With the Pinta gone gold hunting alone, Columbus had to spend a frustrating two days at anchor whilst the wind was against them. The wind finally came round to a more favourable direction, and after sailing down the coast of Cuba, Columbus crossed the Windward Passage to the island now known as of Hispaniola. For the Santa Maria the passage was slow, but Vicente Yáñez Pinzón on the Niña was making good speed and went ahead to look for a safe harbour before night fell. Vicente showed a light so that Columbus could follow, but the admiral was unsure and decided to wait until daylight before he entered the harbour.

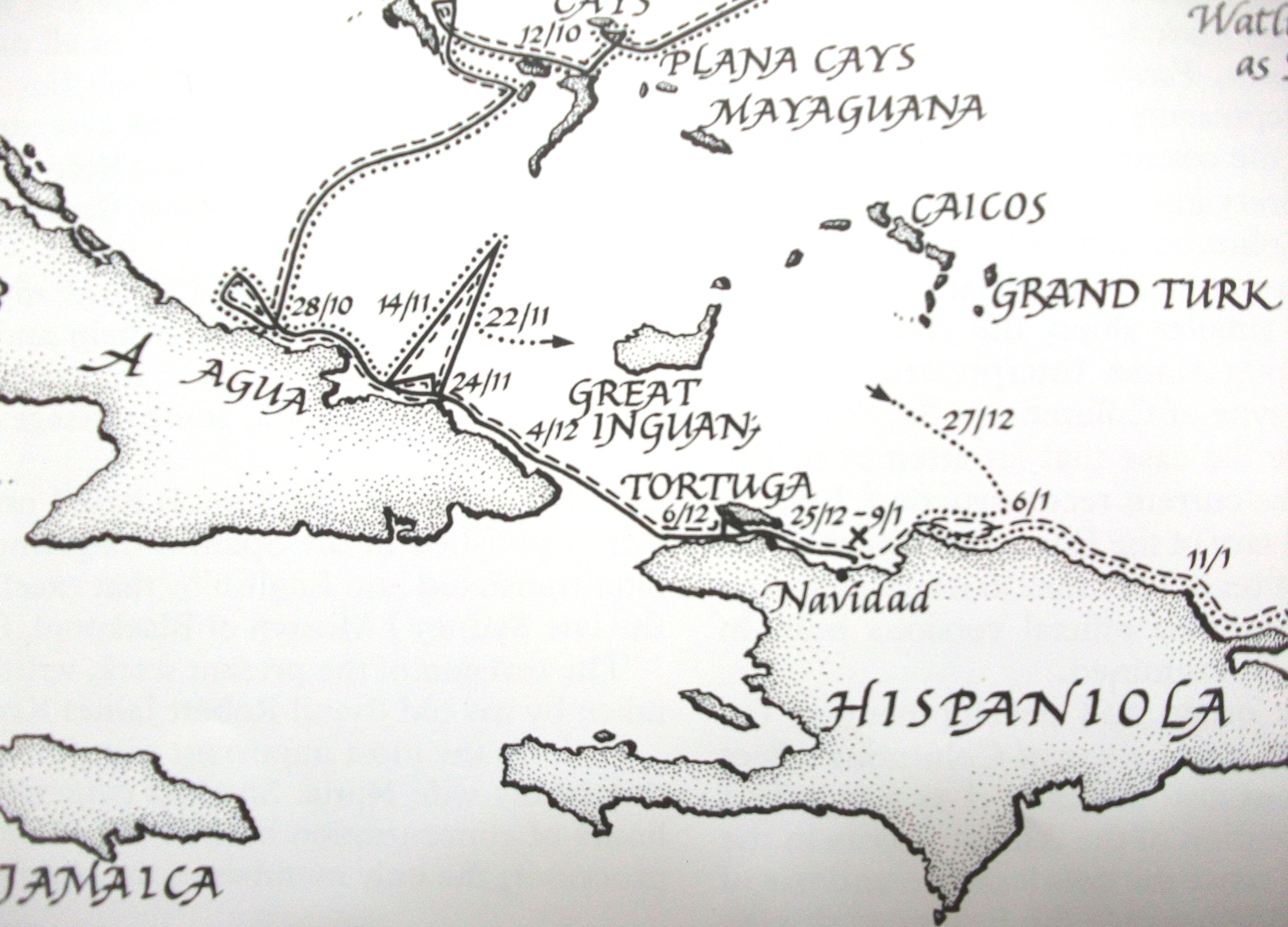

Map; XavierPastor

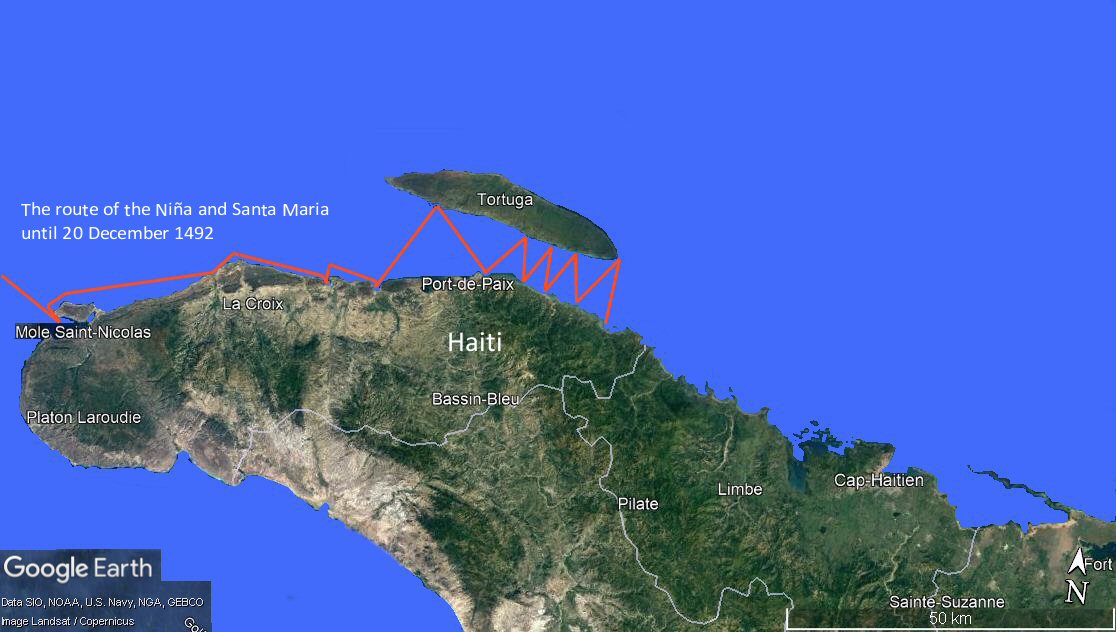

Map; XavierPastor

On 6 December the Santa Maria anchored in what turned out to be an excellent natural harbour which he named Puerto Maria. There were several smaller neighbouring islands, and that night on an island to the east, which he had named Tortuga, he saw campfires and the next day columns of smoke. The natives with him said that they called this larger island Bohio. There were no signs of natives here and so he decided to sail further along the coast, and over the next couple of days the crews on both ships caught some of the abundant fish to supplement their meagre rations.

He called the new island Española, and though the natives had fled, there was plenty of evidence of their existence. During the night they had seen fires and the sharp eyed among the crew had seen what looked like watch towers on high points of the island. The natives were still elusive, but the crews caught glimpses of them as they abandoned their canoes on the beach and fled into the forests.

During the 10th and 11th the skies were grey and the wind blew from the north-east, causing the small ships to drag their anchors. With no more exploring by sea possible, Columbus ordered six well-armed men to go ashore and see if they could make contact with the natives. They returned with descriptions of wide tracks, but just a few wooden huts. The natives on his ships were becoming more insistent that they wanted to be returned home and set free. They told Columbus that these islands were inhabited by cannibals because when they captured people they were never seen again. Columbus took this to mean that a superior powerful empire had been conducting slaving raids on these peaceful, hapless people. This empire could only be the Great Khan of China.

His mind was now focused on finding the source of the gold that he had seen the natives use for trinkets. Gold had been his promise to Isabel and Ferdinand, and no amount of spices would make up for the lack of it.

The wind was still holding them at anchor on the 12th and Columbus once again ordered armed men ashore to try to find indigenous natives, but this time he sent some of his captured natives with them. His men planted a wooden cross on the rocky shore and struck off inland. Before long they found a village, but the natives fled and only one young, beautiful, girl was left behind. Columbus’ natives talked to her and brought her back to the ship where she was given clothes and food and sat with the other native women, who convinced her that the Spaniards were not bad people. Columbus allowed her to return to the shore and sent three men with her. They returned after midnight saying that they had travelled several leagues inland and were afraid to accompany her any further. The next morning he sent nine more armed men and a native to follow the route taken by the girl.

The found a wide valley which had been cultivated and a village of possibly three thousand people, but totally deserted. After calling to them their native managed to persuade some to come out of hiding. After more calming words, and seeing that the Spanish were not hostile, the natives flooded back to the village. Columbus writes that many of the natives were shaking with fear as they returned to their houses. Once it was clear that the Spaniards meant no harm they showered them with presents. Despite all the shows of friendliness, the Spaniards saw no gold ornaments or jewellery.

The two ships crossed to the island of Tortuga, but the contrary wind kept them from landing. They saw houses, but the natives there, too, had fled, and so they returned to Española. Over the next few days they made several trips to Tortuga with little success and were forced to return to Española where they had made friendly contact with the natives. On the 16th they came across a native alone in a canoe crossing the straits in heavy weather and took him and his canoe aboard. They landed him on Española close to a village and allowed him to paddle ashore.

Picture; Alan Pearson. alanpearson.pixels.com

Within hours around 500 natives had filled the beach, and they paddled out to the anchored ships in their canoes. They brought no gifts, but the Spanish crewmen noted that they had gold piercings in their ears and noses. Columbus ordered that the natives were to be treated honourably and not exploited for their gold jewellery. Shortly afterwards, their king appeared on the beach, a young man of about twenty years, who was surrounded by councillors and advisors. One of Columbus’ natives spoke with him and explained that the Spaniards had come from heaven and were in search of gold.

He told the king that they were going to the island of Beneque where they had been led to believe there was much gold. The king wished them well and offered his help, but Columbus later wrote that when he told him that he served a higher king and queen in Spain, the king was under the impression that they were in heaven and not of this world. Columbus thought it best not to press this point. He writes later that the natives were so naïve and placid that they would be easy to subjugate and convert to Christianity, which was one of Isabel’s conditions for funding the voyage.

Now all he needed was the gold.

Some of his crewman were becoming fluent in the native language, and he sent them to trade with the Indians for their gold. They met with a man called Cacique, whom they took to be of some standing in the area. He was offered glass beads for a piece of beaten gold as large as a hand, and when they had agreed the deal, the Spaniards asked if he had any more gold. Cacique told them that he would return the next day with more of the metal. But the next day, instead of gold, Cacique brought 40 men, and put on a show of his displeasure. Columbus made signs to placate Cacique and finally the men that he had brought climbed into their canoe and left. After this strange turn of events Columbus felt that there was no more gold to be had on Española or Tortuga and decided to press on to Beneque. He had been told that the island was four days’ journey by canoe, which he estimated to be 30 or 40 leagues, a distance that his ships could cover in a single day with favourable winds.

However, the next day the wind was not very favourable at all, and either dropped or was against them. The ships were anchored some distance from the beach, and Columbus was still hoping that Cacique would bring more gold. He had sent some men inland to scout, and he was eating in the forecastle when they returned. The brought with them the king, who was carried on a litter and accompanied by around 200 villagers. The king came aboard, and when he saw that Columbus was eating, he promptly sat at the table with him and the Admiral offered him some of his food. Many of the villagers scrambled over the side and swarmed over the decks marvelling at the strange ship and its crew, who were becoming alarmed. When the king saw this, he ordered them all ashore again except for two older advisors who sat at the king’s feet. Columbus ordered food to be brought for them all. The king left just before nightfall and was carried in his litter up the beach into the forest.

Over the next few days, wind permitting, they sailed along the coast and wherever they stopped they were greeted by natives, who after initial trepidation, offered them food and gifts. There was little gold to trade, but whenever they could trade it for trinkets they did, and some of Columbus’ men were getting greedy. He ordered them to always give the natives good payment for their gold, after all, they were only giving them worthless trinkets. Word of the Spaniards love of gold had spread before them as they moved from bay to bay along the coast, and the natives came from further afield in their canoes and followed the ships. By now they had realised that the name Cacique meant king or dignitary, and was a title. By 24 December Columbus had been invited to meet other Caciques further along the coast, always with the promise of gold. Apart from the disappearance of the Pinta, things were going extremely well.