In early May 1492, Columbus, a newly appointed admiral in the Royal Spanish Navy, showed up at the port of Palos under orders to conduct an expedition westward looking for a route to the Indies. He had with him letters of introduction signed by Queen Isabel of Castile which instructed the port authorities to impress a squadron of three caravels with supplies and crews who thereafter would serve in the navy at regular seaman’s pay. Two of the caravels were to be selected by the port authorities, but the flagship and its captain were to be selected by Columbus.

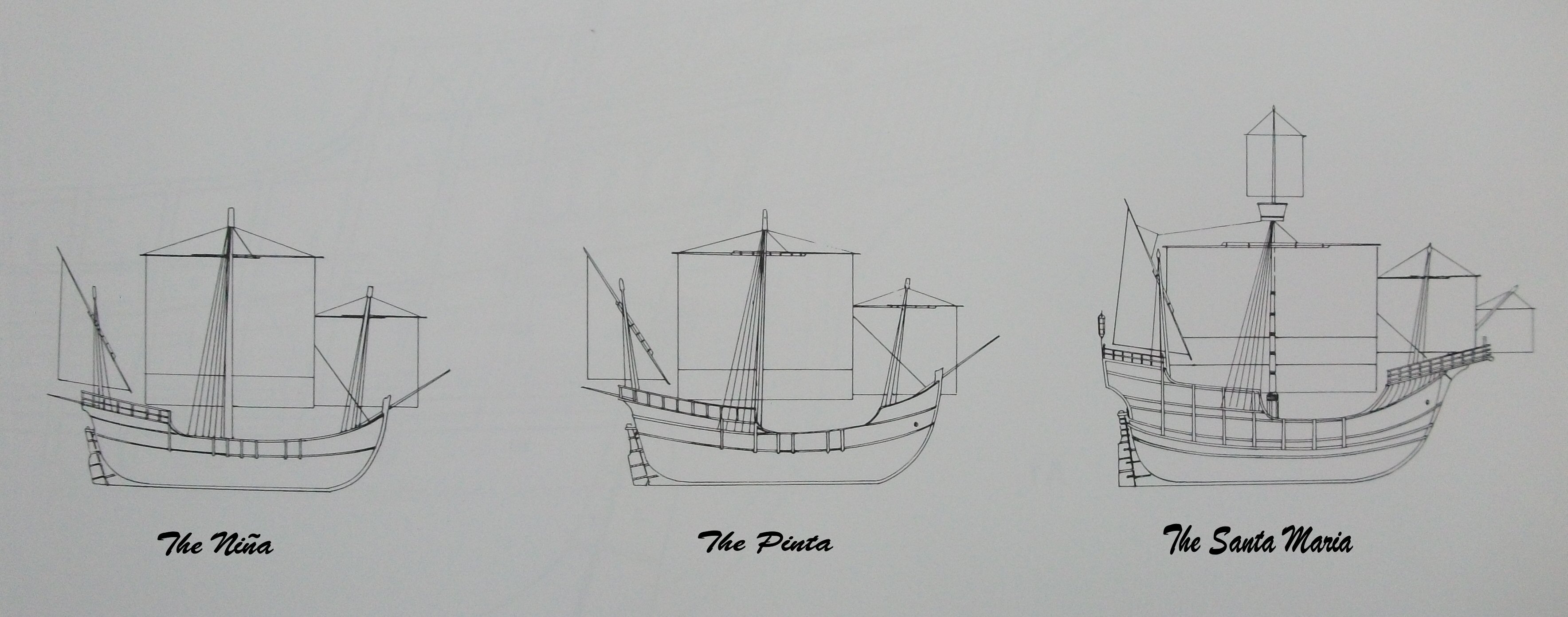

The sailors of Palos knew about Columbus’ insane mission and wanted none of it. The orders given to Columbus by Queen Isabel stated that he should be given “every assistance” to organise his ships and crews. Isabel even set a time limit upon how long it should take. She allowed the authorities ten days to comply. Ten weeks after he arrived, Columbus was still not ready to sail. He did not have time or money to browse the nearby ports to select ships, and was obliged to accept whatever they gave him. Eventually, the port authorities impressed the Niña and the Pinta, quite small caravels with a single deck each.

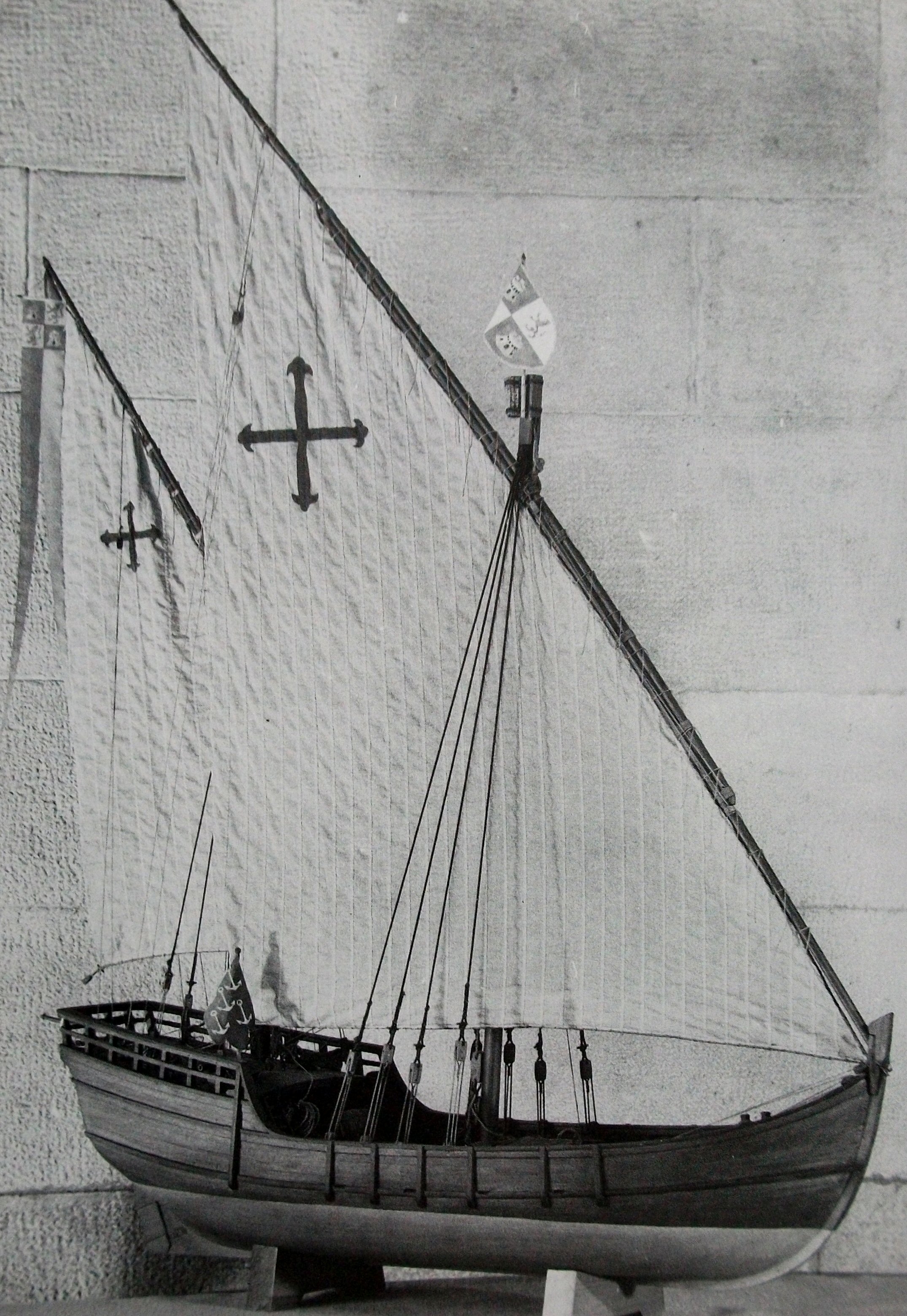

Photo Niña: Museo Maritim, Barcelona. Shown here before her lateen rigged sails were changed to square rig.

It was customary in those days to name your ship after a saint, and the Niña was actually called the Santa Clara; Niña was a pun on the name of the owner, Juan Niño de Moguer. On Columbus' first expedition, the Niña carried a crew of 26 and was captained by Vicente Yáñez Pinzón.

Photo: Pinta, Museo Maritim, Barcelona.

Martín Alonso Pinzón, brother of Vicente, captained the Pinta, and both were respected and well known captains from Moguer in Andalucia. Columbus now had to choose a flagship for his little fleet and find a captain willing to command it. This simple task would not be easy. The crews of all the ships were officially volunteers, but none of them wanted to sail on this voyage, and they showed it with non-cooperation and complaints before they had even left port. Their problem was that Columbus reported to the queen, and in effect had absolute power over all.

Exploration in the late 15th century was in the hands of a small class of veteran mariners who knew each other and shared information on navigation and were constantly updating their charts. Mariners who found new islands or ports made their own hand-drawn charts called portolan charts. Whenever a mariner returned from a voyage, he checked in at the office of the chief navigator, who would be a captain or other officer, to add his portolan charts and see what was new on the Mappa Mundi, the world chart that was constantly being updated by professional cartographers. One such office was in Puerto Santa Maria near Cádiz, and it was overseen by Juan de la Cosa.

It was while Columbus was looking around for a ship and a captain for his perilous voyage that he met Juan de la Cosa, who was visiting Palos at the time. Juan had his own ship, a nao called the Santa Maria, which was not exactly what Columbus was looking for, being slower and broader on the beam than the other two ships, but it came with a captain with impeccable credentials. The origins of Juan de la Cosa are obscure and confusing. It seems that he was originally from Galicia, and the high proportion of Galicians in the crew of the Santa Maria would support this, but in later correspondence with the crown over payment for his crew and the loss of the Santa Maria, he is recorded as a vecino of Santa Maria del Puerto, which is not the same El Puerto Santa Maria across the bay from Cádiz.

Photo Santa Maria. This is the 1927 replica near Huelva as reconstructed by Guillén. Photo: The Manuel Ripoll collection.

Columbus wasted no time in recruiting Juan and his ship. His expertise as a captain was beyond question, but it was his navigation and map-making skills that set him apart from other captains. If new lands were discovered he would need Juan’s skills to record them as evidence to present to the queen. As an admiral, Columbus would not actually do any sailing. The protocol, which went back to Roman times, was that the admiral commanded the fleet, but individual captains were in command of their own ships. The relationship between Columbus and Juan de la Cosa became strained from the start because Columbus constantly interfered with Cosa’s orders, and this would lead to problems later on. Finally, with his ships loaded, Columbus left Palos de la Frontera on 2 August 1492 and sailed down the Rio Odiel on the ebb tide to the Saltes sandbar. They anchored there for the night, and at 8 o’clock the following morning, with a favourable tide behind them, they set course for the Canary Islands.

The passage to the Canaries took six days, and by before they reached the coast of Africa the Pinta required jury-rigged repairs to her rudder. In his voyage notes, Columbus wrote that he suspected sabotage by its owners, Gomes Rascon and Cristo hal Quintero, who were unhappy that their boat had been requisitioned against their wishes. These two had already been stirring up trouble in Palos before the fleet had left. However, the admiral had every confidence in the Pinta’s captain Martin Alonso Pinzón whom he spoke of as “a brave and intelligent person.” Nevertheless, as the short voyage progressed, the hull of the Pinta began to leak and Columbus had serious doubts as to whether the boat was capable of an Atlantic crossing.

It became clear that they would have to stop at the Canaries and either make lasting repairs or hire another boat. They sailed to Gran Canaria and the port of Las Palmas, where the Pinta left the other two ships and docked at the small port of Gando which had facilities to repair the Pinta’s rudder. Meanwhile, the Santa Maria and Niña continued on to Gomera where Columbus ordered the conversion of the Niña’s lateen rigged sails to square sails which would be better for open-ocean travel. Both ships then returned to Gran Canaria to join the Pinta, whose rudder had now been repaired and her hull caulked.

Drawings courtesy of Xavier Pastor from his book The Ships of Christopher Columbus.

The united fleet sailed the 90 miles to Gomera, where they docked and took aboard final provisions for the voyage. It was whilst he was in the harbour at Gomera that a caravel arrived from Hierro bringing the news that three Portuguese caravels were patrolling the islands looking for Columbus' fleet. Because he had heard that Isabel had funded his voyage, the jealous and avaricious King of Portugal had ordered their capture, no doubt to offer Columbus a different contract of employment, or incarceration.. With no time to waste, before sunrise on the morning of 6 September, all the crews heard Mass together, and as the sun was rising, they left Gomera going west. To add to Columbus’ disquiet, the wind immediately dropped, and the fleet was becalmed in sight of Gomera and began drifting towards Tenerife on the current. It must have been an unnerving afternoon, because Mt. Teide had been erupting pretty much constantly during their stay, and there was nothing that they could do to halt their drift towards the volcano. At three in the morning of the 8th, the wind freshened from the northeast and brought with it a heavy sea, and the little fleet finally began to make slow headway to the west.

The first and subsequent voyages of Columbus are considered as, to quote a much later adventurer, “a giant leap for mankind.” There have been several events to celebrate the voyage. The first was in 1892 on the 400th anniversary of the first crossing.

A full-size replica of the Santa Maria was built by La Carraca shipyards in Cádiz under the direction of a Commission presided over by Captain Cesáreo Fernández-Duro. There were no plans of the original Santa Maria, and the builders only had Columbus’ notes to work from, but the Santa Maria was a nao, which was a very common type of vessel in use at the time.

The plan was to sail her to the World Trade Fair at Chicago, and when finished, she was towed to Palos de Moguer and symbolically left port on 3 August (The same date that Columbus sailed on.) escorted by two lines of warships from different nations. Unfortunately, it was found that there were errors in her design that would make an Atlantic crossing dangerous, and she was towed back to Cadiz for alterations. Finally, on 10 February 1893, she set sail for the Canaries, where she stopped at several ports before leaving Santa Cruz de Tenerife on the 22nd bound for America. She reached San Juan de Puerto Rico on the 30 March after thirty-six days of sailing. (One day less than Columbus took.) From there she sailed to New York, Quebec, Montreal, Charlotte and Toronto, finally reaching Chicago on 17 July 1893.

It was 1927 before another attempt was made to construct a replica of the Santa Maria. During the intervening years since the first one had been constructed, Julio Guillén, a Lieutenant in the Spanish Navy, had published a book named La Carabela Santa Maria. He had researched the old records and proposed that the Santa Maria had been a carabela de armada and not a nao. The 1892 replica had been a hybrid of the two different types of vessel and whilst each type had proven to be seaworthy, mixing the two types of design had caused problems. The construction of a new replica was begun in the Echevarrieta shipyard in Cádiz. The new Santa Maria was exhibited at the Exposicion Iberoamericana de Seville in 1927 and was later anchored off the monastery of la Rabida in Huelva. Sadly, in 1945 she was being towed from Valencia to Cartagena for repairs when she sank. Guillén was later to become Director of the Naval Museum in Madrid and a member of the Academia de la Historia, during which time he wrote several books on naval history.

The most bizarre episode concerning Columbus’ voyage began when José Martinez Hidalgo y Terán, a Commander in the Spanish Navy, and Director of the Museo Maritim de Barcelona for 20 years, asserted that the Santa Maria was a nao, and his meticulous research led to the construction of another replica to be exhibited at the New York World Fair of 1964/5. She was built by the Astilleros Cardona, and when completed, was loaded onto the German freighter Niedenfield in Barcelona. The Niedenfield took her to Mench’s Boulevard, Flushing, where the 80 ton ship was loaded onto a road transporter and driven the three miles to the exhibition site. This involved the transporter with its 90 ft. long load passing through the Queens District of New York. Escorted by a flotilla of police cars and with technicians taking down telephone wires and cutting back trees along the route, the Santa Maria was finally lowered into Meadow Lake, where she was moored for the exhibition.

Lastly, in 1992 construction began of replicas of all three ships which then sailed together along the route that Columbus took. They are now displayed in the Muelle de las Carabelas (Wharf of the Caravels) in Huelva. (Another place that I am going to visit post Covid.)