The north of Iberia had evaded the Islamic invasion primarily because of its mountainous terrain, which afforded the Christian defenders a wealth of hiding places and ambush traps for invading troops. Also, in winter, many of the high passes were closed by snow, and there were easier gains for the Moors and better pastures in the lowlands. The Romans thought pretty much the same, and they left the north west of Iberia alone, too. In fact, the Romans had called Galicia the “finis terrae” or the end of the world. To them, the Atlantic Ocean stretched off into infinity, and they believed that Galicia was where the souls of the dead rested before making the long journey to the afterlife. The encirclement by the Moors served to concentrate those of the Christian faith and strengthen their traditions and folklore. They were isolated, whilst Islam dominated most of Iberia and the holy land, the home of their faith. The future looked pretty bleak for Christians, and they needed something to rally around closer to home.

The Moorish forces led by Musa ibn Nusayr had already swept past the old kingdoms. Abd al-Rahman I took control of Arab forces in al-Andalus in 756 and consolidated his grip after his coup. The kingdom of Asturias was the strongest force in the Christian zone, and when its king, Alfonso I, conquered León and Galicia in 754, it became a safe haven for all the dispossessed Christians from the south. It was Alfonso who created the Desert of the Duero, a depopulated buffer zone between Muslim and Christian lands, so that invading armies would have to carry their supplies instead of looting them, and it was Alfonso who began the enormous task of taking back those lands that the Moors had captured.

The first mention of Santiago was in a poem or song written around 783, but little is known about it. The name itself is a hint. Saint James in Vulgar Latin is, Sanctus Iacobus, which, when corrupted by the local Galician dialect Comes out as Santiago. St. James was beheaded in Jerusalem the year 42 on the orders of Herod, and the legend tells that his body was transported from the Holy Land to Galicia in a miraculous ship made of stone. Most historians consider this to have been a local home-grown legend.

It was during the reign of King Mauregato, around 820, that the legend gained momentum. In a hermitage called Peleo in the forest of Libradón, a group of devotees saw miraculous lights in the sky which seemed to fall to earth over a hillock in nearby woods. When the abbot of the hermitage reported this to his bishop, Iria Flavia, the bishop told his superior, Teodomira, who came with an entourage of clerics to witness the events for himself. Over a number of nights, they all watched the stellar display. They cleared the forest over the hillock and began excavating and soon found a stone sepulchre containing three bodies. Teodomira immediately rushed away to tell King Alfonso II about the miracle that he had seen and the bodies that he had found.

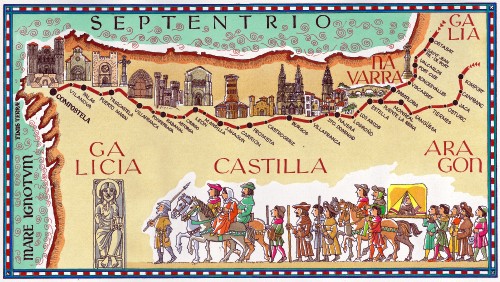

Alfonso was a shrewd king, and he saw the potential for a god given icon that his armies could unite under and fight for. He ordered the bishop to build a small church next to the tomb and use this as his seat of office. It was to be called Compostella, from the Vulgar Latin for burial ground, compostia tella, though there is another theory that the name is derived from campus stellae, “field of the star” but this is an unlikely corruption from Latin to medieval Galician. Whatever the name, it attracted the devoted in their droves, and they made pilgrimages to see the tomb of St. James from all four Christian kingdoms and as far away as Gaul. Coincidentally, Alfonso led several successful campaigns against the Moors after the discovery, which gave weight to the idea that St. James was aiding the Christians.

This is where the truth becomes entangled with myth. Alfonso died in 842 and his successor, Ramiros I, continued the fight against the Moors. According to the legend, Emir Abd al-Rahman II demanded a jizya (a tribute) of 100 virgins, and Ramiros refused to comply. This resulted in the two armies supposedly meeting at Clavijo, where the Christians were outnumbered, but fought valiantly. Before the battle began, Ramiros prayed for victory, promising to give a part of the booty from the battle to the hermitage of Santiago, along with the first fruits of the harvest each year.

St. James Matamoros, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

St. James Matamoros, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

In truth, neither Christian nor Moorish records contain any mention of the battle. The legend was first written down about 300 years after the supposed event. Another embellishment that was added to the fictitious battle at an unknown date was that at the peak of the battle, when defeat seemed imminent, some of the soldiers reported seeing a vision of St. James on a white horse brandishing a raised sword leading them to victory. The year and date of the conflict is different depending on which account you read, and the history of the cult of Saint James is rich in such errors. But it doesn’t matter if it was true or not; the Christians had an icon to follow. The reconquesta continued, but what had been a war of conquest for gain through looting and slavery had become a religious war.

This was not lost on the leaders of the Muslim caliphate in Córdoba. The Shining City was nearly complete, but its penultimate patron, Emir Al-Hakam II, died in 976 and Hisham II became the ruler of al-Andalus. Hisham was a child when he took over a civilisation that was at its peak, and his regent, al-Mansur, who was caliph in all but name, took control. After around 200 years of nearly constant incursions the caliphate from Asturius, al-Mansur decided to take the battle to the Christians. This was not altogether a religious or ideological assault, though he knew as well as the Christians did that the symbolism of a strike deep into Christian lands would bolster his support.

The cost of building Madina al-Zahira, and the bribes in land and gold that he had to give in order to maintain his position as caliph, plus the rising cost of the army that he needed to defend his northern borders required that he raise some money from somewhere, and the growing prosperity of the Catholic Church and the population of the four northern Christian kingdoms were a possible source.

Over the next twenty years, he made around 56 assaults during 9 campaigns on the kingdoms, primarily to deter and weaken the Asturian king, but also to return with as much booty as his troops could carry. In modern day values, they were little more than well organised bank raids.

One of them was on the church of Santiago de Compostella, which had grown over the centuries to be a rich area by virtue of the peregrinos, who had brought what was in reality medieval tourism into the area from Northern Iberia and France. The caliph’s troops would never have found the church had it not been for their hired Christian mercenaries who led him to the town. According to history, the caliph rode his horse into the church and allowed it to drink holy water from the font. The captive Christians of Santiago could only watch in horror as he ordered the church burned to the ground.

Hisham’s troops found little of real value, but the church had expensive cast bells in the belfry. They were removed and carried the 860km back to Córdoba, where they were melted down and cast into lamps to be hung in the Great Mosque. Two and a half centuries later, in 1236, the Castilian King, Ferdinand the Third ("The Saint") reconquered Córdoba. His first action was to avenge the humiliation caused by Al-Mansur. He had the lamps carried back to the shrine of Saint James, where they were melted down again to make a new set of bells.

The not so golden age of al-Andalus was coming to a close, and the turn of the century would see the beginning of a thousand years of religious intolerance and warfare. It was never really the peaceful Camelot that the wistful dream about, but it was a good try. By the end of the first century, Christian troops were blessed and said mass before going into battle to slaughter and loot. Popes, Bishops and even one of the disciples of Jesus would lead armies and carry a sword.

As a final irony, when the conquistadores invaded the Americas, they carried banners and icons of St. James Matamoros to rival the indigenous gods and to protect and sanctify the Spanish troops as they robbed the entire continent of its gold and enslaved or murdered the population.