The novel "The ingenious nobleman Don Quijote de la Mancha", by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, begins by saying: "In a place of La Mancha, whose name I do not want to remember, It was not long since a nobleman lived………”. This ingenious but poor nobleman (a Duke) was called Alonso Quijano --but he was better known as "The gentleman of the sad figure"-- .

First part of the novel published in 1605

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

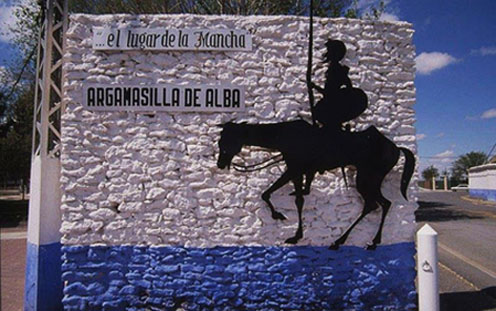

That place, whose name Miguel de Cervantes did not want to remember, was probably the village Argamasilla de Alba (Ciudad Real).

An aerial view of Argamasilla de Alba

The entrance to Argamasilla de Alba

Estatue of Miguel de Cervantes at the square Alonso Quijano

Another statue of Miguel de Cervantes in Argamasilla de Alba

But I would like to start this article saying: "In a place in La Mancha whose name I do want to remember ..., to continue with this article……”. But later I will say what that place is, that I have chosen.

Don Quijote (Alonso Quijano) toured other villages of La Mancha --now Comunidad de Castilla-La Mancha--, with his horse, "Rocinante", and with the squire Sancho Panza.

It seems that Miguel de Cervantes locates the origin of Don Quijote in Argamasilla, because Cervantes was a prisoner in La Cueva del Medrano, located in that area and that was where Cervantes began to write the novel.

"Don Quijote de la Mancha" is considered the first modern novel and the one that demystified the chivalrous and courtesan tradition.

Topics such as justice, freedom, love, kindness, idealism and social criticism characterise a story full of humor, satire and parody. Don Quijote describes his ideal, as a knight-errant, in one of the most well-known fragments of the work: "They are my laws, to undo wrongs, to lavish good and to avoid evil. I flee from the gift of life, from ambition and hypocrisy, and I seek the narrowest and most difficult path, for my own glory ".

From that moment, he called Don Quijote de la Mancha himself, baptises his horse as Rocinante and falled madly in love with Aldonza Lorenzo, whom he called Dulcinea del Toboso. He hired a squire, Sancho Panza, and begins his adventure trips driven by kindness and the desire to help the most disadvantaged.

Dulcinea del Toboso

Dulcinea and Don Quijote in El Toboso

Sancho Panza

The most famous scene of Don Quijote taked place in Campo de Montiel, where he fighted against giants that were only windmills.

Windmills in Campo de Montiel or Campo de Criptana

Alonso Quijano went crazy, reading several cavalry books.

Cervantes conceived this novel, in its most external aspect, as a tool to ridicule the books of chivalry, whose genre, already surpassed at the time in which the great Spanish novelist lived, provoked particular aesthetic preventions in the author, who saw such works as absurd, implausible and written with a false and unnecessarily bombastic style.

This didactic position justifies the cruel and burlesque attitude adopted by Cervantes, imposing the character, in such a way to its parodic function, that takes the hand of its own creator making him proud to have given life and not forgiving, in the second part, to Avellaneda, to have wanted to usurp his paternity. By portraying, in his madness, the old hero of knightly adventures that fails outside of his environment and his world, the deep Cervantes humor resolves the situation with a real tragic feeling, that pulsates imperiously under the comic clothes of the novel. Don Quijote is the prototype of the good and noble man, who wants to impose his ideal over the social conventions and the baseness of everyday life, acting as a human redeemer of a prosaic reality that hurts and offends him every day, establishing himself champion of the purest essences of love, honor and justice.

His own pilgrimage, through the dusty roads of the land of La Mancha, between innkeepers, muleteers and henchmen, struggling with hard and mean reality, contributes to his deep human sympathy, even with his ambiguities and extravagances. Alonso Quijano, converted by his dreams into Don Quijote de la Mancha, is first and foremost a man of flesh and blood, and thus, and precisely by virtue of his own humanity, he penetrates the world of the universal and the symbolic. He was a peasant nobleman.

The story of Alonso Quijano begins when he was 50 years old. He had a strong complexion. He remembered a girl from El Toboso, whom he automatically turned into his Dulcinea, or lady of her thoughts. His physical features and his hallucinated "sad figure", loaded with the old weapons that he carries on his bony limbs, surround him with an aura of heroism that irremediably overcomes the caricature.

This work is an ironic interpretation of the knightly world that Cervantes knew and loved. There were real cases of madness that could suggest, externally, the idea of the great protagonist of the novel. It has been thought of several characters named Quijada, such as Don Luis Quijada, secretary of Charles V and tutor of Don Juan de Austria, who had features curiously coincident with the Quijote, or a relative of the wife of Cervantes who carried that surname ; Zapata, in his Miscellany, talks about the case of a gentleman who went crazy and who wanted to imitate the adventures of Orlando, as in Don Quijote de Avellaneda, and whose insanity is explained as a hereditary tare.

Don Quijote, in his first outing, went alone against the world, although later his needed for a figure that at the same time serves as a contrast and lends him his brotherhood will be covered with Sancho Panza, who from chapter VII will be representative of the good sense, the claim to the things of the earth, and that if it ever stops the fantasy of its errant gentleman, others leave it more deeply abandoned to its first and infantile humanity. Since then, Don Quijote and Sancho remain united and opposed, brothers but at the same time hierarchically distinct, within the canons of baroque variety and chiaroscuro.

Don Quijote alone

Don Quijote and Sancho Panza

This union provokes a double current of mutual influences that perfects and civilises the union of the extreme figures that have best embodied the most unbridled pure idealism and the most sympathetically limited and domestic reality. Don Quijote radiates splendors of his greatness, in contrast to the technique of humor, from his first solitary departure through the fields of La Mancha, during the hard month of July, showing us the images of his investiture as a gentleman in the hostelry, between muleteers and lads of the party, and of the brutal beatings that he suffered from curious and arrogant people, rided on his dry and stylised Rocinante.

Here is Don Quijote, our brother and symbol of love and justice, who faces the eternal Spanish castles that are the windmills, consolidating one of the most ingrained literary myths. These images contrast later with his doctrinal spirit, when he speaks to the goatherds or when he projects his shadow of a mystic before the table of a hostelry, among soldiers, nobles and craftsmen, exposing, in the discourse of arms and letters, the theory of the two Spain of the sixteenth century, the two positions of Charles V's time: the inheritance of Don Juan de Austria, the hero of Lepanto, and that of the scholastic and theological bureaucracy of the bereaved Felipe II.

In the darkness of the night his figure stands out, among the torches of the adventure of the dead, suggested perhaps by the transfer to Castile of the corpse of San Juan de la Cruz. Thus approaches the divine madness of the greatest and most enlightened poet of the Spanish mystics with the human madness of the most just and chaste enamored with the knights. His figure oscillates between the pain of the sticks of the muleteers and the people of Segovia, the befas (rude derisions) of the superficial dukes and the victory over the Knight of the Mirrors, in the greenest and most flowery fields or in the double light of fiction and novel of the figures of Master Pedro's altarpiece.

In addition, he will leave the suffering rump of his good horse of flesh to ride Clavileño, which transports him in his fantasy, above the clouds and the stars, like a new Pegasus of the dreamer of the most beautiful illusions, just like also penetrates into the bowels of the earth to discover the crazy secrets of the novel of the cave of Montesinos, along with the obsession with the charm of Dulcinea. Precisely because he is a concrete man, both in his magisterial actions and in his grotesque aspects, Don Quijote can rise to the category of symbol and literary myth.

The personal aspects of Don Quijote appear, depending on the novel in which they find themselves, in different ways in its two parts. In the first, the episodes are combined that directly refer to the two central figures and that are largely the most famous, as a literary myth, of the whole work --windmills, flocks of sheep, adventure of the dead , conquest of the helmet of Mambrino, liberation of the galley slaves, diverse events in the hostelry, etc--, and then a great variety of subjects that are inserted indirectly and completely lateral and strange.

These episodes are but a summary of all the novel genres, that were fashionable: the pastoral, the Italian way of loving, the Moorish, the "exemplary novel", etc. In the second part, it will be Cervantes himself who tells us that the reader, undoubtedly with penetrating intuition, would prefer the feats and conversations of Don Quijote and his squire to other matters, hardly related to them, such as the intervention of the protagonists , for example, at Camacho's wedding, where he falls squarely in the same line of action.

Once reached the peak of maturity, the novelist enjoys presenting Don Quijote, both in triumphal episodes as in the victory over Samson Carrasco, under the guise of Knight of the Mirrors, or in the adventure of the carriage of the lions, as in the soft intimacy of the house of the Knight of the Green Overcoat, or when collecting the rebellion of the character before his false author Avellaneda. We can see how, towards the end of the novel, the "quijotism" is triumphing, in Sancho's way of being and in the immense network of adventures of the chapter of the dukes, where the chivalrous world prevails, in life and in feelings, with the simulation of taunt, with what constitutes a formidable staging of a whole society that enters into adventures and populates fields, castles and villages; of islands, cavalcades and fantastic and grotesque beings.

In addition, throughout the second part in general there is an evolution towards the sanity of Don Quijote, deviated by the own phantasmagoria, built on purpose in the episodes of the dukes. Once the protagonist has been defeated, in Barcelona, the novel ends with the pain of the worst defeat, suffered by the errant knight and his anguished return to his village, recovering his reason on his deathbed.

Between the first and second parts, that really wrote Cervantes, appeared the second volume of Ingenious nobleman Don Quijote ... of the lawyer Alonso Fernandez de Avellaneda. Cervantes was very upset with the usurpation and with the tone of disdain, employed by Avellaneda in his observations, and, in the prologue of his second part and in the final chapters, satirised very harshly the apocryphal author, who was hiding under a pseudonym.

Don Quijote de Avellaneda is a vulgar falsification of the fundamental conception of the novel, turning Don Quijote into a brutal and monomaniac character, lacking in flexibility and grace. His contemporaries only understood Don Quijote in its most superficial and comical aspect, although Romanticism, especially German, valued the type of Don Quijote interpreting it as a humanly melancholic character, with a deep philosophical content.

Well, as I said at the beginning, now I would like to say what is the place of La Mancha, which I want to remember. That place is in the outskirts of the village Madridejos (Toledo), because, a few weeks ago, a brother of mine sent me a photo, which he made, outside of Madridejos --specifically on Avenida de Europa, Kilometre 108--, where there is an industrial warehouse of the company MAYCOMETAL, SL, a company that manufactures metallic structures and, next to that warehouse, you can see a metal figure of Don Quijote and, very close to it, there is an old train locomotive. Then, when my brother saw that, he imagined Don Quijote fighting against the locomotive, instead of fighting against a windmill. You can see that image below:

Don Quijote and the locomotive

The map of Madridejos

An aerial view of Madridejos

At the entrance of Madridejos, you can see another image of Don Quijote.

Image of Don Quijote

And in the village, you can see the statues of Don Quijote and Sancho Panza.

Windmill in Madridejos

Well, I hope that you will like this article. Please tell me if you have ever read this novel.

Until my next post, kind regards,

Luis.

Sponsored by Costaluz Lawyers.

Please click below: