Even though he had made huge navigational mistakes and entirely missed the significance of Viking legends, Columbus did get one thing right. Traders who had plied sea routes in the open Atlantic were aware of the wind patterns of that ocean. From the Canaries, the prevailing winds are easterlies. These winds would quickly take the Columbus fleet far out into the Atlantic. But the terrifying thought for crews on Columbus’ little boats was that on the return voyage the wind would be against them.

The only way for his ships to sail against a prevailing wind was by tacking, which involved arduous zig-zagging and changing the set of the sails at the end of every leg. Modern yachts are fore-and-aft rigged, and can sail to within 45 degrees of a headwind, but square rigged sailing boats could only achieve a fraction of this. The boats that he had were all square rigged. He had changed the Lateen rigged sails of the Niña to square rigged because he had a good idea that he would not need to tack so much, and square rigged boats would make better speed with a following wind. Columbus’ secret weapon was that he knew that if he navigated to the North Atlantic, where the prevailing winds were from the west, they would carry him home to Northern Spain. Only a decade later, when crossing the Atlantic became commonplace, these circulatory winds would be known as the trade winds. But when Columbus sailed they were relatively unknown.

Columbus’ fleet made good progress, and after four weeks of sailing were beginning to enter truly unknown waters now, and the worst fear for any mariner is to come upon shallow water or a rocky shore in the night or in a storm. Some of the crew were beginning to question the wisdom of letting the prevailing wind drive them into hazardous waters. Mutiny, never far from the crew’s minds, was beginning to show itself.

Columbus had kept two charts from the beginning of the voyage; one to show the crew, and one showing their real position. After each day’s progress he noted the distance covered in the real log but wrote a lesser distance in the log for the crew to see. He did not want them to see how far from home they really were. Columbus made a display of taking readings with his quadrant and was happy to reassure the crew by explaining his navigation. He of course had a magnetic compass, although during the voyage, Columbus noted a magnetic deviation of 11.25 degrees west; the first time that this phenomena had been seen. Sighting the Pole Star through the quadrant would give his latitude above the equator. This was important. He did not want to stray too far south and miss China, which was at the same latitude as his starting point of the Canary Islands. He could stray north, which would bring him to Japan at the same latitude as mainland Spain. Staying between these two parallels was essential.

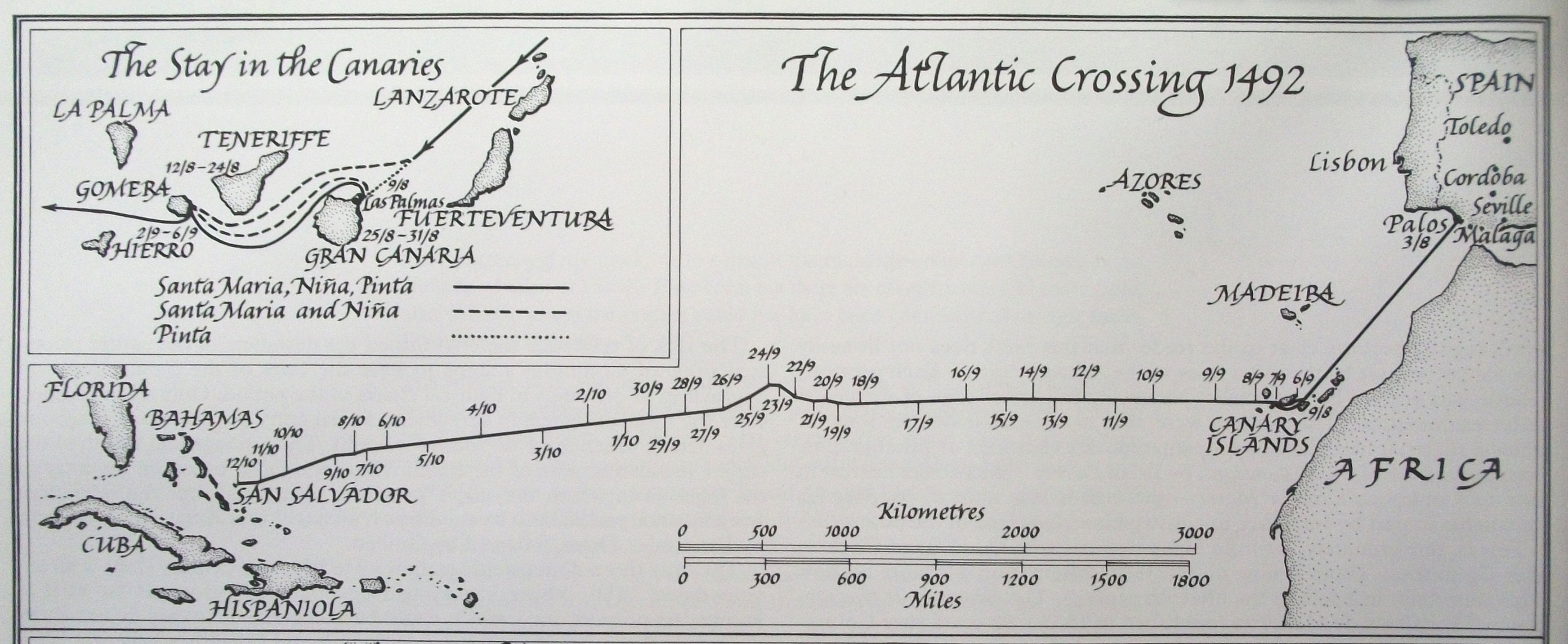

Map of Columbus' course taken from his logs. Map from The Ships of Christopher Columbus by Xavier Pastor.

He had kept a log of speed by dropping a wooden float on a rope which had knots tied in it at measured distances. By counting the knots reeled out as the float passed a mark on the ship’s stern they knew their approximate speed. Last of all, the job of the cabin boy was to turn the hourglass in the Captain’s cabin and note the hours in the log. With these four pieces of information Columbus could navigate by what is now called “dead reckoning,” and he was first among sailors of the time to keep a complete record of all his calculations. It’s from these logs we can chart his progress today. On this first voyage westbound, Columbus stuck to his (magnetic) westward course for weeks at a time, and only departed from it three times; once because of contrary winds, and twice to chase false signs of land southwest.

Celestial navigation was just being developed by the Portuguese, and Columbus tried his hand at tracking his position using sightings of the stars. On his first voyage he made at least five separate attempts to measure his latitude using celestial methods. Not one of these attempts was successful, sometimes because of bad luck, and sometimes because of Columbus’ own ignorance of celestial navigation.

By the first of October, Columbus records that his “pilot”, who could only be Juan de la Cosa, had begun to question his records of the distance covered. After a rainstorm that lasted most of the day Columbus was challenged about his log entries. Remember that Juan was an accomplished cartographer and navigator, and was watching everything that Columbus did. Juan claimed that the fleet had covered more distance than the admiral was recording. He was right; Columbus made a show of displaying his charts showing that the fleet had covered 584 (2016 miles.) leagues since leaving the Canaries, but his own secret log records 707 leagues (2440 miles).

Nevertheless, the crews on all three ships were unhappy, afraid, and ready to mutiny. The mood lightened considerably when after 29 days out of sight of land, on October 7, 1492, the sailors spotted “immense flocks of birds" and Columbus changed course to follow their flight. Several of the birds were trapped by the crew who determined that they were land birds. (Probably American golden plovers) The following day brought more unrest from the crews and the admiral was forced to placate them with promises of fabulous wealth to come. On 11 October, Columbus changed the fleet’s course to due west, and pressed on through the night, believing land was soon to be found.

Queen Isabel had promised the prize of an annuity of 10,000 maravedís to whoever should be first to see land, and La Pinta, being the fastest boat of the three, forged ahead hoping to collect the reward. At two in the morning, a sailor named Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodríguez Bermejo) yelled that he had sighted land. La Pinta’s captain, Martín Alonso Pinzón, verified the land sighting and alerted Columbus by firing a lombard. (A small cannon.)

Meanwhile, on the Santa Maria, Columbus’ log shows that four hours earlier, at 10pm the previous evening, the Admiral had seen a light "like a little wax candle rising and falling" and called Pedro Gutierrez Groom, who had served in the court of King Ferdinand, to confirm the sighting. He also asked Rodrigo Sanchez de Segovia, whom the King and Queen sent with the fleet as Inspector, to verify what they had seen. Their opinions differed, so Columbus called the crew together to say the Salve and ordered a special watch to look for land from stern forecastle. When the call came from La Pinta a few hours later, Columbus ordered the furling of sails and the fleet stood off until daylight.

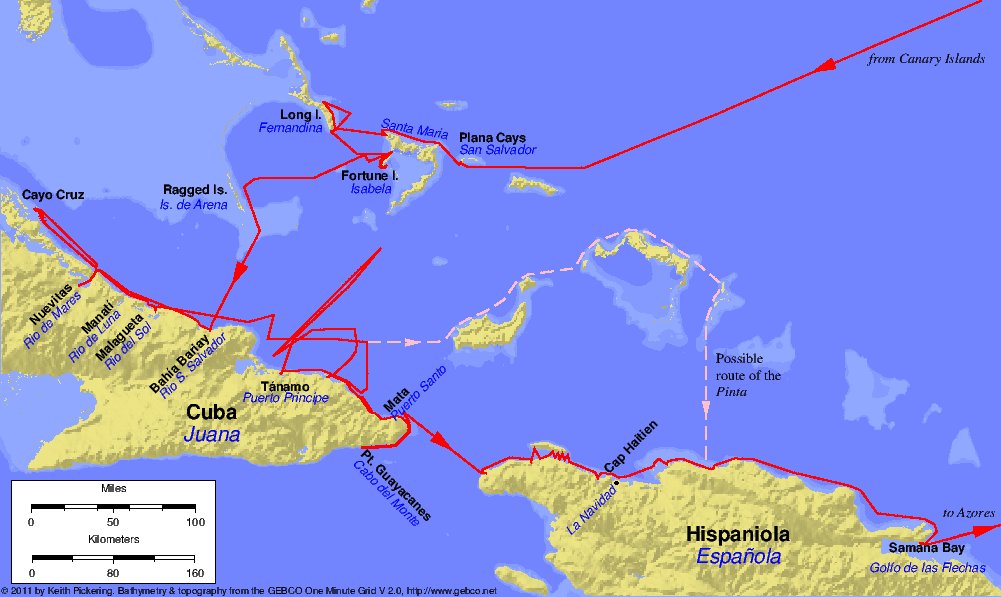

Landfall map by Keith Pickering.

(Modern sailors have tested Columbus’ claim by taking a boat to the position where he noted that he saw the light, whilst others lit a fire on the highest point of Plana Cays, the modern name of the island. True enough, the fire could be seen in the night, but it still does not prove that Columbus did not fiddle the log. However, you have to remember that Columbus’ son had possession of his father’s logs long after his death, and he may have removed or added parts. For instance, there is hardly any mention of Juan de la Cosa, the man closest to Columbus during the voyage, and the rightful captain of the Santa Maria. It is only after the voyage the captain’s true significance was revealed.

On the morning of Friday October 12, the three ships cautiously approached the shore. The lookouts saw natives on the beach and in the forest along the shore, and Columbus ordered that the men who could use them be issued with swords and firearms.

Columbus had a speech prepared for the respected witnesses supplied by the Queen and King of Hispania who were on hand to record the event. The captains of the Pinta and Niña, Alonso Pinzon and Vincente Yafiez boarded the dory carrying the royal banner, a green cross on white background with the letters F and Y surmounted by the crown of each kingdom in the upper quarters of the standard. They were accompanied by Rodrigo Descoredo, Notary of all the Fleet, and Rodrigo Sanchez of Segovia with a handful of armed soldiers.

A woodcut of the landing by Theodor de Brey.

Once upon the sand, Columbus fell to his knees and thanked God for a safe arrival and a successful voyage. When he had regained his composure, he called the witnesses to him and gave his carefully prepared speech in which he claimed to all that he was taking possession of these islands in the name of the king and queen. The witnesses solemnly gave their testimony and duly recorded it in their own personal diaries to show the king and queen upon their return to Spain. All the years of planning and doubt had vanished when he stood upon the sand of that island. He had earned his title of Admiral of the Oceans, but in reality his troubles were just beginning. Not least of which were the dozens of naked savages who had silently walked from the surrounding jungle and now surrounded them.