It is a quarter to ten on Saturday morning in the port of Lisbon and many people are arriving at the weekly market held in the plaza by the docks. Fish caught that morning and vegetables brought in from the farms will be on sale, along with fruit, dates and spices. The early risers will have already bought the best fish and are pushing through the noisy stalls looking for something to go with it for the evening meal. White linen canopies protect the stallholders and their goods from the warm morning sun, and children run between the shoppers calling to each other and laughing.

Suddenly the earth beneath the feet of the people moves so rapidly that they are thrown to the pavement. Stalls collapse, and fruit rolls amongst the people on the ground who are trying to scramble to their feet. Many have managed to stand only to have the earth move again in the opposite direction, and once more they tumble to the floor. So far this has been soundless apart from the screams and cries of the people, but now a rumble turns into a roar as the buildings around the plaza collapse upon the market stalls, burying them in masonry and rubble. It is All Saints day, and many of the houses and churches had lit candles, and as the buildings collapse, the flames of the still burning candles ignite spilt oil, which soon spreads to the bone-dry timbers of the fallen buildings and their furniture. The earth is still moving, and the next heave opens a fissure across the plaza three meters wide. Fruit and people roll into the chasm and those around the edges scramble away in terror as the earth continues to shake. For five minutes the earthquake continues before stopping. Now, the only sound is that of the wails of the injured and the screams of those who are terrified.

Many who fear more tremors push through the crowds, scrambling over the rubble and bodies, ignoring the cries of those who are trapped. They elbow their way to the open area of the docks and are amazed by what they see. The sea is leaving faster than any tide that they have ever seen. Wrecks and rocks never seen before appear as the sea retreats, and ships that had been riding at anchor are left high and dry and slowly roll over onto one side.

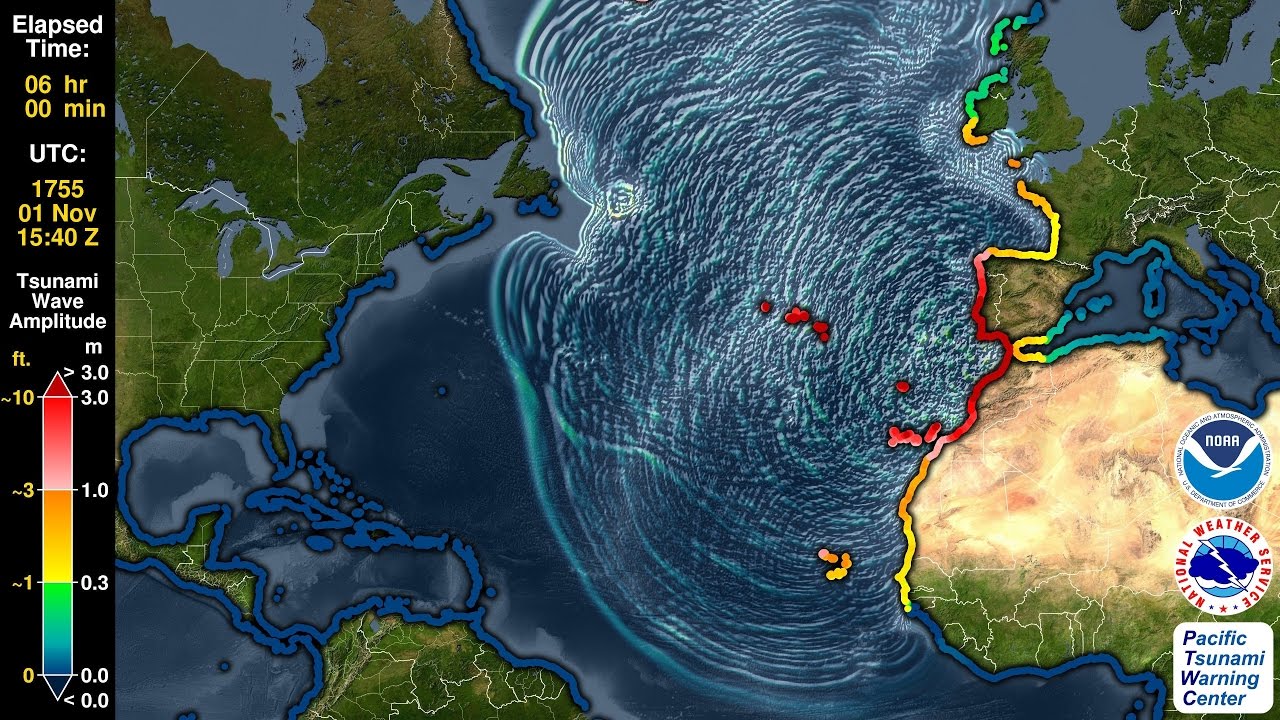

The fires in the rubble and remaining buildings are growing in intensity and more people run into to the open areas. Those on the seafront stand shocked and speechless at the spectacle of burning and collapsed houses as far as their eyes can see. But their attention is soon drawn to the seaward horizon by the low roar of the returning ocean. A tidal wave three meters high is rushing towards them, lifting ships and tossing them over as though they were toys. It crashes over the low seawalls and surges through the city. The water subsides, but the fire rages on creating a firestorm that draws the oxygen out of the air, suffocating hundreds of people before they can flee. More waves crash over the sea walls, but the fire is unstoppable and continues burning for weeks after the earthquake.

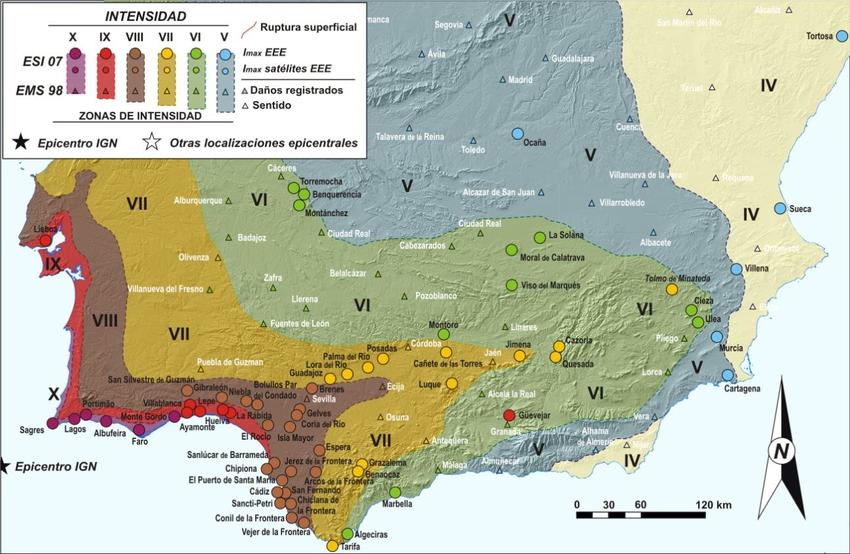

This was the Lisbon earthquake of 1577, and when the fires had burned themselves out it was estimated that between30,000 and 50,000 people had been killed; one fifth of the population of the city. Eighty five percent of the city’s buildings had been lost, along with priceless artworks and libraries. It was not just Lisbon that suffered; the western coasts of Andalucia and Morocco were devastated by tremors and the following tidal wave. Spain’s primary Atlantic port of Cádiz was almost totally destroyed as the tidal wave entered the port, became focused, and roared across the surrounding low-lying areas. The earthquake caused damage to buildings far inland, and the Alcazar in Seville was found to have cracks in its foundations which required major building repairs.

But the 1577 earthquake was not the only one. It was just the biggest and best documented one out of a known total of four. After the 1755 earthquake the Marquis of Pombal, the Portuguese Secretary of State for Internal Affairs, was given the job of rebuilding Lisbon and the Portuguese economy following the earthquake. In an effort to better understand his task, he asked one of his deputies to look through the records and see how previous governments had dealt with earthquakes. His search gave details of the earthquake that had occurred in the early morning of January 26, 1531, which had been preceded by two foreshocks on the 2 and 7. Again, damage to the port of Lisbon had been severe, with around one-third of the buildings in the city destroyed and 1,000 lives lost. Before 1577, earthquakes were believed to be “Ira Dei”- the wrath of God, but the investigations started by Pombal led to the birth of modern seismology and the understanding of earthquakes. In the end, the Marquis of Pombal rebuilt Lisbon hoping that it was over, but 184 years later disaster struck again.

On the afternoon on March 31, 1761 there was another earthquake causing widespread damage across Portugal, Spain and Morocco. Although not as strong as the 1577 earthquake, the effects of this one were felt throughout Western Europe as far north as Fort Augustus in Scotland, at the southern end of Loch Ness. There, fishermen noted a sudden two-foot high rise in the lake level which lasted just less than an hour before subsiding again. Simultaneously, Cork in Ireland recorded “strong shaking” that lasted several minutes.

The final link in the chain came in 1909, when a Portuguese newspaper reported the discovery of an unsigned manuscript of eyewitness accounts of an even earlier earthquake in 1321. This report was corroborated in 1919 by the discovery a four-page letter found in a Lisbon bookshop addressed to the Marquis of Tarifa describing the1321 event. It was clear now that the 1577 earthquake was the biggest, but only one of four earthquakes to shake Portugal and Spain. Earthquakes on this level of destruction seemed to have been occurring around every 200 years since records began.

Now, of course, we are in possession of much more information to help us understand what forces cause earthquakes. Off the coast of Spain, the Atlantic sea bed is relentlessly moving east at 3.8 mm a year, giving rise to a series of strike-slip and thrust faults collectively called the Azores-Gibraltar Fault. The epicentre of the 1577 earthquake was along a 50-kilometer fault some 200 kilometers south of Lisbon, The unstoppable eastward movement of the earth’s crust beneath the Atlantic makes it inevitable that there will be another earthquake like the one in 1577.

For Andalucia, the greatest risk to the population lies in the arc of coastline from Ayamonte in the north to Tarifa in the south. The earth tremors are likely to cause damage as far inland as Seville, but because of the low-lying nature of the coastline, the following tsunami presents the biggest threat to life. Areas of the coast that are substantially higher than sea level, and have cliffs facing the sea will be safe, but much of the coastline is low-lying with a high population density. Two main areas of this coastline have been designated as high risk from the tsunami. Huelva in the north, and the Cádiz bay area, including El Puerto Santa Maria, Chiclana, Sanlúcar de Barrameda and San Fernando.

Historical records and simulations have been combined to predict that the worst-case tsunami could be to be up to 7 meters high with a flow velocity of between 3 to 8 meters per second. If previous earthquakes are anything to go by, there may be several tsunamis after the earthquake, followed by more aftershocks.

Geologists have learned not to cry wolf too often. False alarms breed complacency which will get people killed when the real event arrives. The answer is to have regular drills and exercises so that everybody knows what to do, and it soon becomes apparent that time is the main factor in saving lives. Estimates vary on how long it will take for the tsunami to arrive after the earthquake. Huelva will be first to see the approaching wave and raise the alarm, but by the time that the warning reaches Cádiz and the alarms sounded the wave will be just 20 minutes away.

The Diario de Cádiz and the Vos de Cádiz have raised concerns that most of the population have no idea where nearest safe areas are, or what precautions to take. There is no recognised alarm system for people who work and live in these areas. They go on to say that every family should know where to go to be safe. Schoolchildren in Cádiz have regular drills in which they leave school and walk to the nearest high rise building when the alarm is given, but there is no plan for their parents or grandparents. An even greater worry, are the huge numbers of holidaymakers who fill the beaches every summer weekend. They will have no idea of how to go about the “vertical evacuation” that the gaditanos have planned.

The Junta de Andalucía and the Diputación y el Ayuntamiento de Cádiz have drawn up emergency procedures for medical, security and the restoration of infrastructure after the event, but they have little to say about what measures can be taken to save lives before the event. Some of the barrios have designated their own high-rise refuges, and neighbourhood committees in Cádiz have drawn up lists of basic measures that householders can follow. Immediate loss of electrical power, roads blocked by fallen buildings and the destruction of most vehicles is inevitable, so the storage of emergency first-aid supplies and large amounts of bottled water are a must. The medical, rescue and fire services will be stretched to the limit, and aiding the injured and homeless survivors will require mobilisation on a national scale.

In built up areas the buildings have been assessed for their survivability in a major earthquake. Overhangs, balconies, glass roofs and fasciae will go in the first few seconds. Conventional stone and mortar may not survive a prolonged earthquake, but steel-reinforced concrete buildings might, and if they are multiple-story, could become refuges from the tsunami. The risk of fire is a major problem. With most homes using bombonas for heating and cooking, the puncture or cutting of rubber tubes could release highly explosive and inflammable gasses into partially collapsed buildings and hinder rescue attempts even when the water has subsided. Equally, the storage sites for bombonas and the tanks of petrol and diesel beneath most gasolineras are the subject of much concern.

To make people aware of the danger of the tsunami, La Sexta have produced a virtual video of what can be expected in Cádiz. The only thing missing from the video is the thousands of people in the streets who were too late to get to the third floor and safety.

https://www.diariodecadiz.es/vivir_en_cadiz/Sexta-video-maremoto-Cadiz_0_1581744059.html