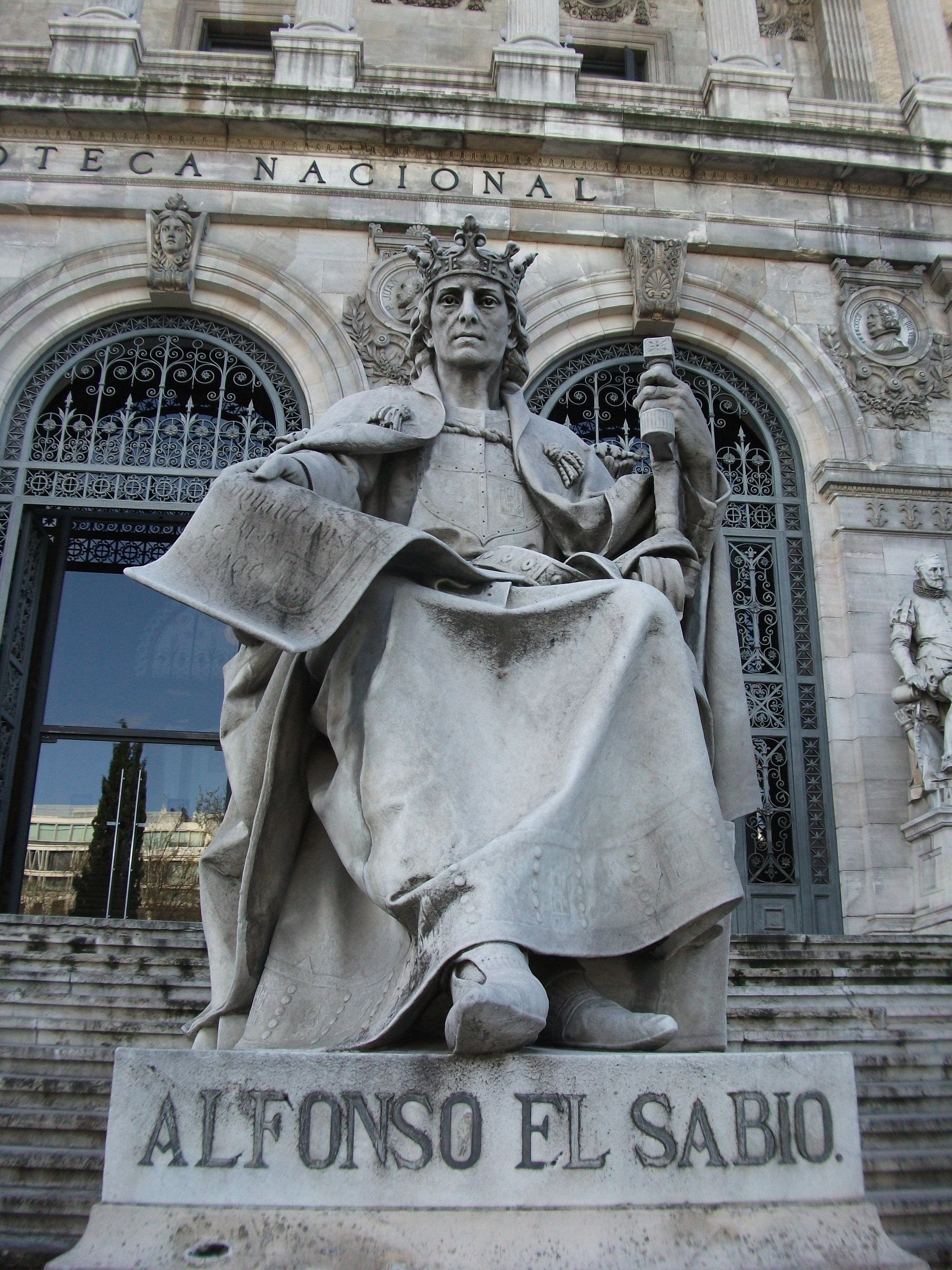

After the capture of so much land from the Moors, the Kingdom of Castile struggled with the repopulation, control and financing of its much enlarged domain. This task fell on the shoulders of King Ferdinand III’s son, Alfonso. King Alfonso X of Castile and León was called “El Sabio” (the wise), but there are two sides to King Alfonso. If you measure his reign in battles won, then he would be a failure. If you measure him as a diplomat, who ruled a peaceful country, then he would fail again. But if you measure him as a visionary lawmaker, writer and scholar, who fostered enlightenment in the dark ages, then he earned his title of El Sabio.

The next round of wars between the Catholic Kings and the Marinid and Granadan caliphates would involve Alfonso X and his sons, Sancho and John, but it would not go well for either side. For the next 200 years, little land would be gained, but hundreds of thousands of lives lost in wars of attrition as the moors tried to recover lost territory

At first, Alfonso was only heir to the crown of Castile, but his father united the kingdoms of Castile and León when he was nine, and he became the prince of two kingdoms. His training as a soldier began from the age of sixteen under the guidance of his father, and they fought together in several successful campaigns during which they took Murcia, Alicante and Cádiz from the Moors.

It was while he was serving in the army with his father, that young Alfonso was struck with the code of chivalry and mutual respect between knights. He soldiered with Perez de Castron, a friend of his father, and what the old knight taught him, and he subsequently saw for himself in battle, left a lasting impression on the young prince. He wrote later that during a battle to take Jerez, he had a vision of St. James mounted on a white horse holding a white banner in the sky above Castilian troops. This revelation appears to have formed his later opinions on law and the conduct of knights.

Prince Alfonso was not so pious when it came to the ladies. When Theobald I of Navarre was crowned, Alfonso’s father tried to arrange a marriage with Theobald’s daughter, but Alfonso had already fallen for Mayor Guillén de Guzmán, who bore him a daughter, Beatrice. The couple married in 1240, but they were forced to annul the marriage and Beatrice was declared illegitimate. During his lifetime he also fathered two other illegitimate children.

Nine years later, Alfonso, now twenty-eight, was married to thirteen-year-old years-old Violante of Aragon. For the first few years of the marriage, poor Violante was too young to be a wife, but after puberty, several years passed without any sign of pregnancy. Alfonso considered writing to the Pope asking to annul the marriage, but during one of the campaigns against the Moors in Alicante, legend says that the king and queen spent a few nights resting in a small farm in the countryside, and it was during their stay, she became pregnant with their first son, Ferdinand. A grateful Alfonso called the farm the "the plain of good sleep" or "pla de bon repos." Now a suburb of Alicante, it is still known by this name today.

In 1252, upon his father’s death, he was crowned King of Castile and León and his first act as king was to invade Portugal, forcing the greedy and avaricious King Afonso to surrender his kingdom. Clever Alfonso struck a deal with the Portuguese king, making him divorce his own wife and marry Alfonso’s illegitimate daughter Beatrice - or lose his kingdom. Poor Afonso had no option but to comply. This meant that Alfonso’s daughter would be queen of Portugal, and any children would inherit the crown of Portugal, but be allied to Castile and León.

But ambitious Alfonso came unstuck when he tried to lay claim to the biggest prize of all.

His mother was a daughter of Emperor Philip of Swabia, which meant that he was eligible to be King of the Holy Roman Empire. However, to be chosen, Alfonso needed to convince the prince-electors of the Vatican that he was worthy of the title. This usually involved lengthy negotiations and large-scale bribery. Alfonso had a rival for the title, Richard of Cornwall, and the prince-electors had a field-day playing the two off against each other. In the end, Richard of Cornwall was selected because Alfonso had supported people that Pope Alexander IV didn’t like. Richard went to Germany and was crowned in 1257 at Aachen, and Alfonso had to face the music at home.

To raise money to fund his claim for the throne of The Holy Roman Empire, Alfonso had debased the coinage of Castile and then endeavoured to prevent a rise in prices by an arbitrary tariff. The little trade that his dominions had established was ruined, and the burghers and peasants were deeply offended The mudejar uprising in 1264 was a rebellion by the Moors living in Castile who were unhappy with the unfair laws and increased poverty caused by King Alfonso’s taxation, but they were in part stirred up by the Granadan emir. The end result was the expulsion en-masse of the Moors from Castile.

The Marinids began to figure in King Alfonso's fortunes when they crossed the straits to occupy the old Almohad territories, But It was when Abu Yusuf Yaqub formed an alliance with the Caliphate of Granada that King Alfonso decided to take the war to Morocco, and sent a fleet of ships carrying troops to invade Salé in September 1260. The port was occupied for a short while, but Alfonso’s men were eventually repulsed. He tried to invade again in 1267 with a larger force, but his troops were once again driven out. Abu Yusuf decided that in order to protect his interests in Iberia, and to stop invasions on his own shores, he needed to take key ports on the southern coast of Iberia. Whoever controlled the straits would have the upper hand in fighting a war.

Abu Yusuf entered Marrakech in September 1269, putting a final end to Almohad rule. The Marinids were now masters of Morocco, and Abu Yusuf took up the title of 'Prince of the Muslims' (amir el-moslimin), the old title used by the Almoravid rulers in the 11th-12th centuries. However, the Marinids had some difficulty getting their authority recognized by the southerly Ma'qil Arabs of the Draa valley and Sijilmassa. The Draa valley Arabs submitted only after a campaign in 1271 and Sijilmassa only in 1274. The northerly city ports of Ceuta and Tangiers also refrained from acknowledging Marinid suzerainty until 1273.

Whilst King Alfonso had spent ten years and tens of thousands of maravadís in bribes chasing the crown of the Holy Roman Empire, he had also been foolishly meddling in the affairs of the Granadan Caliphate. With the encouragement of King Alfonso, the Banu Ashqilula family, rulers in Malaga, Guadix and Comares, had risen up against the young emir. To make matters worse, he had raised the tribute that the emir was forced to pay. Emir Muhammad II el Fagih had objected, but some of Alfonso’s disgruntled nobles had been making their own pacts with the emir, who was instigating his own rebellion against Alfonso. His nobles, whom he tried to cow by sporadic acts of violence, rebelled against him in 1272.

Finally, Muhammad sent the king a letter asking him to stop stirring up trouble in his caliphate along with a present of 300,000 maravadís and a promise not to give aid to his rebellious nobles. Instead, Alfonso took the money and not only continued fomenting insurrection with the Banu Ashqilula in al-Andaluz, but started encouraging the Abdalwadid ruler, Yaghmorassan of Tlemcen to rise up against Abu Yusef in the Mashriq.

Whilst Alfonso's meddling was coming to a head, Richard of Cornwall died, and the king dropped everything to pursue the crown of Christendom once again. This time, he intended to travel to Italy make his case to the pope in person, but the pope thwarted his ambitions and met him in Provence. After a long, stern bout of negotiations, he obtained Alfonso's word that he would abandon all attempts to claim the title of King of the Romans. It was during these negotiations, whilst his oldest son, crown prince Ferdinand de la Cerda was acting as prince regent of Castile, that the future of Iberian Christendom faced the greatest threat since the initial Islamic invasion.

Realising by now that he had been lied to, the Nasrid ruler, Muhammad II of Granada, appealed to the Marinid emir Abu Yusuf Yaqub for assistance, but the Marinid emir was already engaged against Tlemcen and couldn’t help. The civil war in his caliphate worsened, and Muhammad renewed his request to the Marinids for assistance, offering them the Iberian towns of Tarifa, Algeciras and Ronda as payment. This very tempting offer arrived just as Abu Yusef crushed the uprising in Tlemcen.

With his enemies now subdued, Abu Yusuf Yaqub took up the Nasrid request, and in April 1275, crossed the straits to land a 50,000 strong Moroccan army in Spain. The Marinids quickly took control of Tarifa and Algeciras, and confirmed their pact with Muhammad II. The Banu Ashqilula were now hugely outnumbered and promptly capitulated, and the Emir of Granada immediately ordered the commanders of his 80,000 troops to invade Castile and take back Córdoba. Alfonso´s son was now facing invasion by a vastly superior force on a 300 mile front, and was totally unprepared for war.

Abu Yusef and his son drove their army north, destroying everything in their path and enslaving the newly-settled Christian farmers. When Prince Ferdinand received news of the invasion he called the nobles of all the kingdoms to arms and managed to raise enough men in time to meet the invading Marinids in the west, whilst his younger brother, Sancho, led another army against the Nasrid forces around Córdoba. But on the march south, before battle could be met, Prince Ferdinand fell sick and died near Villa Real.

Nuño González de Lara "el Bueno", the head of the House of Lara, took control of the army and attempted to halt the Marinid advance in a battle near the town of Écija in September. The Christians were routed, and Nuño was captured or killed. Abu ordered his head cut off and sent to Muhammad as a trophy. The Christians, after regrouping and being reinforced, mounted another attack a month later led by Archbishop Sancho of Toledo, which met a similar defeat at the Battle of Martos. The Archbishop was killed, and it was only the efforts of King Alfonso’s son, Sancho, who rode from the defence Córdoba to take the lead at the head of his father’s army in the west that saved the day.

By now, King Alfonso had returned from France, and he immediately sent a plea to Abu to end the war and open negotiations for peace. His primary mission achieved with the aid to the Nasrid caliphate, and thousands of slaves and cattle as a prize, Abu agreed.

King Alfonso had made some mistakes with his rule, but his biggest mistake was yet to come, and it would tear his kingdom apart. But out of it would come two of Spain’s greatest heroes, and one of its greatest villains.