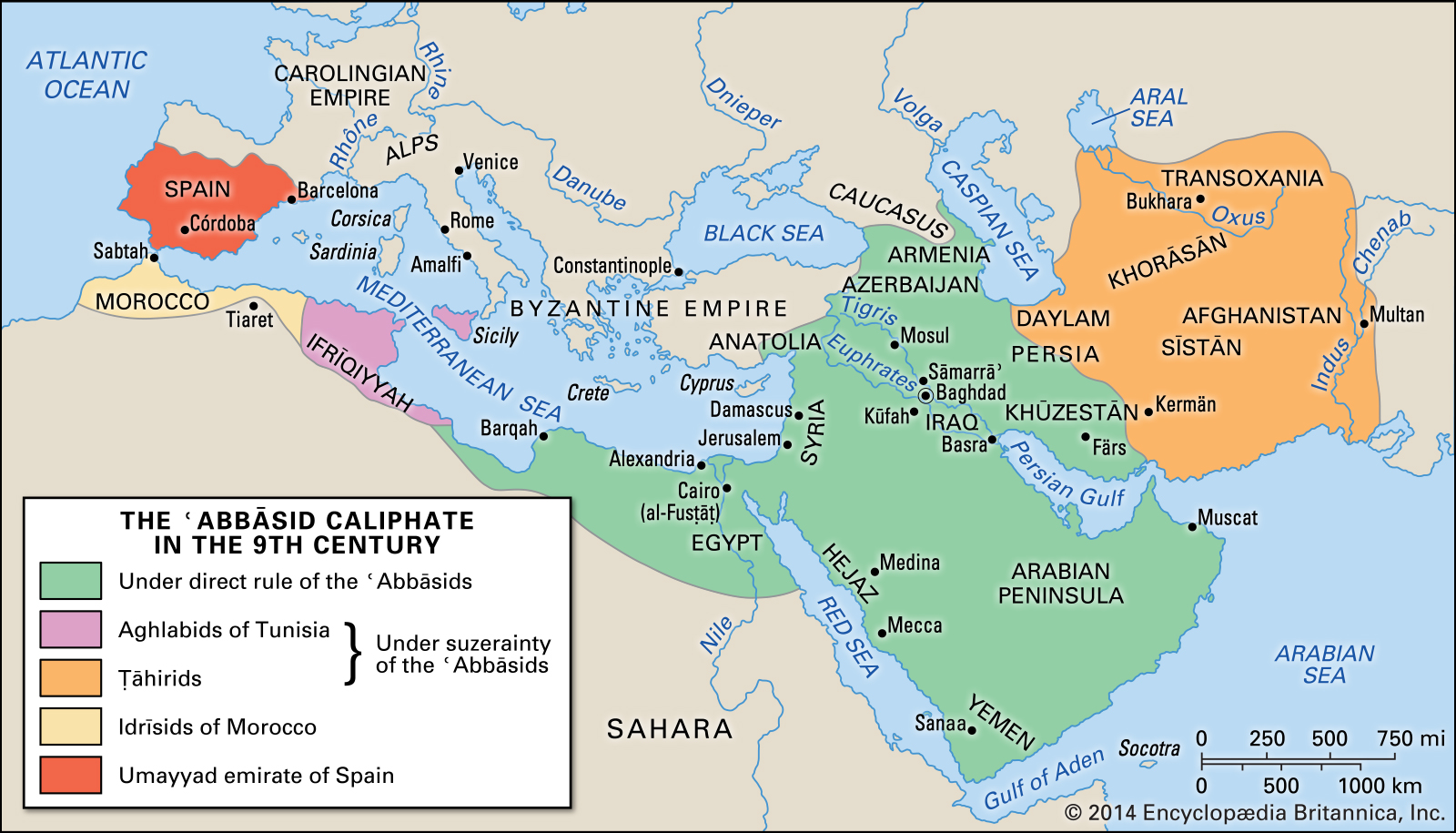

With al-Andalus practically out of control, the Caliph in Damascus found that he had other problems on his doorstep. The expanding Abbasid Caliphate was pressing on the eastern borders of the Umayyad Empire. The Abbasids were named after their founder, the uncle of the Prophet Muhammad Al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib. They eventually founded the city of Baghdad as their capital, and were a much more dangerous threat than the problems in Iberia. Caliph Hisham’s attention shifted eastwards, and Iberia was left to solve its own problems.

Map:Brittanica.

Map:Brittanica.

When the Umayyad caliph lost interest in al-Andalus, the opportunistic Fihrid Arab family seized power in the western Maghreb under Abd al-Rahman ibn Habib al-Fihri, whilst his son Yūsuf al-Fihri, took control of al-Andalus. The demise of the Umayyad caliphate allowed the Fhirids to seek an alliance with the Abbasids against them, but they rejected the offer and demanded that they submit to their rule. The Fihrid family defiantly declared independence from all outside control.

The war went badly for Hisham, and the Abbasids controlled all the Muslim lands by 750 creating thousands of homeless Umayyad refugees. In a generous gesture, the Fihrids welcomed them and allowed them to settle in al-Andalus. These were the sons and grandsons of Caliphs, and had a more valid claim to al-Andalus than the Fihrid family. They aligned themselves with the disenchanted lords under Fihrid rule and rose up against them. In 756, led by the Umayyad prince Abd al-Rahman I, overthrew the Fihrid family and the prince established himself as Emir of Córdoba. He held the title for thirty years despite his rule being challenged by the al-Fihri family and the Abbasid Caliph. His descendants ruled from Córdoba for another century and a half, though not always in full control of the many competing factions. It was al-Rahman III in 912 who elevated the caliphate to its greatest level restoring by Umayyad control over all al-Andalus and North Africa. He proclaimed himself Caliph of al-Andalus in 929 and his power was equal to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad and the Fatimid caliph in Tunis.

This period is now known as the golden age of al-Andalus. Orange and lemon trees had been introduced, along with and the cultivation of olive groves and pomegranate trees. Grain crops flourished in the rich soil, making the lands around Córdoba the most advanced agricultural area in Europe. Irrigation and the use of the water-wheel turned al-Andalus into a fertile paradise which in turn generated a rich economy and supported a growing population. Rice, coffee, coriander and basil were introduced as crops, and the working of metal for cutlery and ornaments. The working of glass became common, and ceramic glazed tiles reached a zenith in design and production.

This impetus of sufficiency generated a scholar class, and Córdoba became renowned as learning and teaching centre which was equal the universities of Italy. The libraries of al-Andalus grew in the major cities, and the ones in Córdoba alone held ten thousand books. Astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, games and music were encouraged, and though Islam forbade alcohol, they invented sherry and perfected its production. One of the founding pillars of the Islamic faith was the development of the mind, and Córdoba became the Versailles of Iberia.

With a population of around five hundred thousand people, Córdoba overtook Constantinople as the largest, most prosperous city in Europe, and its fame spread throughout the medieval world. The transmission of ideas generated by al-Andalus during the al-Rahman caliphates were like water to the seeds from which grew the European-wide Renaissance.

It was during the reign of al-Rahman III that the beautiful estate of Medina Azahara, meaning The Shining City, was built. This was a tour de force of opulence and majesty in the early medieval world. With ceremonial reception halls, offices, gardens, workshops and baths supplied by aqueduct with clear water and a barracks for the palace guards. Azahara was a self-contained palace.

Photo: By Wwal

Photo: By Wwal

The Shining City was extended during the reign of Abd ar-Rahman III's son Al-Hakam II between 961 and 976, but after his death it soon ceased to be the main residence of the Caliphs. In 1010 it was sacked in a civil war, and thereafter abandoned, with much masonry re-used elsewhere. It was a statement of power and wealth for the entire world to see and aimed at impressing his rivals in the Muslim world, the Ifriquian Fatmids and the Abbasids in Baghdad. The ruins were first excavated in 1910 and even now, only ten percent has been uncovered. There is a large cinema in the museum which gives the busloads of visitors a virtual reality tour of the city in its heyday.

Learning about the history of Spain is one of the themes of this blog and website, and one of the best ways to discover the past is to live there for a while. Medina Azahara is the setting for one of the 15 books of Joan Fallon. The shining City is set in this opulent epoch, and tells a story of love, family, and the choices that face ordinary people during difficult times.