While Columbus was planting the symbolic flag of Castile and Aragon in the sand and giving his speech, the natives had come out of the forest and onto the beach to see what these strange men were doing. Totally naked, but wearing rings, bracelets, anklets and necklaces they surrounded the solemn group of Spaniards. Columbus’ crews watched them warily, but were not concerned; none of the natives were armed, and they were. However, the crew and visiting dignitaries noted that some of the baubles that the natives were wearing were made from gold. With the formalities over, Columbus ordered the distribution of brightly coloured caps and beads to the natives, which in his own words were “Of slight value, but in which they took great pleasure.”

One of two flags used by Colunbus to claim the islands for Isabel and Ferdinand.

One of two flags used by Colunbus to claim the islands for Isabel and Ferdinand.

Columbus described the natives in his log. “They were very well built with very handsome bodies, and very good faces. Their hair was almost as coarse as horses' tails and short, and they wear it over the eyebrows, except a small quantity behind, which they wear long and never cut. Some paint themselves blackish, and they are of the colour of the inhabitants of the Canaries, neither black nor white, and some paint themselves white, some red, some whatever colour they find: and some paint their faces, some all the body, some only the eyes, and some only the nose. They do not carry arms nor know what they are, because I showed them swords and they took them by the edge and ignorantly cut themselves. They have no iron: their spears are sticks without iron, and some of them have a fish's tooth at the end and others have other things.”

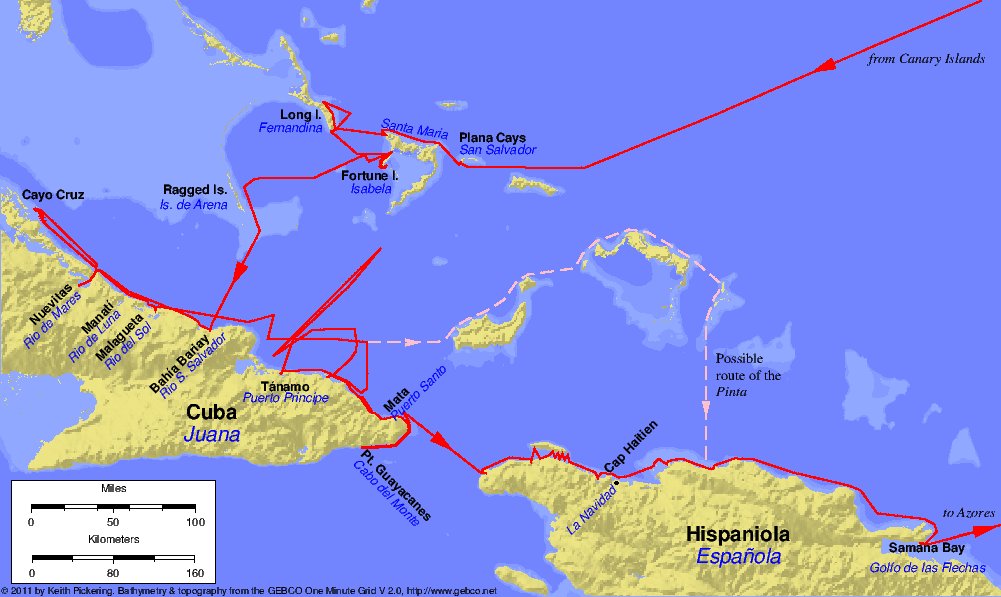

Using sign language and a few learned words, Columbus ascertained that the natives called the island Guanahan, which was probably one of the Plana Cays islands in the Bahamas. He was still of the opinion that he had landed on islands to the east of Cipango, (Portuguese for Japan) and he noted this in his log. Convinced that he must continue sailing westwards to find China, (The log showed later amendments replacing Japan with Cathay, or China.) he began questioning the natives about nearby islands. He especially wanted to know the source of the gold in their jewellery. With a number of native guides on board he took his small fleet further westwards and called at other islands giving each of them names in honour of Spain. (Santa Maria de la Concepción, Fernandina, and Isabela.) The three ships finally landed at Bariay Bay, Cuba on October 28. Columbus named the island Juana and began exploring the coastline.

Each time the three ships passed a settlement, the natives paddled their canoes out to greet the newcomers to invite them to see their villages. Columbus wrote that they were friendly and helpful and lived in a pyramidal tribal structure with village chiefs who acted as arbiter for disputes. By 5th November Columbus’ men had collected samples of spices which would fetch a good price in European markets. Columbus was pleased with the spices, but he had had never forgotten that it was his promise of gold that had persuaded Isabel and Ferdinand to support him, and he questioned the natives relentlessly about the source of their gold jewellery. He was told that the gold came from a nearby island called Babeque.

On the 6th, they were invited to a feast in a mountain village of 50 houses, which Columbus estimated had a population of 1000. As the Spaniards learned more of the language, they realised that the natives thought the Spanish were from heaven. They were shown around the village and invited into the houses, where they noted that the wooden furniture was often elaborately carved in the shape of animals, but with eyes and ears fashioned in gold.

It was here that the Spanish were invited to smoke tobacco for the first time, and they packed a sample the aromatic leaves in with the large amount of spices they had collected. They knew that the spices were expensive in Spain, and would be of interest to the traders. The tobacco leaves were an afterthought because they had no obvious value. (Of course, tobacco spread throughout Europe and Asia and gave pleasure to millions, but in hindsight, probably brought early death to millions.)

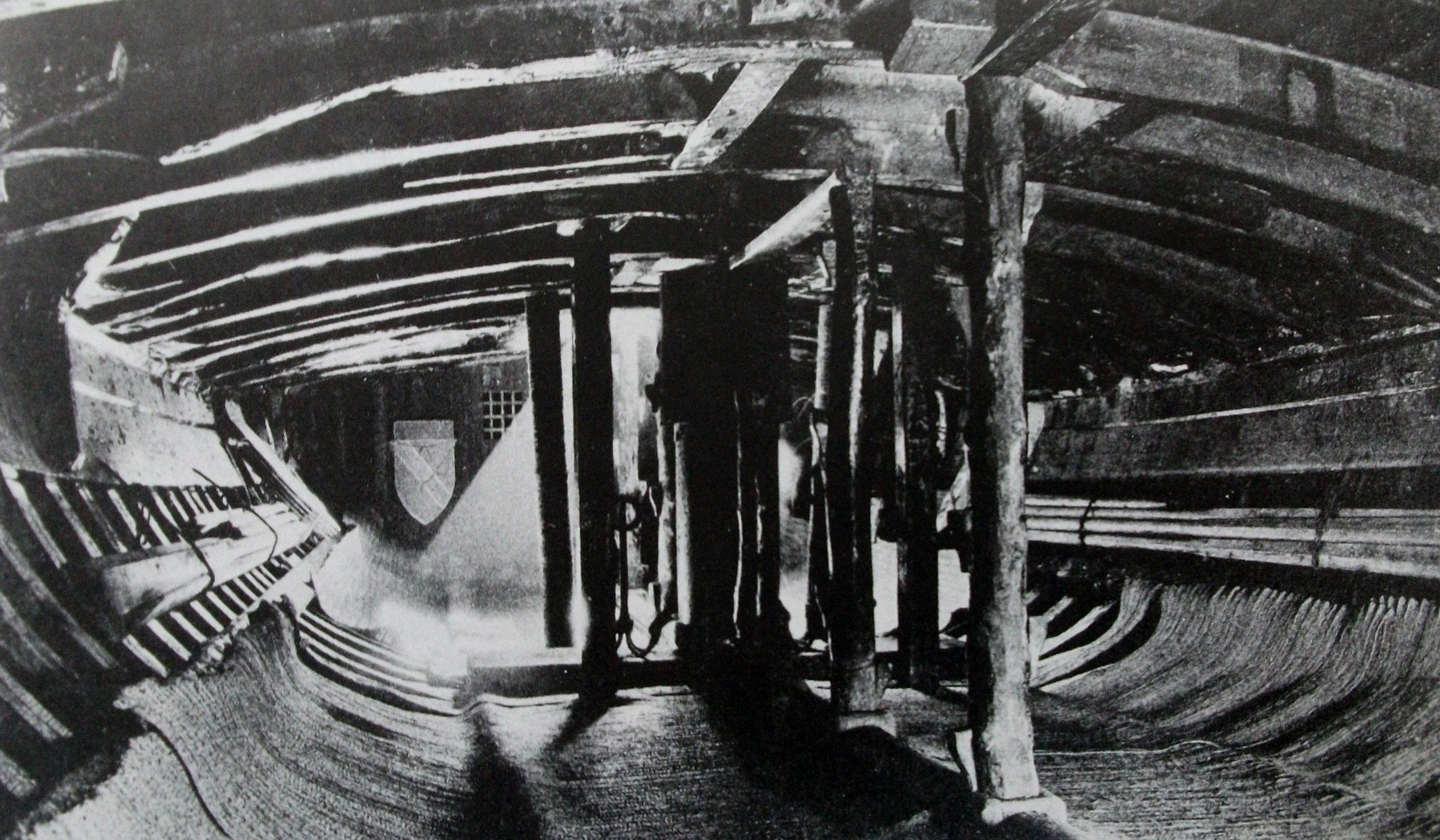

The Hold of the Santa Maria. Museo Maritim Barcelona.

What immediately caught the attention of the sailors were the hammocks that the natives slept in. For the natives, the hammocks were essential because they raised the sleeper off the ground where insects and poisonous snakes were a constant danger. For the sailors who slept in tiered bunks they were a revelation. To be rolled out of the top bunk in heavy weather often meant broken bones, but here was a bed that swung with the movement of the ship and left the occupant undisturbed. Even during relatively calm weather, anybody who has tried to sleep in a wooden bunk on a ship that rolls and pitches will testify that it is misery. Trading was brisk in hammocks, and when the three ships returned to Spain, many of the crew would spend their rest-time sleeping soundly in their hammocks. This astoundingly simple idea spread throughout every navy, and was probably the only thing from Columbus’ voyage that would benefit sailors everywhere who were about to face much longer voyages of trade and exploration.

Above: The gun deck of the Santa Maria where many of the sialors would have slept. Museo Maritim Barcelona.

By 1590, hammocks had been almost universally adopted for use in sailing ships; the Royal Navy formally adopted the sling hammock in 1597 when it ordered three hundred bolts of canvas for "hanging cabbons or beddes”. Aboard ship, hammocks were regularly employed for sailors sleeping on the gun decks of warships, where limited space prevented the installation of permanent bunks.

Columbus gave orders to encourage some of the natives to come on board his ships with the intention of using them as guides to help navigate amongst the islands, but with a longer term plan to take some of them back to Spain to show the king and queen. With natives on each ship, the little fleet sailed north-east along the coast of Cuba. Columbus was still convinced that he was off the Chinese mainland and was determined to present himself to the Great Kahn in Cathay. The wind was against the fleet and they made little headway before returning to a river that the admiral had called Rio de Mares. By now many of the natives were becoming wary of the Spaniards’ motives in keeping them aboard their ships. He sent parties ashore, but the natives of the villages had abandoned their villages and fled, and he ordered his men not to take anything and leave the villages untouched.

Finally, a canoe with six youths approached the Santa Maria and five of them came aboard. Columbus immediately ordered them to be restrained. He sent men out to search for natives, and they returned with seven captured women and three children. Later on that evening, the father of the children and husband of one of the women came to ask to be reunited with his family and Columbus kept them all together. In his log he writes that he was pleased that the natives had decided to stay and that he would present them to the king and queen, but it had become clear to the natives that they were prisoners not guests. Finally, Columbus decided that he had enough spices to tempt the European traders, and gave orders to prepare for the voyage to Babeque to find the source of the gold.

The captain of the Pinta, Martin Alonso Pinzón, had fallen out with Columbus on several occasions before and during the voyage, and now he had natives aboard who told him that they could take him to the island of Babeque and show him where the gold was mined. They must have told Pinzón much more than they told Columbus, because Pinzón secretly hatched his plan to go gold hunting alone.

On 21 November, as the fleet prepared to sail to Babeque, Pinzón had a blazing row with Columbus, and when the ships left the coast of Cuba, the Pinta, being the fastest ship in the fleet, pulled away into the lead. The log shows that the ships made several course changes in open water before the Santa Maria and Niña returned to the coast of Cuba whilst the Pinta went off alone. Columbus was furious, but adverse winds kept the remainder of his fleet at anchor off the coast of Cuba. The lure of fame and fortune was beginning to erode the discipline of the small fleet, and it was only going to get worse as the voyage continued.

Log extracts show the confused courses plotted just before the Pinta left the other two ships. Map: Keith Pickering.

After Martin Alonzo Pinzón pressed on with his own search for gold in the Pinta and leave the other ships behind, Columbus changed course to the south-east. The Santa Maria and Niña held this course through the night, but in the morning they discovered that they had made little progress. The wind and adverse currents had been against them. Columbus rightly guessed that Pinzón in the Pinta had also made little progress, so he ordered that the next night he would show a light so that Pinzón could return. Whether Pinzón never saw the beacon or chose to ignore it is not known, but the next morning with the wind against him, and with no sign of the Pinta, Columbus ordered his ships to turn back to the coast. When they landed, the Indians fled and would make no contact. His men found cultivated fields and a canoe made from a single tree that was easily capable of crossing between the islands, but not a single native was to be found.

With the wind against them, the two ships dropped anchor and sheltered in the mouth of a river. Everybody was impressed with the variety of trees and grasses, many of which they recognised as the same as in Spain, but on every foray inland, the natives eluded them. The natives that he had on board as guides were pleading to be allowed to be returned to their homes and families and they warned Columbus that the natives on this new coast were dangerous, and that he should not try to deal with them. But Columbus had not come this far to be deterred by unarmed savages. From what he had seen so far, they were the most docile and friendly of people, once you gained their trust. He had yet to see the natives carrying any kind of weapon that would be a threat to musket, sword and cannon.