A hundred and fifty-two years after the cathedral in Siena received its altarpiece, and 30 years before Leonardo was commissioned to paint his Last Supper, the Leuven Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament were in the process of building a new church which eventually became known as St. Peter's Church. They commissioned an Altarpiece from a 49 year-old Flemish painter called Dieric Bouts, who had moved to Leuven 13 years earlier.

Bouts may have studied under Rogier van der Weyden because his work shows that he was certainly influenced by him and Jan van Eyck, both leading innovators in the Early Netherlandish style typical of Bruges and Ghent. Dieric was from Haarlem, as was the architect of the church, Antoon I Keldermans. Both had probably been recommended by the church leaders in Haarlem, where they had achieved some fame for their work. The Last Supper was to be the central part of the altarpiece of the new church and was to become the first ever Flemish panel painting of the Last Supper.

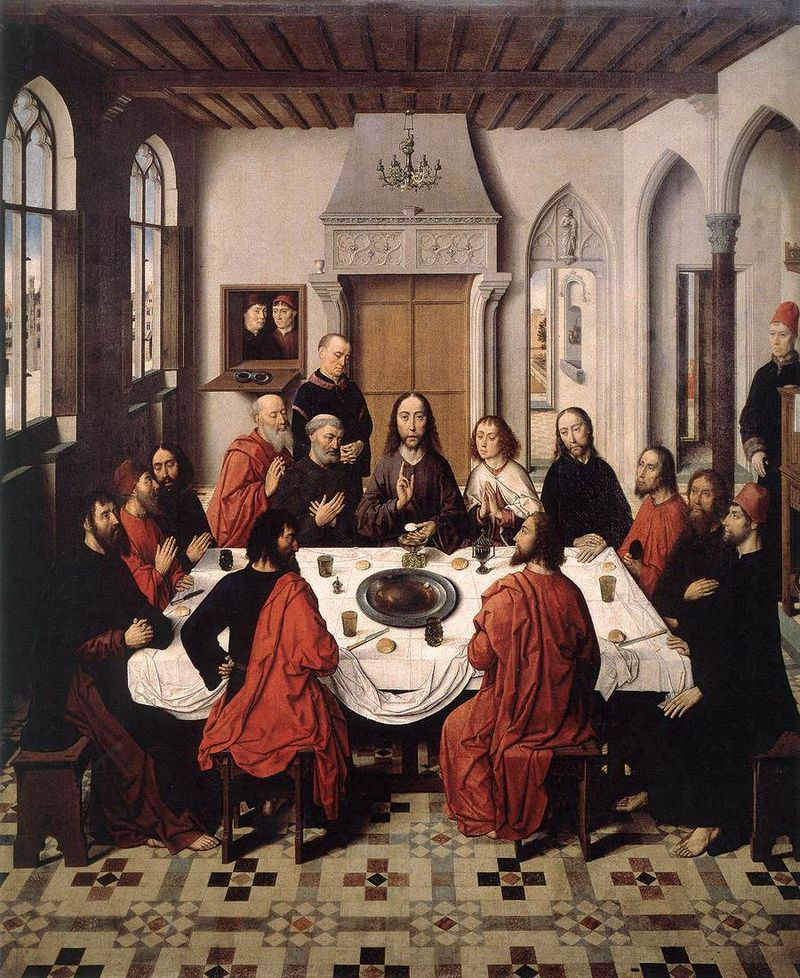

The central panel showing the Last Supper

However, the commission came with a long list of conditions. The Confraternity did not want the accepted scene of Christ’s revelation of betrayal; they wanted Christ in the role of a priest performing the consecration of the Eucharistic host from the Catholic Mass. Moreover, the two servants and some of the people who would have been painted as apostles were in fact portraits of local businessmen dressed not in the vogue of Jerusalem at the time of Christ, but in mid fifteenth century Dutch attire. To keep attention on the face of Jesus, the head of Christ is painted one-third larger than all the other faces, yet his face and some of the disciples are painted in a flat stylistic manner. However, those who paid to be included have quite good likenesses. Adding to this flagrant self-aggrandisement, the two faces in the serving hatch were the two priests who controlled the purse strings of the Confraternity, and who probably commissioned the painting. This just goes to show that even if you are a nondescript tradesman in a small town, you can elevate yourself to near martyrdom by buying an invite to Christ's last supper with his disciples.

Dieric’s painting of the Last Supper is also famous for its perspective, or to be more accurate, the mistakes in its perspective. Dieric was a student of Italian linear perspective, but he wasn’t too good at it. All the lines in the room should come to one vanishing point and Dieric decided to put his vanishing point in the middle of the lintel over the strange panelled doorway behind Christ. This high vantage allows you to look down on the table so that you can clearly see everybody sitting around it. But looking through the windows and open door, the horizon, which should also run through the vanishing point, is well below it. The side room on the right has a different vanishing point somewhere else, and the general effect is that of an architectural drawing rather than a work of art.

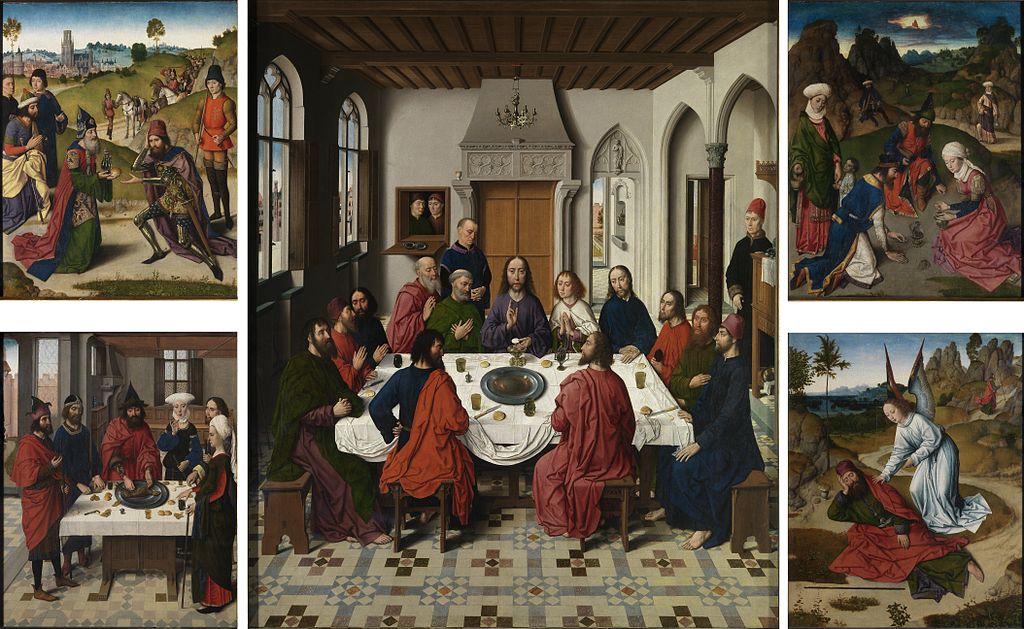

The panels shown in their original order.

Nevertheless, the full Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament, as shown above, remained in St. Peter’s church, Leuven, until the late 1800’s, by which time the art world had lost interest in the early Dutch painters, and some of the side panels were sold to an antiques dealer in Brussels. They later turned up in the museums of Berlin and Munich. Shortly afterwards, the First World War swept across Europe, and when the carnage was over, the negotiators at the Treaty of Versailles demanded that Germany should return the panels to Leuven free of charge in reparation for the war.

And there they stayed until 1942, when the altarpiece was removed once again and taken to Germany. This is when life got really interesting for the Leuven Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament.

When he became Reich Chancellor in 1934, Adolf Hitler had a dream of creating an art gallery in Linz, his home town. He wanted Linz to overshadow Vienna, where he had spent some unhappy years as a struggling artist. His dislike of the city stemmed not only from its strong Jewish influence, but because of his own failure to gain admission to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts.

Adolf is quite rightly vilified for his many other faults, but he initially established a fund from his own money to buy artwork to put in his proposed gallery. He used money from the sales of his book, Mein Kampf, profit from several property speculation deals, royalties from his image used on postage stamps and state birthday presents in the form of artwork. After a state trip to Rome, Florence and Naples in 1938 he was “overwhelmed and challenged by the riches of the Italian museums.” Hitler sent Heinrich Heim, one of Martin Bormann's adjutants, who had expertise in paintings and graphics, on trips to Italy and France to buy artworks.

After the Anschluss in March 1938, which brought Austria into the German Reich, both the Gestapo and the Nazi Party went on a spree of looting numerous artworks for themselves. Hermann Göring was chief culprit, and many of the purloined pictures ended up in his hands. In response, on 18 June 1938, Hitler issued a decree placing all artwork that had been seized in Austria be placed under the personal prerogative of the Führer. The order was to guarantee that Hitler would have first choice of the plundered art for his planned Führermuseum, and this later became a standard procedure for all stolen or confiscated art and became known as the Führer-Reserve. Because he was Hitler’s second in command, Göring was given control of the ERR, (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg für die Besetzten Gebiete) or The Reichsleiter Rosenberg Institute for the Occupied Territories. But when he thought Adolf’s men weren’t looking, he used it as his personal looting organization. At its peak, Göring’s art collection included 1,375 paintings, 250 sculptures and 168 tapestries.

On 21 June 1939, Hitler set up the Sonderauftrag Linz (Special Commission Linz) in Dresden and appointed Hans Posse, director of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Dresden Painting Gallery), as a special envoy. Hitler gave Posse a letter which ordered all Party and State services to assist him. By December 1944, Posse had spent 70 million Reichsmarks (equivalent to 261 million 2017 euros) on accumulating the collection intended for the Führermuseum. The acquisitions amounted to "technical looting," since the Netherlands and other occupied countries were forced to accept German Reichsmarks, which ultimately proved worthless.

Hitler's proposed art museum in Linz.

The artworks that Hitler collected were stored in a number of places, mostly in the air raid shelters of the Führerbau in Munich. But Göring's ERR had selected several estates for storage that were remote and unlikely to be bombed by the Allies. In 1943 Hitler ordered that these collections be moved. Beginning in February 1944, the artworks were relocated to the 14th-century Steinberg salt mines above the village of Altaussee, code-named “Dora” The transfer of Hitler’s Linz collection to the salt mine took 13 months to complete, and utilized both tanks and oxen when the trucks could not navigate the steep, narrow and winding roads because of the winter weather. The final convoy of art arrived at the mine in April 1945, just weeks before VE day. The salt mines usually had a single entrance, and a small gasoline-powered narrow-gauge engine was used to navigate to the various caverns. Into these spaces, workmen built storage rooms which boasted wooden floors, racks specifically designed to hold the paintings and other artworks.

In April 1945 Eisenhower gave up Berlin as an objective that would not be worth the troops killed in order to take it. He ordered the Third and Seventh Armies to turn south, towards what the Allies feared might be an "Alpine Redoubt" from which Hitler or fanatical Nazis could operate a guerrilla campaign.

From early on in the war, George Stout, a first World War Veteran working at Harvard's Fogg Museum, had been campaigning for a commission to be set up to catalogue the artwork that he knew was disappearing. American and British authorities were, needless to say, too busy with the war to listen. But in December 1944, the Allies created the Monuments, Fine Arts, and archives program. (MFAA) Stout was in the Navy working on aircraft camouflage, but was transferred the small corps of 17 “Monuments men” who were charged with cataloguing and recovering the missing artwork. They began to follow clues which led them all to locations in the area that Eisenhower had chosen to liberate last.

Captain Walker Hancock, the Monuments officer for the U.S. First Army learned the locations of 109 art repositories in Germany east of the Rhine by interrogating the assistant of Count Wolff-Metternich of the Kunstschutz. Captain Robert Posey and Private Lincoln Kirstein, who were attached to the U.S. Third Army, questioned Hermann Bunjes, a corrupted art scholar and former SS Captain who had been working for Hermann Göring’s ERR. Their information led them to Heilbronn, Baxheim, Hohenschwangau and Neuschwanstein Castle, where much of Göring’s loot was hidden. 1st Lt. James Rorimer attached to the U.S. Seventh Army had made contact with Rose Valland, a French resistance worker, who eventually shared the trove of information she had gathered at the Jeu de Paume museum while Göring’s ERR were using it as a store for stolen art.

The Monuments men.

The Monuments men.

The gathering of the Monuments men became a frantic race when Hitler issued his Nero Decree shortly before the Russians overran Berlin. It called for all works of art to be destroyed in the event of his death or Germany falling to the Allies. Seemingly, Hitler had second thoughts about his decree and countermanded it, but after his suicide, the interpretation of his decree was left to officers in the field. August Eigruber, the Gauleiter of Upper Austria, had placed eight crates of 500-kilogram bombs amongst the artwork in the mine tunnels and he gave orders that they be wired and detonated.

The managers of the mine argued that the mine was their livelihood, and tried to remove the bombs. They were forced out of the mine by the Gauleiter’s troops who stood guard at the entrance whilst a demolition team set the charges. With the Americans just a few miles away, Eigruber fled with an elite SS bodyguard leaving his troops to finish the job.

Dr. Emmerich Pöchmüller, the general director of the mine, Eberhard Mayerhoffer, the technical director, and Otto Högler, the mine’s foreman approached Ernst Kaltenbrunner, an SS officer of high rank in the Gestapo who had grown up in the area and persuaded him to countermand Eigruber’s orders. They also persuaded the mine guards left by Eigruber to allow them to re-position the bombs so that they sealed the tunnel entrances without damaging the artwork inside. The plan took three weeks to execute, and on 5 May the charges were detonated. The Americans and the Monuments men arrived on the 8 of May and, aided by the mineworkers, frantically began clearing the entrance and bringing out the artwork. They removed the last pieces just before the Russians arrived.

If you haven’t seen the 2016 film, Monuments Men, you should watch it.

To finish the story, Dieric Bouts’ Last Supper was returned to Leuven when the war ended, and that’s where it remains to this day.