Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola was a Spanish jurist who owned lands around Santillana del Mar in Cantabria. He was also an amateur archaeologist, and when one of the local hunters, Modesto Cubillas, told him of a cave on his land his interest was piqued and he decided to go and look for himself. The cave had been known to local people for years, but Sautuola began a series of visits starting in 1875 during which he explored the cave system. On one of these visits his eight-year-old daughter, Maria, accompanied him, and it was she who first saw the shadowy form of pictures on the ceiling of the cave. She excitedly told her father who brought trestles on their next visit so that he could examine the ceiling more closely.

Maria Sans de Sautuola.

Maria Sans de Sautuola.

He was amazed to find that the ceiling was covered in paintings of bison. Sautuola had seen similar images engraved on Paleolithic objects displayed at the World Exposition in Paris the year before, and he rightly assumed that the paintings might also date from the Stone Age. This prompted him to write to Juan Vilanova y Piera at the University of Madrid, who immediately travelled to Santillana del Mar to see the find for himself. During 1879 they explored the cave together and the following year published a scientific paper proposing that the paintings were Paleolithic in origin.

Sautuola´s drawing of the paintings.

They presented their paper at the 1880 Prehistorical Congress in Lisbon, but they met instant opposition from two French specialists on prehistoric art, Gabriel de Mortillet and Émile Cartailhac. Most of the known cave paintings in Europe at that time were in a small area alongside the river Dordogne, the most famous, of course, being Lascaux. The Frenchmen examined the cave for themselves, and at the congress they ridiculed the findings of Sautuola and Piera. Because they were de-facto the only experts in a very limited field, their opinion carried a lot of weight.

Cartailhac rejected the paper because of the high artistic quality of the Altamira paintings and their exceptional state of conservation. He called attention to the fact that there were no soot marks that would be unavoidable for a prehistoric painter who was using tallow lamps for illumination whilst painting a ceiling. To add to the condemnation of Sautuola and Piera’s paper, a fellow Spanish archaeologist accused Sautuola of paying an artist to paint the bison, and that the whole thing was a fraud. Sautuola, with his limited experience, could not defend the accusations, and it was only years later that he learned that many of the Paleolithic painters used marrow fat in their lamps because it doesn’t give off smoke or soot.

The damage was done, and Sautola’s find was ridiculed and rejected by mainstream archaeology. Sautuola died in 1888, but the science of archaeology moved on, and later finds at other sites corroborated his findings. In 1902 the scientific society retracted their opposition to the Spaniard’s paper. Cartailhac emphatically admitted his mistake in the famous article, “Mea culpa d'un sceptique” published in the journal L’Anthropologie.

With the authenticity of the cave verified, the archaeological spadework began anew. The relatively flat ceiling in the cave entrance is where the majority of artwork is to be found, though more can be found in the twisting passages and chambers deeper within the cave. It was discovered that the cave was occupied during two distinct phases: the first ended 18,000 years ago, and the second is between 16,600 to 14,000 years ago. In between, there is a 2,000 year gap when it was not occupied by humans at all. Sometime around 13,000 years ago a rock-fall sealed the cave entrance until modern times. It was only discovered again when a tree fell and the roots dislodged some rocks revealing a cavity beyond.

The artists used charcoal and ochre for their paintings and had used the natural contours of the cave walls to give a 3-dimensional effect to their painted figures and by far the most impressive and famous group are the herd of steppe bison, a long extinct species. There are other animals, too. Two horses, a large doe and a wild boar, all painted with the same vivid colours that the artist must have seen with his own eyes. French cave art takes first prize for its variety of animals and the quality of artwork, which in fact, is beyond the ability of most modern people, and to be honest, many modern self-acclaimed artists. But the question that has puzzled archaeologists is why they were painted at all.

Photograph of the steppe bisons

Although petroglyphs or engravings on the walls of human occupied caves had been found which have been dated at around 44,000 years old, full colour and form rock painting burst into human culture around 25,000 years ago. Archaeologists sometimes call this the “the day we learned to think”. Cave artwork began during what is called the last glacial maximum, (LGM) the coldest part of the last Ice Age. The artwork is not religious; there are no demons or deities in any of the pictures. Later paintings have drawings of stick men with bows and arrows and sometimes rows of scratches that could be a calendar, so what was the reason for the explosion in cave painting?

Humans at this time were all hunter-gatherers. Farming was around 14,000 years in the future, so to survive, these hunters needed to work together as a pack to hunt the food they needed. Family groups could not hope to feed themselves with just two or three hunters. The herd of bison shown at Altamira would most likely be animals that migrated seasonally through northern Spain, and like so many of the Ice Age animals, they were big. The steppe bison weighed in at around a ton and had horns that measured a meter across. The Aurouch, ancestor of modern cattle, also weighed about a ton and was about twice the size of a modern bull, standing seven feet tall at the shoulder. However, for the northern latitudes, the mammoth took first prize for size at ten feet tall and weighing around six tons. It needed organized teamwork to bring down one of these animals with just flint tipped spears, and one recent theory is that the paintings were a visual aid for more experienced hunters to show the young novices how to go about it. This may be true, but the quality of the paintings goes far beyond the simple line diagrams needed, and it may be that although simple drawings would have sufficed, the chance to show off with full colour pictures of the hunt was more than the artist could resist. What started off as a tutorial turned into an exhibition of the new suite of abilities that modern humans were to develop in time. Human cave painting of animals took place over a span of 20,000 years, and was the longest-lasting culture in human history. It endured for 800 generations and stretched from southern Spain to the Urals. But once the ice retreated and the forests returned, bringing smaller game like deer and boar, the caves were abandoned and cave art stopped.

_Credit_H. Collado.jpg_SIA_JPG_background_image.jpg)

Close up of hand stencils believed to have been painted by Neanderthals.

But humans were not the only hunter-gatherer inhabitants of Iberia during the Ice Age. Neanderthals predate the arrival of modern humans in the area and they also had a more primitive form of cave art that began 64,000 years ago. There are several sites in Spain where you can see their work. The Cave of Maltravieso in Cáceres, Extremadura, contains 71 hand stencils, some of which are from around this time.

But by far the best places to see how Neanderthals lived is at Ardales in Málaga province. The artwork that they left can hardly be called art compared to later humans and is limited to simple symbols rather than animal or human forms, but it is 40,000 years earlier than later cave paintings made by Homo Sapiens. Nevertheless, it represents the first stirrings of a new consciousness that was to transform the world.

Altamira is a long hike from Andalucía, but the centre has related displays with bi-lingual explanations and is well worth the visit if you tie it in with other places of interest and make a holiday of it. The real cave has been closed to visitors since 2002 because mould was found to be destroying the original paintings. A replica cave and museum were built nearby and completed in 2001 by Manuel Franquelo and Sven Nebel, reproducing the cave and its art.

Ardales is much easier to reach and has almost as good a display as Altamira with a section dedicated to the Neanderthals. Also, you can visit the beautiful village of Ardales and the ruins of its Moorish castle on a promontory above the pueblo. (The name Ardales is from the Arabic Ard Allah, meaning God’s country.) But, of course, the real attraction at Ardales are the embalses, which gives the area its other name, the Lake District of Málaga Province.

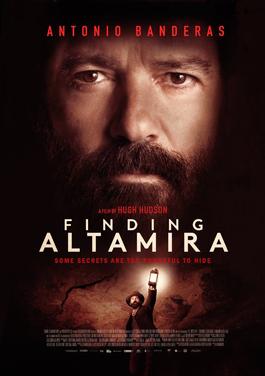

Just to finish off, little Maria who discovered the bison at Altamira married into the rich Botín family, and her children and grandchildren are among the current owners of Banco Santander. There is also a film starring Antonio Banderas called Finding Alatamira.